This is The Pasolini Project, a monthly discussion series from Adrianna Gober and Doug Tilley delving into a vast body of work that, until relatively recently, had not been widely available on home video: the films of director, poet, journalist, and philosopher, Pier Paolo Pasolini. We’ll be exploring Pasolini’s filmography in chronological order, taking occasional detours through his staggeringly extensive artistic efforts outside of film, as well as the work of his collaborators and other related media.

Part Five of our deep dive into all things Pasolini comes during Cine-Ween, and to mark the occasion, we’re putting on some headphones, turning the lights down low and turning the volume up on a couple of spooky songs inspired by Pasolini: “Ostia (The Death of Pasolini)” by Coil and “Farmer in the City (Remembering Pasolini)” by Scott Walker. For previous entries in the series, click here.

Doug Tilley: Maybe we should start by talking about why we’re doing some songs at this point, to contextualize it. I don’t want to make light of anything, because these are both very serious songs, but they’re also tonally appropriate for this season, right?

It actually might make sense for you to start that off, since you were the one who brought the songs forward. I had heard the Scott Walker song before, but…it’s interesting, I listened to it years ago, but I never really connected it with Pasolini in the context of the album, which of course, looking back now, is ridiculous. That’s obviously who it’s about, but it’s not something I had been aware of the first time I listened to it.

Adrianna Gober: Well, my thinking for covering these songs was pretty simple: every October here on Cinepunx, we celebrate something called “Cineween,” which is a month-long event where we try to post at least one horror-themed article a day, typically about movies. If not, then content that ties in thematically in some way to the horror/Halloween theme. The problem that arose for this column is that Pasolini doesn’t really have any films one could categorize as “horror,” except maybe Salo, and Salo is a movie we were already planning on discussing at a later date.

DT: And, honestly, a lot of the work that we’ve done about Pasolini seems to inevitably be pointing towards Salo, because it’s a natural…if not ending point, then a kind of culmination.

AG: Right. So it just didn’t feel right to do it for October, with still so much work of his left to cover. So, I just got to thinking, what could we do instead? And I immediately thought of these two songs by Coil and Scott Walker, because I’m a huge fan of Coil and I love Scott Walker, too. I thought it would be fun to change things up a bit and talk about music instead of film, because that’s more in my comfort zone. Not that I don’t enjoy discussing films, but my background is in music. I come from a family of musicians, I grew up inundated with music from birth, basically, and have been playing music for more than half my life. And so I wanted to seize the opportunity to talk about something music-related for a change.

DT: I think it’s really healthy to expand, because we’ve been focusing so much on Pasolini’s films, and of course Pasolini, as an artist, did not just focus on filmmaking; he did poetry, he did essays. I think it’s appropriate for us to move outside of —- well, in my case, outside of my own comfort zone, even though I am a big fan of music, and I think I have a fairly eclectic tastes. I don’t have a musical background in any way, but one of the nice things about Cinepunx as a website is that it really does allow us to fit this into it as well.

AG: Right. And also, these songs are kind of “spooky” in a sense, so I thought the choice of topic was fitting.

DT: They’re extremely spooky! [laughs]

AG: [laughs] I think both of these songs are achingly beautiful, actually.

DT: I mean, I think they are beautiful in their spookiness, if you can say that. But I also feel like the closer we’ve gotten to both the work and life of Pasolini, the more affecting I find both of these works. Particularly, I have to say, after watching Abel Ferrera’s Pasolini and seeing how the death of Pasolini was dramatized in that movie; very violent and very explicit. In some ways, I feel like both of these songs are a more appropriate and more affecting way of presenting it. I know that sounds kind of strange, but —-

AG: I don’t find it strange at all, it makes total sense to me. That’s really interesting.

DT: And when we eventually return to Ferrara’s film, I might be able to revisit that thought, but in some ways, this kind of captures a horror that the movie didn’t necessarily capture in as affecting a way.

THE SONGS

DT: This is going to be interesting. You have me at a bit of a disadvantage. My familiarity with Scott Walker is…pretty good. My familiarity with Coil is almost strictly with their abandoned Hellraiser soundtrack. [laughs] It’s amazing, and I prefer it to the one in the movie, but I don’t really know anything about them. I guess it’s not just one guy, it’s a band, but it’s….what is it?

