Originally, I was going to title this article “The Howling is the Best Werewolf Movie of 1981, Fight Me,” but a friend suggested that might be unnecessarily aggressive. First, let it be known that I like the other major 1981 werewolf movie, An American Werewolf in London, just fine. It is an entertaining, well-made film. But The Howling is better. Let me also preface this by saying that I love werewolf movies, but that I also have very specific preferences when it comes to the genre. Broadly speaking, here are Trey’s Rules for Effective Werewolf Movies:

- Bipedal werewolves – this really is a must. If the creature on screen isn’t a wolf-man(or woman) then it’s just a big dog and that’s way less interesting.

- Practical effects – This criterion is getting harder to enforce, and to be honest I’ve seen some combinations of practical and digital that look pretty good. However, my heart will always belong to the old ways of yak hair, rubber/latex, and spirit gum.

- The werewolf must transform on screen at least once. That’s kind of what everyone is buying their ticket to see, anyway.

- There should be knowable rules to how lycanthropy works: its causes, and how to kill the werewolf. They don’t all have to follow the same rules necessarily (although I do prefer the weakness to silver), but there should at least be consistency within the diegesis.

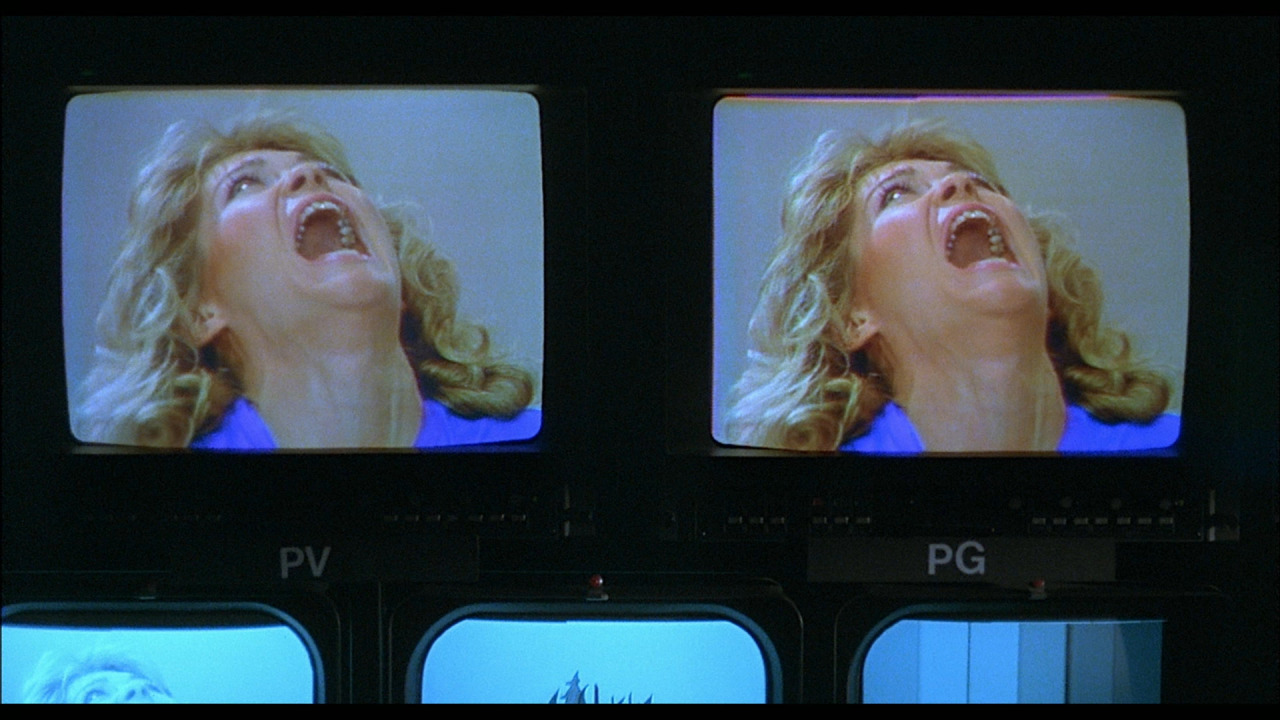

Joe Dante’s film (with a script by John Sayles and Terrence H. Winkless) follows all of these rules, but it is distinct among other famous/well-regarded werewolf movies in that the protagonist is not the killer lycanthrope who drives the plot. Instead, the initial setup owes a lot to the horror-mystery/early slasher phase of the late ’70s/early ’80s, with TV journalist Karen White (Dee Wallace) helping the police track down a murderer who has become obsessed with her. After that inciting incident, we have two parallel threads, with White and her husband Bill (Christopher Stone) trying to confront the trauma of the experience at her therapist’s experimental resort facility called “the Colony,” while her coworkers Terri (Belinda Balaski) and Chris (Dennis Dugan) investigate the mystery of her attacker, Eddie Quist (Robert Picardo at his absolute creepiest). Thus, instead of beginning the film with the transmission of lycanthropy and focusing the film around the horror and tragedy of that curse, The Howling engages with the protagonist’s very human response to physical and emotional trauma separate and distinct from the very gradual unveiling of the werewolf threat.

