Welcome to THIS JUSTIN, a column dedicated to my love of all things weird and spooky. Each week I’ll be taking you on a deep dive into something creepy and/or crawly and talking your ear off about why I love it so much. Spoilers ahead, so heads up.

Childhood is a period fraught with fear. People tend to fear what they don’t understand, and children, not understanding as much as adults, tend to be afraid of more things. Usually, art that is produced for children tends not to be as dark or frightening as movies, books, and shows for adults. And on the rare occasion that it’s supposed to be “scary,” more often than not it’s just mildly spooky. But…there are times when children’s movies and books and TV shows hit a note of horror that is unique to that work and unlike anything else out there. In this series, I’ll explore some of the works of art that affected me as a child in the realm of horror.

Children’s movies are supposed to be fun and friendly and colorful and distracting. Usually, they’re geared entirely towards kids. “Fun for the whole family” typically means “your kids can watch this.” Sometimes there will actually be stuff the whole family can enjoy (I’m looking at you, Guardians Of The Galaxy) but the majority of the time, it’s for kids.

There was a strange phenomenon in the realm of children’s movies when I myself was a kid. For the sake of this article I’ll stay focused on the mid to late ‘80s when I was but a wee slip of a boy. Now, what I just said isn’t anything really groundbreaking. Films like Labyrinth, The Dark Crystal, The Never Ending Story, and the lesser known, but still horrifying, The Adventures Of Mark Twain segment “The Mysterious Stranger” are all known in my generation to be the stuff of nightmares. I normally detest “when I was your age”-ism, but I truly believe that the art directed at children of my generation was some of the most unintentionally horrific ever produced.

For me, the movie that best sums up that delicious mix of childhood nostalgia with gloriously terrifying nightmare-fuel is the Don Bluth classic, The Secret Of NIMH. As a child, I was obsessed with this film, and not just because I shared a name with one of the heroes. NIMH is an amazing story, and honestly still holds up when it comes to that storytelling aspect. It’s the tale of Ms. Brisby, a field mouse who must move her home before the plowing season begins but is unable to do so because her son Timothy is extremely sick with pneumonia. She enlists a whole host of characters to her help her out: Mr. Ages, a wise old mouse who was friends with her late husband Jonathan; Jeremy, a friendly but clumsy crow; Justin, captain of the guard for the rats who live in the rosebush; and Nicodemus, the wise and mysterious leader of the rats who was also friends with Jonathan Brisby. As the film progresses, we witness a power struggle for leadership of the rats as the villainous Jenner plots to wrest away leadership from Nicodemus. We learn that the rats being able to talk and plan and plot and use electricity and strategy isn’t merely a children’s cartoon device, but rather the result of the rats being experimented upon by the National Institute Of Mental Health (NIMH) which gave them drastically increased intelligence (although talking rats who can reason and use machinery isn’t really a huge change since mice and owls and crows can also talk and reason in this movie, but whatever). Cool, huh?

This plot summary alone is enough to make this film an exceptional children’s film, but it isn’t remembered just because of the quality story and sharp narrative. Rather, the elements of this film that stand out the most are the darker aspects that you wouldn’t normally find in a children’s animated feature.

For starters, the film makes it very clear that Timothy, Ms. Brisby’s ill son, will certainly die if they attempt to move him, while the whole family will perish if they don’t move due to the upcoming plow season. Even as a child without a grasp of the utilitarian dilemma of the Brisbys, I was still struck by the grave choice that Ms. Brisby faced: did she abandon her son for the sake of the rest of the family or did she risk his life by moving him? That was some heavy shit for a kid to think about. It’s also worth mentioning that Ms. Brisby was clearly struggling to hold it together since the loss of her husband. This combination of mortality and dealing with grief was an oddly mature theme for children’s film. Until that point most of the movies I’d watched that were geared towards my age group presented loss in terms such as “oh I hope we don’t lose the baseball game to the better team” or “I hope these rich assholes don’t take our houses and force us to move out of the neighborhood.” These were scary ideas to a kid for sure, but NIMH had the stuff to grab us by the collar and shove our faces right into the muck and mire of our own mortality. Timmy wasn’t going to lose to a neighborhood bully in a bike race, or not get to go to a dance with a girl or whatever. Timmy was going to die. To a child, this was a stark lesson.

It doesn’t stop there. In absolute terms, the film lays out the fate of the late Jonathan Brisby. He died while trying to poison Dragon, the monstrous tomcat that belonged to Farmer Fitzgibbons and also has it out for Jeremy the crow. Again: Jonathan Brisby, a field mouse, was killed and eaten while attempting to poison a cat. This wasn’t the goofy antics of Tom and Jerry, where we knew Jerry would outwit the bumbling Tom. This wasn’t Wile E Coyote, who couldn’t find his ass with both hands and a flashlight, dropping the ball again and again while trying to catch Roadrunner. This was a character in a children’s cartoon running a suicide mission, failing, and being eaten as a result. This isn’t the only depiction of death in the film involving Jonathan Brisby. We are mercifully spared the sight of his demise, but in learning of how he and the rats escaped the lab of NIMH we’re treated to a scene in which a handful of mice are “sucked down a dark air shaft to their deaths…all except two”: the cranky Mr. Ages and Jonathan himself. The scene of the mice dying isn’t quite gruesome, but there’s no doubt left as to how they end up. We see the struggling to hold on to the sides of an air shaft as they’re pulled into the dark squeaking and squealing in panic, and the camera angle moves in such a way that it lingers on their terrified faces for a beat too long.