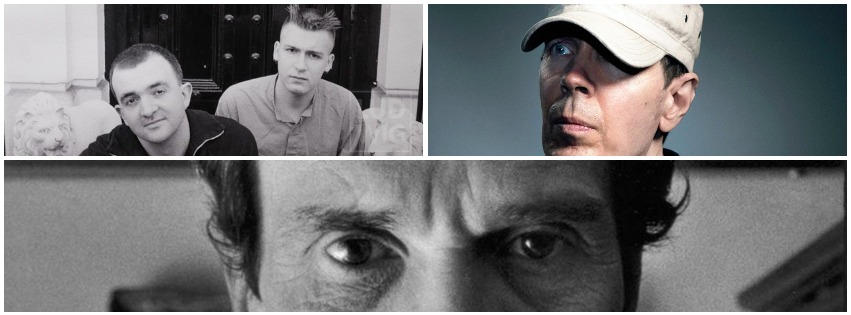

AG: It’s primarily two people: Peter Christopherson and John Balance. And they had a revolving door of musicians and other contributors join them for different albums and various side projects.

DT: One of them was from Psychic TV, is that right?

AG: Well, they were both involved with Psychic TV early on, though that didn’t last. How much time do you have? Because I can give you an in-depth history lesson on the genesis of industrial music.

DT: [laughs]

AG: In the interest of time and staying on topic, I’ll stick to Coil. Basically, Coil rose from the ashes of Throbbing Gristle. Peter Christopherson was a member of Throbbing Gristle, and when Throbbing Gristle disbanded in 1981, he and his then-boyfriend, Geoff Rushton —- who took the name John Balance — formed Coil. Shortly thereafter, Stephen Thrower joined, making it a trio. That’s the same Stephen Thrower, by the way, who wrote Nightmare USA and many other acclaimed film books. Anyway, after Stephen Thrower eventually left the group, Christopherson and Balance were cemented as the core members of Coil. They had their friends and peers join them in the studio for different albums, and there were some notable long-term contributors like Ossian Brown, Thighpaulsandra and Drew McDowall, but Christopherson and Balance were the central creative force behind Coil for most of its duration.

Coil.

It’s also important to note that Coil were practitioners of what you could call the esoteric, or hermetic traditions of the occult, basically. And a lot of their music was heavily informed by, among other things, the idea of sexual energy as a potent, transformative force, creating music as ritual magic as a means to channel that energy. Their debut E.P., How to Destroy Angels, for example, was designated as “music for the ritual accumulation of male sexual energy.” What that translated to, in sonic terms, is 16 or so minutes of bone-chilling, primal noise. Really exciting, mind-altering stuff for teenage me to discover.

DT: I can certainly see why, when we were talking about a topic that would be potentially Halloween themed in some way, that that you decided upon these two songs, because both of them are —- in slightly different ways —- pretty terrifying.

AG: Yeah, for sure. At any rate, I think that’s all you really need to know about Coil for the purposes of this discussion, in order to contextualize the song.

DT: I think there’s an obvious connection there with Pasolini, specifically his death. It’s interesting, because the element of darkness that’s in the Scott Walker song is right there on the surface, but there’s also kind of a romanticism to it. But with “Ostia (The Death of Pasolini),” it’s just….the music of the bones cracking —- it’s a very dark song, both in sound and in terms of lyrical content.

AG: Yeah, the lyrics to that song are very powerfully evocative; and not just the lyrics, but also some of the instrumentation. At one point towards, I think, the middle of the song, there’s this very jarring….I think it’s synthesized strings from a Fairlight, but it’s what sounds like very aggressive bowing of a stringed instrument that approximates the sound of screeching tires. It perfectly emphasizes the horror of what is being described in the song.

DT: So, maybe we should name the songs that we’re going to talk about here.

SONG 1: Coil, “Ostia (The Death of Pasolini)”

AG: Sure. The first song is “Ostia (The Death of Pasolini)” by Coil, from their second full-length album, Horse Rotorvator, released in 1986.

DT: So, obviously there’s a lot to unpack here. I think it makes sense for me to come at it from the perspective of someone who is less familiar with the song. I had never heard it before a couple of days ago, and the content of it…I found it a little difficult to unpack until I did a little bit more research on the subject. Obviously, I recognized that Ostia is the location where Pasolini was murdered, and I think anyone reading this probably already knows at least some of the context around that. The official story is that he was run over by a male prostitute, kind of repeatedly, and his body was burned afterwards.

