Welcome to THIS JUSTIN, a column dedicated to my love of all things weird and spooky. Each week I’ll be taking you on a deep dive into something creepy and/or crawly and talking your ear off about why I love it so much.

One of the shortcomings of the horror genre is the stock character of the Google Expert (or what the gentlemen over at the Horror Show podcast have deemed “The Mangler Expert” after Ted Levine’s character in The Mangler). This is a character who finds the answer in some ancient tome, or nowadays simply by Googling, often in the nick of time to stop whatever monstrosity the protagonist is facing off against. It’s the embodiment of a deeper problem: how scary can something be if it’s playing by a set of rules? Where’s the terror if the adversary is known to be threatened by holy water or a verse from the Necronomicon? Lovecraft is often cited as the writer who steered horror away from the rational and rule-based, but even he suffered from it: Cthulhu could only rise when the stars were right, the Haunter In The Dark couldn’t stand light, the Hounds Of Tindalos couldn’t move through curved space (okay, that last one was cheating, but Frank Belknap Long was a Lovecraft fanboy so it still counts). Stephen King’s greatest villain It was defeated by the Ritual Of Chud. F. Paul Wilson’s Adversary Cycle centered around a villain who was defeated with an ancient relic. Even vampires can’t come into your house unless you invite them and werewolves are terrified of silver bullets.

Don’t get me wrong, I love those stories to death, but there’s something quaint about monsters and specters and ghouls who play by the rules. Real fear and real terror, the stuff of nightmares, lacks any sort of logic or order. Surreal horror throws every rule out the window. Nothing makes any sense. You are forced to watch (or read) as the bizarre visual cacophony of dread that exists behind your eyes when you sleep is forced back to you. Two creators encapsulate this brand of horror better than anyone else: Bentley Little and Junji Ito. They work in different mediums but both arrive at the same ghastly end. Theirs is a form of chaotic horror, of borderline ridiculousness that dances a fine line between silly and scary; ultimately landing in the realm of absolutely unsettling. It’s a horror of the nonsensical, of the absurd in the truest sense of the word. Theirs is a realm in which horror doesn’t need to be summoned or unleashed. In the worlds of Ito and Little, shit just happens.