Speaking of the NIMH lab, I bet you wouldn’t expect to see a rather surreal depiction of animal testing in a kid’s movie, but guess what? The Secret Of NIMH has one! In a somber flashback from the point of view of Nicodemus, we are treated to an origin story for the rats in the rosebush. Nicodemus, along with several other rats and mice (including Mr. Ages and Jonathan Brisby) were captured off the street by the scientists at NIMH and injected with an unspecified liquid. The scene is unsettling enough due to the depictions of monkeys, rabbits, and beagles all looking sad and scared in the lab, but it’s taken to all out Cronenberg territory when the rats are shown reacting to the injection. The music kicks into a frantic orchestral score as different color filters are flashed over the animation, all set to a shot of a rat doubling over and clutching it’s stomach as a pulsating red light (I’m assuming this signifies the injection site and the changing of the rat’s nature) grew in it’s torso. The next shot is of the rats falling down a weird Lovecraftian tunnel, filled with painted chromosomes and arcs of lightning to depict the psychedelic metamorphosis they’re going through. I remember watching that scene as a kid and being mystified and fascinated by it all. I honestly thought the rats were gaining superpowers. Decades later when I was watching it with an ex-girlfriend, she asked how my parents could let me watch that movie and I must admit I was at a loss for words. I mean, I guess I should be grateful because this film doubtlessly shaped my views on animal welfare as an adult, but did I need to see it at such a young age? Who knows?

