On occasion you might see me contesting—frequently, with genuine conviction, and no trace of irony—that Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger is something of a cinematic masterpiece—one of the greats of the 21st century. Such a view is not popular.

Upon release the film was, as is well known, widely panned for its length, casting, tonal shifts, narrative content, and budget. Of these criticisms, only one can be regarded as anything but obscurantist nonsense: casting. This criticism is undeniably a site of contradiction when contrasted with what I will say regarding the content of the movie—as I hold that The Lone Ranger is one of the clearest anti-capitalist, if not Leftist, works of cinema to have received release in recent years. (You might now be thinking of further contradictions that possibly abound here (“Anti-capitalist? It had an astronomical budget!” Just hold up a sec!—I’ll discuss them later.)

To comment on the fickle, vapid criticisms of length and budget, I note the view of Devin Faraci, who—in commenting on the meltdown of Disney’s other financial failure, John Carter, and the relationship between industry reporting and production companies—observes that “90% of the industry reporters […] take their stories directly from marketing and executives… Hollywood industry reporting always, always, always sides with the executives because numbers are quantifiable…”

We’re dealing with nothing different in the case of The Lone Ranger (TLR)—it’s easy to interpret the high numbers attached to the movie as a rationalisation for why it was clearly a failure. However, TLR also had the disadvantage of being—compared to a wrongly shit-upon space adventure movie—a profoundly ideologically pointed revision of what America knows as history, which aimed to explore the violence that founded it as a country.

One can only imagine, with subject matter such as this, the profound risk the Disney executives felt they had created in TLR, upon seeing what the creative team of the Pirates franchise had turned in. The American public would not be open to this: a movie that presents for all to see the depravity of how the West was won and the destruction unleashed by White Americans in their expansion. Given its problems, and given its content, was TLR going to be anything other than buried?

The Lone Ranger is Verbinski at his political clearest. Yet, how is one to build a franchise upon a movie that cannot do anything but straddle tragedy, offers but the slimmest catharsis, and decimates liberal ideology through showing us its brutality? Is it a surprise that liberal, White American reviewers reacted as they did?

Yet, with this cursory assessment in mind, recourse to the most banal and flatfooted of criticisms and primers for criticism, regarding length and cost etc., become predictable and expected—and, in my mind, untenable. What TLR attempts to do and the truth it desires to tell foreclosed its success.

With the above in mind, let’s dive in: The Lone Ranger, a masterpiece, “Conceivably Leftist Cinema”. The former claim I won’t substantiate, as I will not discuss performances, influences, direction, etc.—though there are places where you should do that.

I will explain, or at least sum up, the latter claim by interpreting and discussing the thematic content of the movie in terms of Leftist ideas: specifically anti-Liberal, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist notions that foreground the position of the oppressed in this tale.