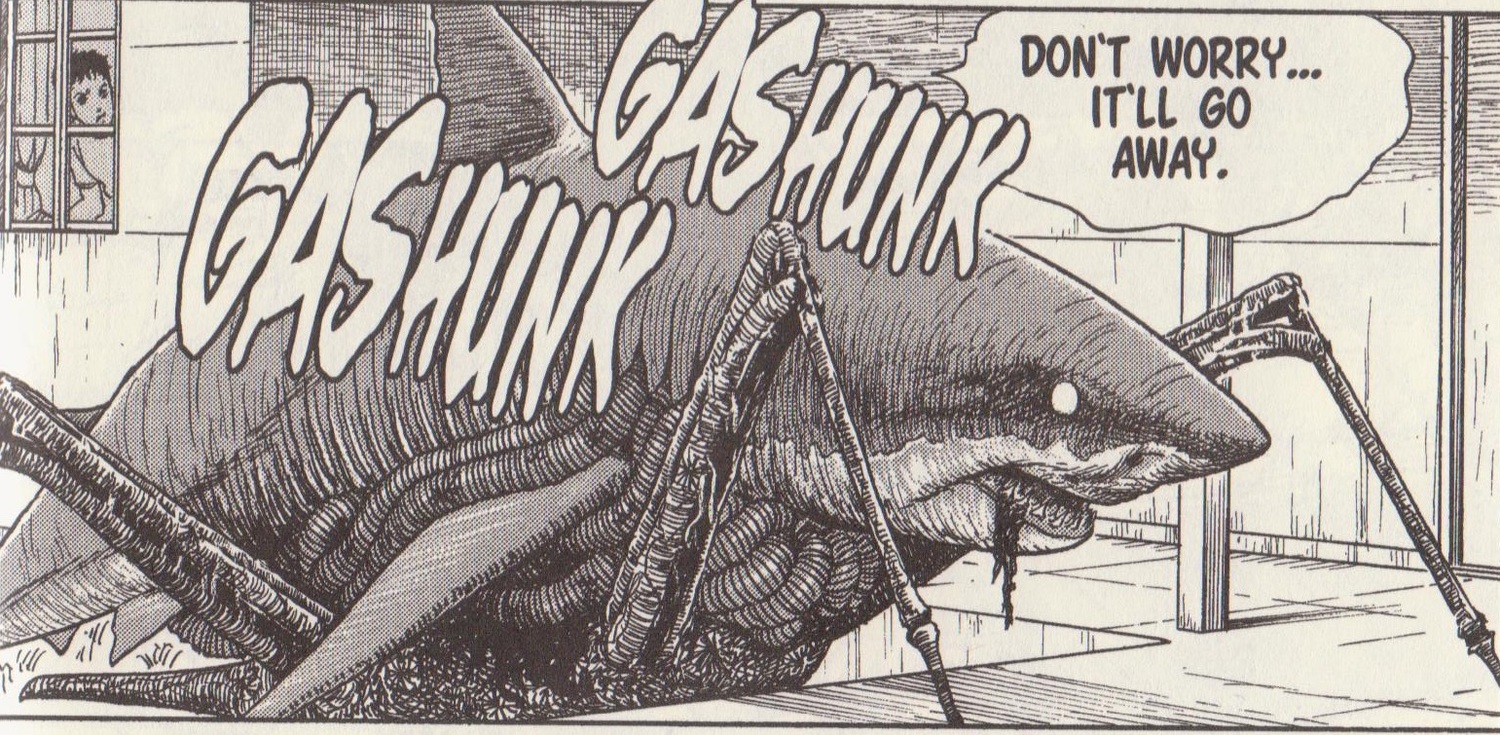

Japan has a rich history of horror in its folklore, literature, and cinema. Thanks to the American versions of films like The Ring and The Grudge, Western audiences have become familiar with the cinema sub-genre of “J-horror.” However, when it comes to a Japanese interpretation of “horror”, it’s in the manga realm, rather than cinema, through the work of artist/writer Junji Ito. Ito’s work is an exercise in visual hellscapes; a combination of Cronenbergian malformities, Lovecraftian creatures, insectile creepiness, and just generally unsettling imagery.

The imagery, as terrifying as it is, is not what sets Ito apart in the horror world. Rather, his almost complete lack of rules or explanations for his bizarre expositions make our skin crawl. Ito’s stories revolve not around traditional monsters per se but more on the concept of hostile forces inflicting their will upon hapless everyday people. His is a universe of malicious chaos, the kind of universe that would exist if an ultimate creator was absolutely sadistic. Things are rarely explained and often the reader is just as in the dark as the characters. Instead of any sort of resolution there is just a cessation of action, often before the protagonist is done away with in some unspeakable way.

Entities without sanity and events without explanation barge into the lives of Ito’s characters. His imagery is ghastly and deeply unsettling to be sure, but the absolute lack of rationality is far more terrifying. In his story “Hanging Blimp,” for example, balloons shaped like heads with nooses dangling beneath swarm cities all across Japan and murder the people they resemble. Think about that.

Yes, the imagery of this story is… almost unbearable to look at in how creepy it is. But the deeper sense of dread comes from the fact that it’s happening in the first place. Almost all of his stories are like that: one day, shit just goes wrong in a monstrous way and his characters just have to roll with it. His characters face horror so surreal and inexplicable that we are left wondering “what the fuck is even happening?” when seeing it for ourselves.

It’s not vampires, or a haunted house, or zombies, or aliens, or anything even remotely close to such classic spookies. There’s a vague hint of Lovecraft to some of his illustrations and non-logic; sometimes a hint another reality lurks just beyond the line of sight for our characters. Most of the time it’s just one day things are normal and then life is hell and chaos in a completely indescribable way.

The fiction of Bentley Little works in a similar fashion, albeit through the written word than through any sort of visual medium. Nonetheless, the images Little conjures up are equally nightmarish. His books often have somewhat derisive and simple titles – The House, The Policy, The Association, The Return – and their plots often follow suit. In The Policy, for example, a couple finds themselves the victims of a sinister insurance salesman who sells them expensive insurance policies for absurd events; if they don’t buy the policies, the event they would have been protected against happens to them in increasingly horrifying and surreal ways. In The Association, the characters find themselves at the mercy of a sinister homeowner’s association.