AG: Yes, many of his bones as well as his testicles were crushed, and there was evidence that he was doused in gasoline and set on fire. It’s really horrifying.

DT: There is some controversy regarding the details around his death, and why he was killed. Specifically, whether the person who was accused and convicted of his death was actually the person who did it, because later in life, they said that they weren’t responsible for it. So there’s still a lot of mystery around that, to some extent, and I think to some extent that’s what both of these songs are tying into. Though this one, the Coil song, is very explicit about that murder.

AG: Yeah, definitely. And to your point about having difficulty interpreting some of the lyrics, I do think John Balance was being deliberately opaque to an extent with his writing. To me, this is a song that very directly comments on Pasolini’s death in certain respects, but also uses his death as a symbolic device, to allude to and comment on other things.

DT: I think that’s actually one of the things I had difficulty with upon my initial listens of it, specifically the reference to the White Cliffs of Dover, which I found a little —- not off putting, but a little confusing within the context of the song until I read further on it. And of course, the White Cliffs of Dover —- so many suicides occur at that location, and so it does fit thematically clearly within the rest of the song.

AG: Yes. And then there’s also the lines about the lion and the lamb, which is referencing a chapter of Judges. It’s the story of Samson killing the lion, and when he returns to the lion’s corpse later, he sees it’s rotting and that bees have colonized it and it’s oozing honey. Which is a very gross and very potent image. Within the context of the song, it obviously has some symbolic importance. I think that maybe it’s meant to draw a connective line between the lion’s corpse acting as sustenance or a life force for another entity —- nature taking its course —- and Pasolini’s death as a cosmic necessity, almost, to further some kind of cause, be it political or otherwise. There’s that line which repeats: “killed to keep the world turning.”

DT: Absolutely. It’s kind of a weird thing to talk about, as if his death was some sort of —- like you said —- cosmic necessity in order for us to progress, or the world or society to progress past the sort of controversial life that he led, and strictly and specifically, about how his homosexuality was treated at the time. I mean, for all intents and purposes, the general consensus I think is that Pasolini was murdered because he was so controversial, because he was someone who pushed a lot of buttons, whether it would be for his anti-fascism, or his homosexuality, or for the incendiary content of his movies. There were people who hated him and wanted him dead. And that’s the context, I think, of that “killed to keep the world turning,” right? Maybe a band like Coil couldn’t find a place for itself in the world without him being almost a martyr for that sort of controversial-ness.

AG: Yeah, I definitely think it’s fair to say that this song is positioning Pasolini as a kind of martyr figure. Switching gears just a little bit —- and maybe you disagree —- but I think there’s a sexual element to the song as well.

DT: Oh yes. I mean, those first lines…

AG: Yeah. The opening line is, “there’s honey in the hollows and the contours of the body,” which, on one level seems to be referencing, again, that story of Samson and the honey in the lion’s corpse, but on another level, it can easily be describing the flesh and curvature of a human body in a very suggestive way. And when you contextualize it against Coil’s work up to this point, I think it definitely has a broader application. My mind goes to the correlation between sex and death, especially as it relates to AIDS. I think the song is very much about or inspired by the circumstances of his Pasolini’s death, but is also using it to indirectly comment on the epidemic decimating so many people at the time. Because that’s an issue that the band was very passionate about.

To digress for a moment, honey is imagery the band had used before, in a music video they had released for their cover of “Tainted Love.” The video depicts a man dying in a hospice of sorts, from what, through various context clues, we can pick up on as AIDS-related illness. And the footage of the hospice is intercut with shots of Balance sitting at a table, dolefully intoning the words of the song while honey drizzles onto dead flies on the tabletop. So, the imagery of honey is something the band has employed before, and absolutely in a context where sex and death are closely associated. I don’t think it’s an accident that the same imagery is so pervasive in “Ostia.”

DT: And I guess in terms of those themes of sex and death, Pasolini’s death —- because it’s so enveloped with the fact that he was murdered by, potentially, a male prostitute, and because sex was such a part of his films, and part of his own death, it makes sense that this would be a figure that they would be interested in.

AG: Yeah, that was the connection I was trying to work towards, in my long-winded fashion.

DT: It’s a very haunting song, even without a lot of the context of the band and certainly —- you’re absolutely right —- I did not pick up on the potential references to AIDS, though obviously, that sort of love/death binary on display here is something that is hard not to notice. Whether it be the refrain of “killed to keep the world turning,” or the “throw his bones over the White Cliffs of Dover,” it is a song that seems to have almost a loving fascination with death.