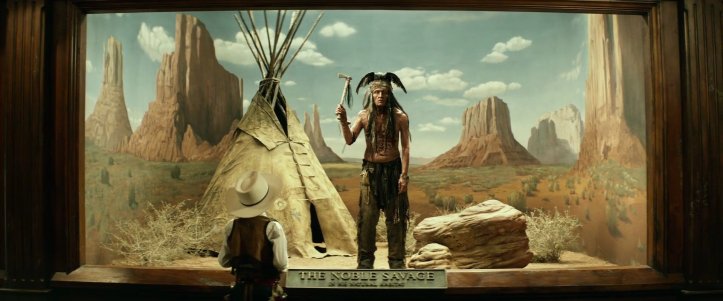

- The story of the oppressed:The Lone Ranger opens and organizes itself around that final point: the oppressed and their story—which is to say, Tonto (Johnny Depp). Verbinski, as he is wont to do, tells the tales of underdogs and seeming fools, and in this case he has TLR narrated by and framed around the perspective of a Native American made mentally ill by White violence and society. This madness is the condition for the historical revision advanced in the storytelling—we simply cannot be sure what is real, what is heightened, what is fake. TLR takes up this madness and exhibits it, from the peculiarities of seeing a horse in a tree to cannibal rabbits—are we sure this is really as it was?—to elements and objects from the time of the elderly Tonto’s narration entering into and being used in the story (e.g. peanuts in grave).Some, for example Richard Corliss, seemed frustrated that the Ranger is presented as a “well-meaning oaf,” “Tonto’s stooge,” and unaware “that the Lone Ranger is supposed to have a partner.” Corliss misses that these are a feature and not a bug of the movie. Given the historical attitude of the white man, his arrogance, his need to civilise, is there another way such a man would behave or another role he should occupy? This is an attempt to decentre whiteness (even as it somewhat underlines it), much in the way Mad Max: Fury Road tried to decentre the male.

This is the story of a casualty of liberal, capitalist violence.Tonto’s isa madness born of being stripped of identity and place. Nearly everyone endangers his life or seeks to put him away, on the sole condition that wrong life cannot be lived rightly. Yet, the film gestures that lines of connection can be made: where the bumbling White oaf goes under and accepts the logic, story, and warnings (“never take off the mask”) of the oppressed, solidarity is possible. This is a shaky solidarity that always courts, as much as it threatens, a loss of, privilege. The danger of this loss, the story asks us to recognise, is a matter of justice and the need to find new grounds for it.

This is the story of a casualty of liberal, capitalist violence.Tonto’s isa madness born of being stripped of identity and place. Nearly everyone endangers his life or seeks to put him away, on the sole condition that wrong life cannot be lived rightly. Yet, the film gestures that lines of connection can be made: where the bumbling White oaf goes under and accepts the logic, story, and warnings (“never take off the mask”) of the oppressed, solidarity is possible. This is a shaky solidarity that always courts, as much as it threatens, a loss of, privilege. The danger of this loss, the story asks us to recognise, is a matter of justice and the need to find new grounds for it. - Anti-liberalism:

To begin where this movie starts is to find oneself on a train, a train that is a metaphor for liberal progress. This train weds liberalism with capitalist expansion, even as it houses religion and secularism. It houses the latter two by having a Christian woman ask John Reid (Arnie Hammer) if he will join her group in prayer. He won’t. Reid has his own “Bible”: John “father of liberalism” Locke’s Two Treatises of Government. However, this is a movie told by and for the oppressed—by those oppressed by this liberal order—and as such TLR is about a loss of faith in this “Bible” of liberal secularism.As we proceed we are brought to see that liberalism is deeply interconnected to the ever-germane fascism within the ideology: genocide, capital, and military imperialism. The Ranger is shown and encounters all of this through Tonto, who knows it all too well and who shows the Ranger the consequences of this for the wider world. We see that the rhetoric of equality, property rights, and freedom soon reaches its highly racialised limit. Just as liberal notions of equality and freedom were a specifically white freedom—and a profoundly bourgeois white freedom at that—so notions of property were similarly racialised—as witnessed in the extermination ofthe natives for their land and resources. Liberalism is imperialism, is fascism, is capitalism, is Whiteness, is terrorism. Insofar as Locke also forms the grounds for John Reid’s position as a lawyer, TLR also charts his becoming outlaw—or again, his losing faith—as he discovers not just the insufficiency of this White law to bring justice to the oppressed, but that Cavendish (William Fichtner) and his bandits do not simply represent organised crime at the edges of the liberal-capitalist system, but that this system itself is organised crime. TLR charts the vacuity of the White liberal order and the need to stand outside of it.