All of this sounds kind of dumb on paper, but Little uses these somewhat simple plots as springboards for exercises into the absolutely terrifying. Little summons images that are literally the stuff of nightmares. And I mean that in the absolute strictest sense of the phrase. Often, nightmares in books and film are nothing like nightmares in reality. They’re too linear and logical. Little, however, perfectly distills the surreal terror of a nightmare. In The House, a man and his wife are clubbed to death by little people with clown faces accompanied by a swarm of insects with the heads of screaming infants. And in The Policy, when a couple refuses an upgrade to their maternity policy, they are forced to give birth in a hospital decorated with paintings of grotesque clowns and a tall, thin doctor dressed all in black wearing a cherub mask who castrates their son, exclaiming in a high-pitched voice, “it’s a girl!” Even his stories that are variations on a classic horror theme carry a unique flavor. The Summoning, a vampire story, isn’t just about an undead ghoul that drinks the blood of the living. The creature also takes the shape of what its followers believe is a character that can never die – for many people in the story, Jesus Christ. So, for much of that novel we have a vampire, masquerading as Christ, spouting obscenities for its followers to carry out: bring me a child to devour; tie your kids to a cross in your backyard at night so I can eat them; murder the Chinese-American population of the town; force your employees at the bank to wear uniforms made from underwear you found in a thrift store because I think it’s funny. This never happens in more “traditional” vampire stories.

His stories often start to slide into the realm of the surreal with something slightly off; odd enough to make the characters themselves question whether or not they’d actually witnessed it. The weirdness grows exponentially and soon everyday life is violently ripped open, injected with surreal and absurd terrors that are given little explanation. Mundane objects take on ominous qualities: a character is unnerved by a poster on his wall; another is unsettled by the texture and color of a businessman’s suit; and a third finds a single strand of hair sticking up on the back of their dentist’s head disquieting. Little weaves masterpieces out of these seemingly nonsensical plot points, like a series of vignettes barely held together, and similarly to Ito’s work they oftentimes just happen. There is no rationale behind the events, no logic: just a horrifying and eerie chaotic force that shows up and starts smashing to bits any sense of normalcy and reasoning. Little’s characters are unable to comprehend what they are facing and the hopelessness they feel is just as unsettling as the horror they are dealing with.

Ultimately, the end point of the work of these two writers is absurdity. Both Ito and Little excel at creating works of art that make little to no sense and often times have only a bare minimum of narrative causality. The key difference is that Ito is concerned more with creating something absurdly monstrous, whereas Little’s goal is to achieve the creation of the monstrously absurd. Both offer stories set in a universe that is inherently hostile to humanity, but the way that hostility manifests itself is different. Ito leans more towards the horror manifesting itself through the human body, a Cronenbergian concept wherein the body rebels against the owner and becomes something else entirely. An external will is oftentimes exercised upon Ito’s characters, compelling them to change themselves either voluntarily or involuntarily, ultimately into something that defies explanation and rationality.

Little, on the other hand, steers away from the Lovecraft/Cronenberg flavors and chooses to turn American suburban life into his playground. He often employs taboo-shattering scenarios that make the reader squirm as much as the more horror-centric aspects of his work. Characters are driven to acts of incest and cannibalism. Spouses find their partners engaging in acts of coprophagia and urolagnia. Children are frequently the target of acts of murder and torture. Deviant sexual practices are often used as a way of showing just how off the rails the reality of the characters has become. Think of the work of David Lynch turned up to eleven and laden with actual overt supernatural elements: like Blue Velvet with the eroticism pushed into the realm of the obscene and grotesque, or if Mulholland Drive was just the Dumpster Monster and the Cowboy threatening Naomi Watts throughout the whole film. Both creators excel at a sort of freeform method of storytelling that is barely controlled chaos, a madness that is loosely reigned in just enough to tell a coherent story. Their characters are at the mercy of not only something they don’t understand but something that quite possibly they cannot understand; powers that reject any attempt to frame them in any reasonable and comprehensible way.

People find comfort in cause and effect; A follows B which is followed by C. Routine and order dictate our lives and keep us running smoothly. Junji Ito and Bentley Little are more than happy to show that the greatest horror of all is the diversion of that. For them, the smashing of normalcy, the utter obliteration of routines, that is what is truly scary. In the absurd, they find the terrifying. In the ridiculous, they find a truly frightening vision that few other creators come close to.