AG: Yeah.

DT: And Pasolini’s death is one that I think spoke to a lot of people who felt in some way ostracized from society. Because, you know, he does make a pretty good martyr figure for a lifestyle that, certainly at the time the song came out, would have still been incredibly vilified. And you know, the Bible references here certainly fit in with the sort of biblical references we’ve seen in films we’ve covered up to this point.

AG: It’s funny just how simpatico it is when you think about it.

DT: Yeah. I always wonder, especially with these two songs….one of the reasons I was so interested in this project is that when I was becoming interested in cinema outside of horror and cult films when I was a teenager, Pasolini’s films were hard to see. They weren’t exactly the most available and accessible films, you know? And so I imagine, even in large, metropolitan areas where I did not grow up, that it wouldn’t have been easy to see a lot of his films. Obviously, with whatever was available to the writers of these songs that we’re talking about, he was still able to have a pretty significant impact. But I wonder how much exposure they actually had to all of his work.

AG: Yeah, I don’t know. I can only speculate about that. I think part of it might be that his films screened more in Europe than they did in North America, especially, you know, in the ‘70s or earlier.

DT: And it’s notable that the musicians we’re talking about here —- even though Scott Walker was born in the U.S. —- he basically lived the majority of his life in the UK.

AG: Yes, and much of his success has has been in the U.K.

DT: I guess that makes a pretty decent transition! Is there anything left that you’d like to talk about in regards to “Ostia”?

AG: Well, it would be nice to spend just a little bit of time discussing the musicality of the song.

Right off the bat, it establishes mood and atmosphere so well, because it opens with these sort of nature sounds, like crickets chirping, and other sounds you might hear at night in Ostia if you were walking near where Pasolini was killed. And from there, what sounds like a guitar or maybe a dulcimer enters, tapping out a haunting, arpeggiated motif that repeats over and over for the duration of the song. It’s entrancing, especially after the vocals come in. I really love Balance’s vocals; he had a very deep, sonorous voice and lends the song so much presence. And, again, I have to mention the screeching strings. It’s just very effective, very unsettling. Yet, there’s a beauty to the song as well, and I think it comes from something you already touched on, Doug, which is that these musicians are very clearly moved by Pasolini’s life and story, and that comes through. The song carries such a profound melancholy, almost in mourning, but it’s also full of a dark, carnal energy.

DT: It’s a song I’ve been returning to a lot over the last couple of days.

AG: That makes me happy!

DT: It really resonated with me and again, part of that is because it’s about a topic that I have a specific curiosity about, but it’s also a lengthy song. It’s, what, six and a half minutes long? Both of the songs we’re talking about our lengthy, but I feel like it really takes advantage of that ability to stretch out a little. The thing with Scott Walker’s music —- which we’ll get to in a little bit —- is that a lot of his songs tend to be a little longer, because the way he sings tends to stretch things out naturally.

AG: [laughs] I know what you mean. We’ll get into his voice.

DT: But here there’s a sort of soundscape on display that is a little bit more evocative in terms of the mood that it’s trying to present, and also with the imagery —- you’re right —- whether it be the tires, whether it be the sound that you might have heard on that beach where Pasolini was murdered. I mean, it all comes through. In some ways, it’s very cinematic. You can kind of see why a filmmaker might turn to Coil as a band to score a film, even if that [Hellraiser score] did not come to pass. You can see how that imagery does come through in the music itself, even outside the lyrics.

AG: Yeah, totally. The music and the lyrics work in tandem together to create a very complete picture.

DT: Most definitely. It’s a great song. It is haunting, though in this case, I found it like that kind of bittersweet haunting, compared to what we’re going to talk about next with Scott Walker’s “Farmer in the City.”

SONG 2: SCOTT WALKER, “FARMER IN THE CITY (REMEMBERING PASOLINI)”

AG: Do you want to talk about Scott Walker a little bit before we get into the song?

DT: Yeah, I mean, I think it makes sense to at least provide a little bit of context for him as an artist. It’s funny, because when I was getting into more interesting music, let’s say, when I was in my late teens and early 20s, Scott Walker at that time was a name I heard all the time because he —- I don’t like using the word comeback, because that’s not really what it’s all about. His rediscovery by a generation in the ‘90s and 2000s had already occurred by the time I was getting into his music. But the story of his life, how he had a certain level of pop success in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, and then less and less mainstream success as his music got more and more avant-garde and interesting and strange, and then kind of was rediscovered by another generation in the ‘90s —- I think it’s a really interesting [story]. It makes him a unique figure, and that voice is such a singular voice. I know I already referred to it a little bit, but that baritone…

AG: Oh yeah.