Insofar as Locke also forms the grounds for John Reid’s position as a lawyer, TLR also charts his becoming outlaw—or again, his losing faith—as he discovers not just the insufficiency of this White law to bring justice to the oppressed, but that Cavendish (William Fichtner) and his bandits do not simply represent organised crime at the edges of the liberal-capitalist system, but that this system itself is organised crime. TLR charts the vacuity of the White liberal order and the need to stand outside of it. - Anti-capitalism:Having noted the imbrication of liberalism with capitalism thatTLR notes, we should spend a little time thinking about the consequences of capitalism (or really the proto-capitalist capture and seizure of resources) upon the world of the movie.Most clearly we are presented with the grotesque imbalance this White liberal-capitalist order has realised. The imbalance of man (Cavendish’s cannibalism, the symbolic face and truth of the capitalist underbelly) leads to a profound ecological imbalance (rabbit cannibalism), rooted as it is in the fetishisation, idealisation, and capture of the money form (silver) that provides the basis for capitalist expansionism and entropy. The world eats itself.Further, we can relate Tonto’s story to this anti-capitalist thrust in seeing that the societal and ecological imbalance and disturbance threatened by the white man’s progress are not localised to one human wendigo; but that the train sequences that bookend the movie frame the liberal-capitalist notion of progress—and specifically the force of this progress itself—as the wendigo. This progress imbalances, the expansion closes down, this movement is entropy. Tonto seems to comprehend this when he says Cole (Tom Wilkinson) is just another “stupid White man”, leaving the corrupting force of the train-progress itself to be destroyed.In a very timely move, we are also faced in TLR with the desire of corporations and businessmen to buy their country. Cole wants to connect and make a country. Class struggle and oppression are the basis of this goal. Signalling melancholia, the film opens at close—progress would not be stopped, just delayed. We have to acknowledge that the problems of capitalism and liberalism that we see today are constitutive, features not bugs; they have a bloody history and on this train the imbalances and entropy only increase.

It is quite clear to me that The Lone Ranger is an extraordinary achievement. It is a tight, rich, dense, propulsive work of storytelling and symbolism. That it got made is beyond my comprehension. It is blockbuster art of the highest order—from its sumptuous visuals and action set pieces, to its story and content; this is a dense and daring movie that deserved so much more than it received.

Yet, as I acknowledged earlier, it is not without its problems. The casting of Depp was rightly criticised for the use of red face and perpetuating a lack of representation. It was brutally misguided and shows that, on a systemic level, the kinds of racism and oppression the movie highlights and criticises were active in its production. I fully believe this movie is important, and the thematic content speaks clearly on many vital issues. Seriously, I can think of no movie that has taken a stance like this on anything I noted above—but I cannot pretend the casting was not an affront. The movie will always be bracketed with that truth. Even recognising the reality of “No Depp, no movie” only presents us with a reiteration of white supremacy and the complicity of “capitalist radicalism”. All there is to say is that, given this problem, we are at the very least faced with a movie that forces Tonto out of what he has narrated.

Additionally, if you feel there is a contradiction between a thematically anti-capitalist movie being made within a capitalist system, perhaps we should be careful about where we place the burden of criticism. It can hardly be on the anti-capitalist themes or those who espouse them. Criticism, in my mind, is to be directed against the capitalist edifice. Anti-capitalist themes are rich and important; the problem is their monetisation and ironisation in a capitalist economy. The questions for Leftist cinema would include who owns the means of cinematic production, whether the industry is nationalised or privatised, how wealth is distributed. Yet, movies are not made in hypothetical economies; blockbusters are made in Hollywood’s—a capitalist one. Anti-capitalist ideas deserve to be in cinema. Our criticism should be aimed at the capitalist system that produces them, and its history of violence and the limits it reaches in showcasing these ideas.

The Lone Ranger is ultimately a demonstration of this limit: the limit of radicalism in capitalist cinema. You will not find a movie that presents so inevitably and poignantly the injustices and devastation of US history, even as it perpetrates new forms of them. The movie is loaded with Leftist ideas—they are identifiable thematically, and they stand up thematically—they are thoroughly conceivable; but, we must also understand, TLR’s Leftism is not material. The Lone Ranger acknowledges the problems of history and showcases them tragically and beautifully, but it does not understand its place in and perpetuation of that history.

Under capitalism—and this will hold for most “Conceivably Leftist” movies—when it comes to Leftist cinema, all we will ever have is the conceivable.