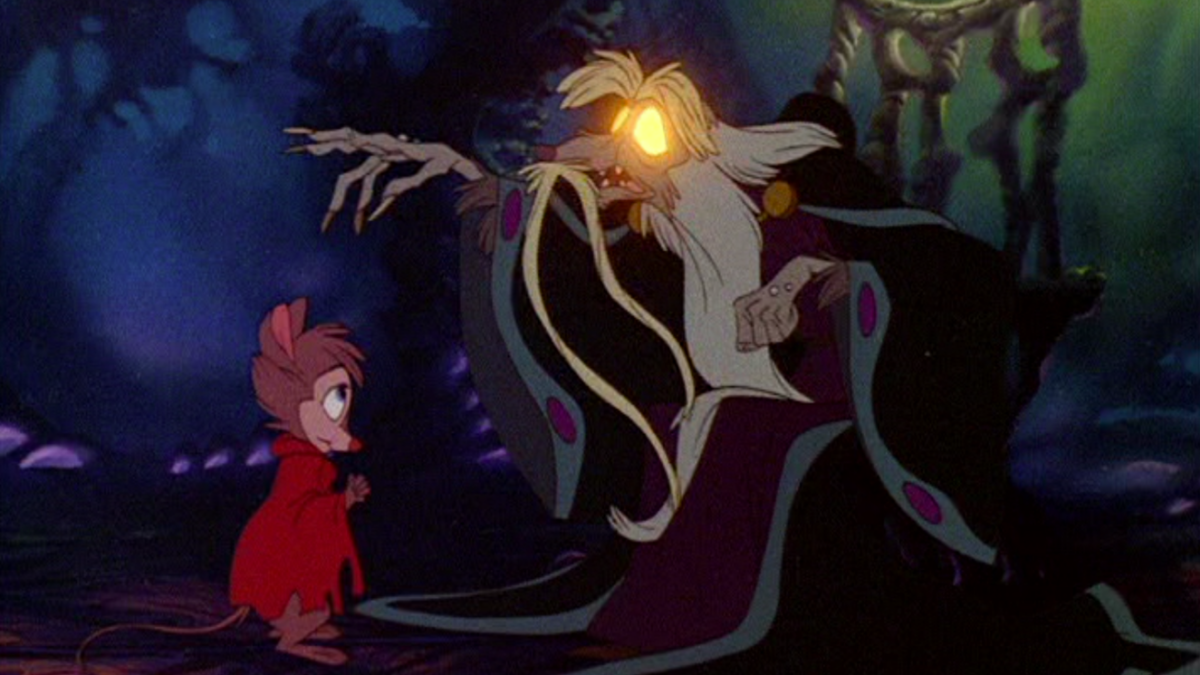

The character of the Great Owl, the oracle-like character that Ms. Brisby goes to for advice, is another universally feared character by people of my generation who saw this film. Despite being a good guy and showing Ms. Brisby respect, due to who her husband was (side note: everyone in this film loves reminding Ms. Brisby that her husband is dead), the Owl radiates an air of barely subdued menace. We first meet him after he summons Ms. Brisby into his lair, where she is nearly attacked by a (disturbingly realistic) spider. The spider, fangs quivering and dripping in anticipation, is crushed by the Owl, who opens his eyes to glare her from a face turned upside-down, because owls are weird like that. He then proceeds to stomp around his lair, terrifying Ms. Brisby. At one point, he begins flapping his wings and causes a shower of bones to fall from above onto her. Only as an adult did I make the connection that, given the diet of owls, she was being showered in the bones of other mice. He tells her he can’t help her and is ready to leave until he finds out her name, at which point he gets up in her face and speaks highly of her dead husband as we see her quivering reflection in his glowing eye. It’s a strange choice to make one of the good guys as baldly terrifying as the filmmakers decided to make the owl. One could argue that maybe his wisdom made him something transcendent of our conceptions of good and evil. Which would make sense if this wasn’t a fucking children’s film. Instead of making this ontological connection as a kid, I was mostly just unnerved by this strange mustached bird with a booming voice who just seemed annoyed at our protagonist and snapped at moths in mid-sentence.

The last part of this movie that left an impression on me as a kid was the climactic fight between the heroic and handsome Justin and the villainous, scheming Jenner. It begins when it’s revealed that Jenner has sabotaged the pulley system the rats were using to move Ms. Brisby’s house, causing it to fall and crush Nicodemus to death. When Ms. Brisby attempts to rally the rats to leave the thorn bush because the scientists from NIMH are on their way to recapture them, Jenner claims she is hysterical and attacks her with a sword. When his minion summons Justin to help, Jenner attacks the minion, mortally wounding him. Justin and Jenner then engage in a dramatic swordfight, with Jenner openly admitting he murdered Nicodemus before spouting off a Nietzschean line about taking what you want when you can. Justin bests him in combat, stabbing him through the stomach. Justin then turns to the rest of the rats, telling them that they will move to Thorn Valley. Jenner attempts to sneak up on him one last time when his minion Sullivan, not quite as dead as we thought, throws a dagger at him, hitting square in the back and killing him. Jenner falls to the mud snarling, and Sullivan slips away.

This scene is striking for several reasons. First, the Machiavellian machinations of Jenner are far more brutal than what is seen in children’s films. Not only that, but they’re weirdly isolationist and almost nationalistic. Jenner believes that the rats shouldn’t have to move, that the rose bush was their home, and he’s willing to kill for this belief. This motivation is above and beyond the typical megalomaniacal tendencies of your run-of-the-mill children’s film villain. He doesn’t kill Nicodemus simply because he wants power, he kills Nicodemus because he believes Nicodemus is incapable of leading the rats. It’s never stated outright in black and white terms, but it can be inferred that Jenner believes that killing Nicodemus is for the common good, and that only he has the will and the strength to follow through with what is necessary for the common good. This vaguely fascist glorification of “might makes right” seems more at home in a Frank Miller comic, but here we are with it in a cartoon about talking rats and wizard owls. The fight itself is violent and brutal, even more so than, say, the fight between Obi-Wan and Vader in A New Hope. Jenner is clearly trying to kill Justin, hacking viciously away at him every chance he gets. And when he takes a swing at his former minion Sullivan, we see blood. Same with when Justin gets cut on the arm, and same when Justin deals it back to Jenner. Blood. Actual crimson blood. Jenner’s facial expressions the whole time are monstrous as well. He’s not so much speaking his lines as he is barking and snarling them at Justin. There’s nothing smooth or suave or dignified or even remotely sane about him as a villain. He goes from placating demagogue to violent murderer at the drop of a hat.

The sequence ends with the rats frantically trying to raise the Brisby home, which has been steadily sinking into the mud the entire time. For some reason, her children are still inside and the rats are unable to stop it from sinking. Ms. Brisby uses a mystical stone given to her by Nicodemus, and her love for her children powers it, enabling her to raise the house from the mud. For the umpteenth time in the film, the stakes are life and death, although by now I guess we’re supposed to have gotten numb to it.

As I said in the beginning of this article, few things get under my skin like bullshit ageism directed at kids. When I see someone post something on Facebook about how when they were a kid they didn’t play on an iPad because they were too busy playing outside, I want to fucking scream. Kids don’t have it easy today. Not by a sight. We’re in the midst of a pandemic, climate change is an existential guillotine blade, and our geopolitical situation is as fucked as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs. But…kids today will probably never know the fear of watching Dragon sneak up on Jeremy with unholy bloody murder in it’s one good eye. They’ll probably never watch in dreaded anticipation as Ms. Brisby and Auntie Shrew frantically try to sabotage Farmer Fitzgibbon’s tractor before it lays waste to the Brisby homestead. And they’ll probably never watch the Brisby family mournfully watch as Ms. Brisby mixes up Timmy’s medication for him, worrying that he’s going to fucking die of pneumonia. And in a way, that’s a bummer, because this movie rules and I think I owe much of my current taste in film to being exposed to it at such a young age. I watched it recently and it still holds up, although I can’t say I’m the most unbiased of viewers. Either way, it’s is a classic example of how far children’s entertainment has come in the last forty years or so. So be thankful, youth of today: at least the heroes of your movies these days don’t have to worry about their child dying after their partner was violently murdered by a monster cat.