Running Press have recently released two very excellent books through their collaboration with Turner Classic Movies. Mark A. Vieira’s Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930-1934) and Donald Bogle’s Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers are both richly illustrated, oversized hardbacks that come in just under coffee table size.

That size thing is kind of important; both books need to be big enough to reproduce the amazing photos included within their pages, especially those in Forbidden Hollywood, which fairly leap off the page with luminescence. However, given that they’re not “coffee table books” in the usual sense (in that they actually have text) and aren’t meant to be looked at, but read, they can’t be massive, weighty tomes.

Sorry. Digression.

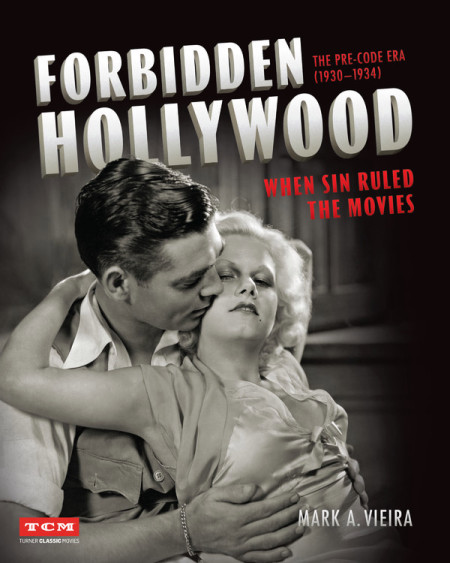

The fact of the matter is that these books are both as lovely to look at as they are to read. Forbidden Hollywood is akin to Kenneth Anger’s infamous book, Hollywood Babylon. The cover to Vieira’s book certainly nods to Anger’s gossip-mongering parcel of lies and half-truths, but Forbidden Hollywood talks more about what happened on-screen as opposed to trafficking in backstage gossip. Honestly, given the plots of some of these movies, one wonders if they could be greenlit today by a major studio, dealing as they did so frankly with topics like prostitution, poverty and the like.

The fact of the matter is that these books are both as lovely to look at as they are to read. Forbidden Hollywood is akin to Kenneth Anger’s infamous book, Hollywood Babylon. The cover to Vieira’s book certainly nods to Anger’s gossip-mongering parcel of lies and half-truths, but Forbidden Hollywood talks more about what happened on-screen as opposed to trafficking in backstage gossip. Honestly, given the plots of some of these movies, one wonders if they could be greenlit today by a major studio, dealing as they did so frankly with topics like prostitution, poverty and the like.

The book essentially traces the moral authorities’ attempts to reign in movies, and how it went from a self-imposed code created to avoid government intrusion into a full-blown, Catholic-sponsored takeover from the outside. The most fascinating aspect of Forbidden Hollywood is that Vieira not only looks at the back and forth between the studios and the moral crusaders, but also at legal proceedings, newspaper editorials, and even the feedback the studios received from the theater owners across the country.

Honestly, nothing grabbed me quite so much as the fact that almost every single one of the 20+ films tackled by Vieira in Forbidden Hollywood feature commentary from theater owners across the country, wherein they describe on a week-by-week basis how their audiences received the films being screened, and what that did to their bottom line. These are unbiased, unfiltered letters from the trenches, and it’s an insight into the era which I’ve never before seen in a book of film history.

Forbidden Hollywood, as it covers a fairly short period of time, is allowed to spend a little more time on each of its films and their part of the story of the Pre-Code era; thus, its 272 pages unfold at a fairly leisurely pace. In comparison, Hollywood Black seems a little rushed at times, but the various sections highlighting actors and directors, particularly those on early notables, make for an engaging read.

As things move past the ’40s and ’50s, Bogle’s book hits more high points rather than delving into possible side avenues, which really does a solid job of reinforcing the point of the book, which is that African-Americans and people of color were ignored for the better part of Hollywood’s history, and it’s only within very recent memory that they’ve been represented on-screen and represented in a way which reflects their real-life experiences.

It’s almost a positive that, once the books hits the ’70s, the pace kicks up a notch, running through list after list of actors, directors, and producers. It’s impressive that Bogle finds time here and there to nod to under-appreciated aspects of film production in order to nod to the likes of costume designer Ruth Carter, whose work has been integral to the visual style of so many films over the last couple of decades.

While the earlier chapters, wherein Bogle has profiles on the likes of Ralph Cooper, director Oscar Micheaux and actress Hattie McDaniels, are arguably the more illuminating and interesting, the latter chapters touch on enough topics with plenty of information to make the reader want to seek out more on each subject. While a deeper analysis of the Blaxploitation phenomenon beyond the surface treatment would be nice, as well as maybe looking at other subgenres, that’s why we have books like Robin R. Means Coleman’s Horror Noire to explore all the possibilities.

Both Mark A. Vieira’s Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930-1934) and Donald Bogle’s Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers are great reads. Forbidden Hollywood offers an in-depth glimpse of a last shining moment, while Hollywood Black provides an essential primer for anyone wanting to get beyond the whitewashed surface of Tinseltown. They’re both out now from Running Press and Turner Classic Movies.