DT: The music that we have on display here in this release, which I think is from 1995 —- it’s on his album Tilt —- it doesn’t sound like the music of 1995. It sounds timeless, in a very kind of specific way.

AG: Yeah, it’s out of time.

DT: That’s exactly right. And that’s what I like most about his music generally, that it feels like…you know how some people say with psychedelic music and other avant-garde music that it feels like it’s from a different planet? This one doesn’t feel like it’s from a different planet, it feels like it’s from Earth. It just feels like it could have been recorded 50 years ago, or 10 years ago, or 10 years from now. It just doesn’t matter. It feels like something that is separate from the kind of music that is generally being made right now.

Scott Walker.

AG: Yeah, totally. And it’s interesting, because people talk about his career trajectory as unexpected, but to me it’s not unexpected at all. From the jump, he was a very reluctant star. He was not interested in being a pop star, he was interested in the avant-garde and the dark and taboo spaces in culture. And I think some of the most exciting work from the Walker Brothers was when they let Scott take over and get weird with it. Have you heard “The Electrician”?

DT: I have.

AG: That song is so good. But you can hear what he’s doing with Tilt, or later with Bish Bosch, for example, and trace it back to a song like “The Electrician” and Walker’s contributions on Nite Flights. It all shares DNA.

DT: What I really like about his music is how it’s very much a Trojan horse of weirdness. It’s packaged in this accessible way. This song is a really good example, right? It’s highly orchestrated, very kind of beautiful and in some ways romantic, if you weren’t really paying too much attention. But even when you know a lot about it, there’s an element of romance to it where you could see — I could see my mother listening to this and being like, “why don’t you listen to more music like this?” But inside of it, it has all these —- I mean, the lyrics of the song are so strange, and so eerie in a lot of ways. I find the parts of the lyrics that I cannot unpack to be more affecting and almost frightening than the stuff I can kind of piece together into what its meaning might be. And that really plays into the chorus of, “do I hear 21, 21, 21,” which I have to be honest, I don’t know what that is referring to specifically.

AG: I don’t know with 100% certainty what it’s referring to, either, because Scott Walker is usually very reticent to discuss the meanings of songs in any detail, but I do have my own interpretation. When I first heard the song, my immediate reaction was like yours; I didn’t really know what it was getting at with those opening lines. But then I started to think about it more, and I thought, “oh, it sounds like an auctioneer.”

DT: Yes, absolutely.

AG: So, if you think about the circumstances of Pasolini’s death, then those lines could very well be alluding to a transaction. Specifically one of a sexual nature. I’m thinking also of lyrics that come later: “can’t buy a man” and so on.

DT: I mean, that is as close to an interpretation of those lines that makes any sort of sense that I can really pull out. There are some lyrics in this song that I find really difficult, like the line that goes: “I can’t go buy a man with brain grass, go by his long, long, eye gas.” Which, again, the imagery of these lines creates all sorts of different emotions, and it creates all sorts of different visions in my own brain. But I think one of the things that I both like and find worthy of coming back to in regards to this song, is that some of these lyrics are so difficult for me personally to parse. I don’t understand, necessarily, how it all hangs together. That said, there’s a clear mood that’s being expressed here, and that comes through loud and clear.

AG: Yeah, for sure. And in that respect, the song almost reminds me of a tone poem. And I suppose in a sense it is; Walker’s text borrows quite a bit from an actual poem written by Pasolini.

DT: Now, do you want to describe the music? I know I already mentioned that it’s kind of orchestrated, that the strings are very much in front here.

AG: Well, arguably his voice is the central instrument. It carries the song to a large extent, and really kind of steers its dynamics. And this vocal track is atop a very moody string arrangement and aided slightly by some warm synthesizer textures. All together, it has a very unsettling effect. It’s eerie, and suffused with a mournful, nostalgic yearning, but it’s also kind of beautiful. Even the bizarre, inscrutable lyrical imagery taps into this sort of unconscious place where it resonates emotionally, even though the actual meaning of the words isn’t clear.

