When we think of horror movie scores, we usually think of the same thing the “reet reet reet” of Mrs. Bates’s knife from Psycho or the slowed-down version of the same thing, “duna duna duna” from Jaws. And that’s because they represent two sides of the horror score: the build up and the break. Each part is just as important, and they more or less defined the way we gauge a successful score.

Where and how a director or music director implements their soundtrack has a great impact on how the audience digests the information. A type of Mickey Mousing shriek that carries the Psycho score helps to intensify the moment of impact, seeming to provide an other-worldly or emotional weight to what we’re seeing, especially considering the era in which it was released didn’t have the option of showing every puncture. Those things needed to be implied.

The same is true, actually, for its counterpoint Jaws, which has more gore, but almost always uses the tension of its score to build rather than show what’s happening. Take the key moment where the shark stalks the little boy, Alex Kitner, in one of the film’s most terrifying scenes. The shark’s POV and soundtrack carries the predatory movements of the shark and the scene, but that’s only released with the sight of a yellow pool raft capsizing. Silence and distance releases the tension, replacing what could be a bloody exclamation point with a quiet period.

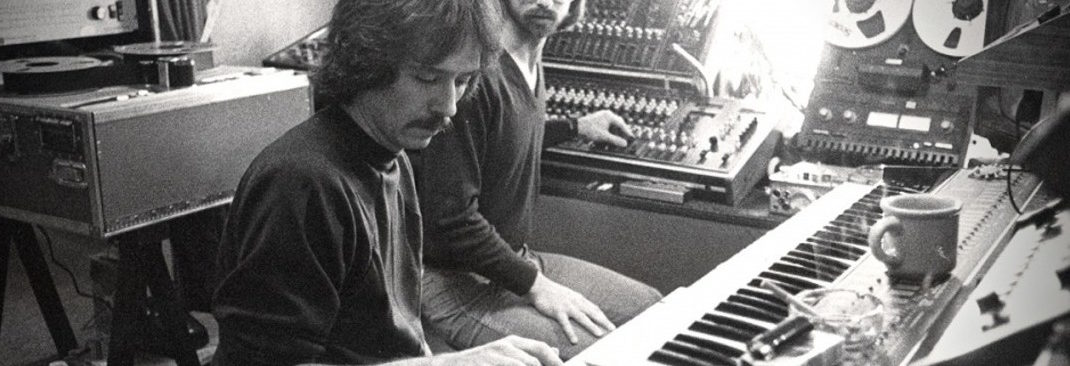

This is an idea that John Carpenter used to great effect on four years later in Halloween. Oft-considered one of the greatest and most influential horror movie scores, Halloween’s propulsive piano keys seems to act more as a cloud of dread over the town of Haddonfield, a reminder that something ominous lurks in the bushes and backyards of this Illinois suburban dream.

But like Spielberg, Carpenter doesn’t let his soundtrack over take the moment of impact. While the crushing impact of his piano seems to stone each scene with menace, his scenes of violence are typically silent, using the sounds of life leaving Meyers’s victims than the double-timed waltz of his theme. It’s fitting that the sound most commonly heard in these scenes could be best described as a balloon being deflated—though louder and inherently more terrifying.

These three films seemed to define the next two decades of horror movie soundtracks. Much in the way Phantom of the Opera and Noserfatu’s live-accompaniments created a template for the organ-laden symphonies of the black-and-white horror films between the 20s and the 50s, the ideas presented in films like Psycho, Jaws, and Halloween impacted the use of music in other blockbuster horror movies. There are others too, such as Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Exorcist, which put ambient noise and unconventional instrumentation at the forefront, creating a feeling of otherworldliness present in the film’s atmosphere.

But in the 2000s, as gore became so explicit in not just exploitation films but Hollywood box office juggernauts, original scores seemed to take a backseat. The 2000s were marked by a series of horror films that opted for nu-metal infused soundtracks to provide the backbone of their films, assuming that the Hot Topic shoppers that went to see these movies would want delight in hearing their favorite songs played over some teenager being mauled to death. The dominance of the Saw series throughout the 2000s is one of the most egregious use of soundtracks, which is almost meant to have the audience enjoy the grisliness of the crimes rather than be scared of them; no surprise that that was always a common criticism of the films. However, it’s use of soundtrack reinforces the idea that the film expects you to be on the villain’s side, not to question why audiences like this stuff, but rather just to keep them smiling.

Film’s got louder in soundtrack and sound effect, particularly in an era when remakes dominate the horror landscape. Rob Zombie’s Halloween, set to both the face palming, on-the-nose music of the 70s and explosive sounds of his professional wrestler version of Meyers walking through walls, indicated a change in the guard.

It wasn’t until a few years later where films like It Follows learned how to use volume and repetition as signals of dread, rather than to punctuate a jump scare. This a film about horror lurking at every corner and in every person; so, it only makes sense that the score starts at unexpected times. Disasterpeace’s dubstep rises and falls with the tension, evoking some of the horror’s past and present, but dispatching these things in tandem and at a moment’s notice. It’s what keeps the film so terrifying throughout its run time. It becomes an aural metaphor for the monster.

This brings us to It, the biggest horror movie of all time. The film’s influence will outsized the actual strength of the film, as its box office has. But while the film has a wealth of positive attributes, including casting and production design, It’s soundtrack tends to work against the movie’s best impulses. Take for instance the moment when Richie wanders into the clown room. We know something is going to happen here. There’s so much tension on display that it can’t not be relieved at some point, one of these clowns has to be Pennywise. But defying logic, the beat to scare the audience comes just slightly before anything scary happens, selling out the film’s surprise. And that’s where problems with horror scores can come it because they’re all about releasing the tension. It’s a valve that needs to be loosened, but it has to be done at the right time.

However, when you’re operating at such high volumes, as It tends to do, heightening even more can be a difficult prospect. It tends to work on a more-is-more modus operandi. The more creepy images, the weirder Pennywise, the more childlike the kids, the scarier it is. It would only make sense, then, the louder and more intense the soundtrack, the more effective. However, It misses a crucial element, gone from a lot of subpar horror films: rhythm.

Soundtracks are about rhythm. How they care the film and when is a huge part of knowing when to scare the audience. It’s when Bernard Hermann’s score doesn’t kick in until the moment that Janet Leigh sees Norman Bates or when Carpenter’s score drops out right at the moment of impact: knowing when to implement the score is as important as having the right one.

In essence, the score must work in tandem with the rest of the film, serving to keep the tension up even when nothing is happening. The score is a shadow and specter of danger, not the whole thing. And when the movie becomes more about volume than rhythm, the whole thing can fall apart. These scores have to work as an extension of the monster, cuing and overwhelming the audience on a beat; not distracting them to the fact that they’re just watching a movie.