It was not a Market Basket bag; of that I am certain. Most every other specific detail has flown out of my memory, but I remember specifically that the bag my big sister handed to me was not one of the ubiquitous ones from Market Basket. It was bigger, deeper, and as such held many more books than a Market Basket bag would have.

“I don’t want any of these,” she said. “Do you want any of them?”

The bag of paperbacks was a gift from the parents of one of my sister’s friends. They’ve long known that both my sister and myself are bookworms with ravenous appetites for all things printed, so this is not the first time such riches have been proffered. But even at a young age, I long since learned that I had no real interest in the kinds of books that this other family offered. Every book they offer up, no matter how exciting the cover, how promising the premise, will eventually be revealed to be about Jesus, about how the Good Book is all you need to get through the day.

I can’t remember if I was eight or nine, but somewhere in that ballpark sounds right. Just old enough to being developing something resembling taste. Or, if not taste — as there is no end to the crap that a voracious reader will imbibe just for the sake of reading, for the sake of having read — at the very least a sense of what I like and dislike.

To be a reader is to be a bit like a magpie. Always something shiny is sparkling to catch your attention, and no matter how densely you pack your nest, always something shiny will still catch your eye. At age 8, there is a stack of books near the head of my bed, the better to grab during the dead of night, when I’ll prop myself as close as I can to the night-light so I can continue reading all through the sleeping hours. At age 28, the stack sits by my side in my apartment as I write this. Twenty years, and it never seems to shrink. I think if it did, I would start to worry.

So it’s an eager boy that begins to pull paperbacks from that bag, a bag that, again, could certainly not have been a Market Basket bag. But the excitement starts to give way as more and more titles come out of the bag. They all share the same writer, Christopher Pike, his name spelled out in garish spray-paint cursive. Each cover shows a young person, mouth agape in horror at some off-illustration terror, with a pithy pull-line intended to entice you to find out just how this tableau of terror came to be.

“They buried Mike. But not deep enough.”

“She saw the future. She saw death.”

“He took a picture of death.”

None grab my interest. I’d already been burned by the Goosebumps books, with their covers promising mayhem and monsters that the final product never seem to live up to, and these seem to be little more than attempts to capture that same aesthetic.

I don’t want that. I want something different.

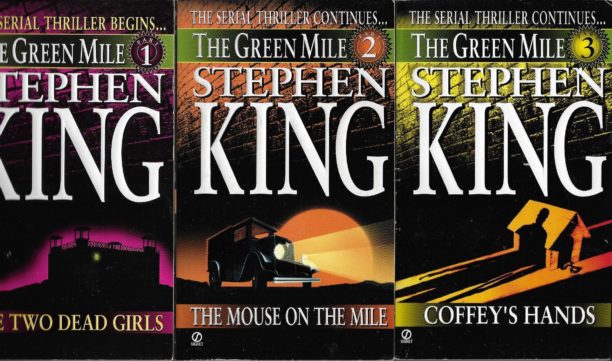

Something different is sitting in the very bottom of the bag, waiting to be found last. These books are different, for they are slim where the Pike texts are hefty. And whereas the Pike books are blasting their macabre natures as broadly as possible, these books possess what can only be described as understated quality.

They don’t need to give you the hard sell. The sell is already there, in the name on top of the books, a name that means nothing to me.

I hold in my hands the six books comprising The Green Mile. Stephen King has found me. And he will never let go.

I feel like everyone has the same Stephen King origin story. We all read our first one way too young, after stumbling over a copy on our parent’s shelf, or in a box in a basement or attic, or stumbled over in a library somewhere. We’re none of us ready. When I read The Green Mile, there was one word that kept recurring over and over again in the descriptions of the various crimes committed by the various criminals awaiting their various deaths on the Death Row cellblock where much of the book’s action takes place. I was so confused as to what this word meant, I did what I always did when faced with such a perplexing puzzle. I asked my Mom what this word meant.

That word was “rape.”

I found myself on the other side of that divide somewhere between then and now. This time it was my younger brother asking if he could read It. He’d seen all the titles on my shelves, he’d heard about what lay between the covers. So while I was away at college, he asked if he could take the plunge.

I told him no. He was still too young. Give it a little more time.

I came home from a long weekend, and was promptly informed that he was about a hundred pages in.

King inadvertently became a barometer for this passage through time. When I was in college, my brother was just a kid, peppering me with questions about the killer clown in the sewers. Now he’s in college, and still our conversations are peppered with talk about that clown, nowadays on account of the movie(s) version. And in the meantime I sit here writing this, wondering how so much time passed in what seems like the blink of an eye.

But however we got here, here we are. Just as everyone who reads King has their first exposure, everyone has their own relationship with the rest of his works. Some people favor the early, lean horror days, while others swear by the sprawling supernatural epics of his 80’s peak. Still others revere his Dark Tower saga above all other works, while others lean more towards his more recent work, stories that are more contemplative and harder to pin down under any genre classification. And still others prefer King when he was liberated from his own name and publishing books under the name of Richard Bachman.

If King has been a constant present in the lives of us, his Constant Readers, then recent times have cranked that presence up to previously unheard-of heights. The past few years have seen not only an explosion of straight adaptations of King’s work, but a new prominence of creatives taking major inspiration from his body of work. Netflix’s delightful Stranger Things, as one super-easy example, has King coded down to its DNA.

It would be easy, then, to take King for granted. To view him less as an artist, a writer, a man, and more as a brand unto himself.

But doing so misses out on the heart of King’s work, the thing that sets him apart from his brethren in shock and horror. King’s works strike a chord because he is uniquely gifted in the ability to capture the humanity of his characters, enabling us to love and care for them on a level we don’t often get in fiction. His heroes and villains feel real pain, share real love, and so when the forces of darkness, supernatural and otherwise, come a-knocking, that feels real as well. King’s books can largely be summed up as being about ordinary people grappling with the extraordinary, sometimes succeeding, sometimes not.

Maybe that’s why King’s work is popping right now. We live in extraordinary times, when horror and panic seem like daily occurrences. King’s fiction does not always portray victory in these struggles, but it always portrays the fight. In King’s world, losers can topple demi-gods, the downtrodden can be proven to be the most powerful, and even the most mediocre of lives can brush against the magical and the divine.

When I took those books from that bag, I had no idea what I was getting into. I had no idea just how much mental real estate would end up being claimed by that writer, or just how much my life would be shaped by his words, both fiction and non (On Writing is basically my Bible).

But looking back at it, I realize now that your first Stephen King book isn’t a book at all. It’s an offer. An invitation. The danse macabre’s been going on for a long time now, and it stands to keep going for longer still. He’s offering you a hand, inviting you into the circle. There’s pain here, but beauty too, and you’ll never be alone.

It’s been twenty years and I’ve never once regretted taking that offer and joining the dance.