DT: Let’s go back to specific references to Pasolini, because after that intro, which —-the auctioneer makes total sense. You can definitely pull that into it. There’s a reference to Ostia, obviously where Pasolini was murdered, and then the lyrics of the song specifically quote a poem that Pasolini wrote to Ninetto Davoli, called “Uno dei Tanti Epiloghi” or “One of the Many Epilogs.” This is a poem that Pasolini wrote to Ninetto about their relationship, and when you read the translated version, it’s a poem about this dream he had about them together, and it’s kind of sweet and romantic. It’s interesting to have those those cited passages in this song which is so dark. This is the one that you can’t mistake the mood for anything but being kind of dark and distressing.

Pasolini with Ninetto Davoli.

AG: I don’t know whether you got this impression, but to me it seems as though this song is potentially sung from the perspective of Pasolini as he’s reflecting on his life, maybe even as he’s dying. Sort of like one last missive to Ninetto, or to the world.

DT: It’s an interesting way of writing about a figure that you have some interest in. And I think Walker probably felt a connection with Pasolini. I don’t know what the extent of that connection was, necessarily, but you know, they both came from small towns and they went out and explored the world and became interested in all sorts of different experiences. And there’s obviously enough of a fascination with Pasolini to want to envelop that person. But, you know, it could also come down to just being fascinated by his death. Many people, when they think about Pasolini, his death is usually the first thing they’re thinking about if they’re not thinking about one of his specific films.

AG: Yeah, for sure. Pasolini is a revered filmmaker, and his film work hasn’t been forgotten. But in a strange way, I do think he is an example of something that often happens, which is that the eventual fate of a famous person eclipses their achievements in some way. Outside of cinephile circles, I think it’s probably fair to say that for many segments of the population, if they’ve heard of Pasolini, they know him as either the guy who made the shit-eating movie, or the gay artist who died horrifically.

DT: Yeah. Certainly when I was really getting into international art cinema, when you heard Pasolini’s name and it wasn’t referring to his death, the movie they were referring was Salo. That was the movie that people referred to, and it took me years before I really expanded outside of that. Maybe it’s because the circles I ran in were very cult and horror based, and that’s the kind of movie that appeals to those kinds of people. But I also feel like it’s probably only been in the last decade where the availability of a lot of his catalog has led to a wider appreciation for his work. So, the fact that you have these musicians in the ‘80s who were showing their appreciation, and even in 1995 [with Walker]. These are people who are obviously appreciative of Pasolini as an artist, as a provocateur, and as a figure with a tragic end.

AG: Yeah, absolutely.

DT: This might be a strange question: which of these two songs do you prefer?

AG: That’s hard for me to say because they’re very different songs, and I don’t really consider one better than the other. I do have more of an affinity and affection for Coil than I do Scott Walker, although I really love Scott Walker. I just have more of a personal connection to Coil’s music, and this song in particular. So I suppose “Ostia.”

DT: They’re both, in some ways, moving songs. It’s weird to use the word “moving” in regards to songs that are evocative of a very dark and scary atmosphere, but you know, these are both songs that are…. there’s an edge of something romantic with both of them. And I think that speaks a lot to the way the Pasolini lived his life, and the way he expressed himself through his art, where that even when he was reaching his darkest places, he’s still sort of a romantic figure. And even though it’s awful how he died, there’s also something a little appropriate about it in the context of his life.

I’m really glad that we were able to talk about these songs. Even though the idea of this project was always to move outside the films of Pasolini, this was a really unique experience for me to be able to talk about these songs, so I want to thank you for bringing both of them to my attention. I hope that whatever people get out of our conversation about it, that they’ll at least listen to both of them and try to kind of gain a similar appreciation. This is Pasolini as an artist, we’ve talked about his work in the beginning of his career and we’re moving into the middle part of some of his work, but his long-lasting influence and the art that was created from his memory is something that we haven’t really talked about. So it’s nice to kind of be able to dive into that a little bit.

AG: And having a discussion like this also demonstrates the wide-ranging influence he’s had on other artists and creatives. Of course he’s influenced filmmakers, but it’s important to acknowledge that his influence extends beyond the medium of film to all sorts of creative people who saw something in Pasolini they could identify with or hold on to.

DT: We should mention, by the way, that these are not the only songs that mention or have references to Pasolini and his work. There is a world of them out there. These were specifically chosen because of the season, because of the Cine-Ween theme here on Cinepunx. But hopefully we can return to some more music, or maybe different forms of art inspired by Pasolini, in the future.