***Spoilers will follow***

(The Howling is a 37-year-old movie, so I feel a little silly posting this warning, but it’s also not as well-known as movies like American Werewolf and I don’t want to rob anyone of the fun of experiencing it for the first time)

The twist of the film, which seems fairly unique for the time, is that the threat is not a single werewolf. Rather, the Colony is a collective of New Age werewolves, organized by Dr. Waggner (Patrick Macnee) in an attempt to keep up with the times. In a sense, the werewolves’ objective is also that of the film itself. Werewolves, as with other classic movie monsters like vampires, are creatures of the Old World and were the stuff of Universal and Hammer period horror (actually The Wolf Man has a more or less contemporary setting relative to its 1941 production, but its Welsh setting and black & white photography lend it a sense of “past-ness). The Howling drags its monsters into the neon and pop psychology of early ’80s Los Angeles. In doing so, it would be tempting to devolve into horror-comedy, if not outright parody. But The Howling mostly plays its monsters straight. It’s a very funny film at times, but the humor is usually derived from its playing with audience expectations based on decades of prior films in the genre, as well as meta-references to those past werewolf movies. The humor never undermines or dilutes the horror elements, but merely provides an extra bit of fun for viewers “in the know.”

One of the things I love most is how the various werewolf characters respond to Waggner’s efforts. Horror legend John Carradine is the elder of the pack, and while constrained by the rules of the Colony, is alternately hilarious and pathetic as he laments his physical condition. Marsha (Elisabeth Brooks), even within the confines of the Colony, is unable to hold back what Waggner calls her “natural energy,” and she ultimately seduces and turns Karen’s husband in the film’s infamous werewolf sex scene. Say what you will, but I find the one shot of animated werewolves charming. Slim Pickens is the charmingly goofy old sheriff (who also happens to be a werewolf). And Eddie of course has left the Colony and killed numerous people in LA, and the combination of his violent tendencies, lycanthropic abilities, and the teachings of Dr. Waggner have given him a kind of megalomania that fuels his stalking of Karen. With so many werewolves, it is impressive that The Howling manages to give them distinct characterizations and personalities. They are types, to be sure, but clearly defined types with their own motivations and desires. And I enjoy the film’s seeming rejection of Waggner’s junk psychology; once Karen is bitten, she is not immediately overwhelmed by the impulses and “natural energy” exhibited by the Colony, but instead exhibits enough self-control to both reveal the werewolves’ secret to the world and put an end to her curse.

In addition to the way The Howling updates and revises the conventions of the subgenre, it also has really effective werewolf effects. Dante draws out the full reveal of the monsters for as long as possible, keeping Eddie and his kin in the shadows and only giving us partial glimpses of legs, claws, etc. It’s fairly late in the movie when Eddie fully reveals himself and transforms on camera. These effects, created by Rick Baker protégé Rob Bottin in his first major solo effort, are really impressive and hold up to contemporary viewings. Comparisons to Baker’s own designs from An American Werewolf in London are perhaps unavoidable, but I think the two scenes work very differently. Baker’s transformation sequence captures the surprise and pain of a person transforming for the first time, and unwillingly at that. By contrast, Eddie Quist is showing off. His shift, while laborious, is not painful but rather a kind of power play meant to intimidate. American Werewolf is frightening because we sympathize with the man who is transforming; The Howling works because we sympathize with the woman trapped in the room with the monster. Both are incredibly effective in their own ways, but the combination of Bottin’s makeup/prosthetic effects and Robert Picardo’s fantastically unsettling performance makes for one of the best cinematic werewolves of all time.

The Howling is one of the best modern werewolf films, full stop. And yet I can’t help but think that it deserves far more attention and respect than it has gotten. I’m thankful that Scream Factory has released a gorgeous collector’s edition Blu-ray with plenty of special features, and this Halloween season it’s also streaming on Shudder. Thanks to the cleverness of Joe Dante’s direction and John Sayles’ screenplay, The Howling is a film that knows where it came from, but resists simply repeating beat-by-beat the tropes of the past. Besides that, it’s better than An American Werewolf in London.