Obsession has long been a source of horror in the genre; the “obsessed partner/fan/neighbor” is a stock character up there with “weird guy at the gas station” and “evil stepfather”. And sometimes, this trope can bear the sweetest of fruit: Fatal Attraction and Vertigo stand out as two examples of films that deal with such a concept. Joe DeBoer and Kyle McConaghy’s Dead Mail takes the idea of being obsessed with someone and uses it as a springboard into a truly fascinating film, a weird sort of neo-noir mystery where actually is no mystery, only a steadily ticking countdown to more mayhem.

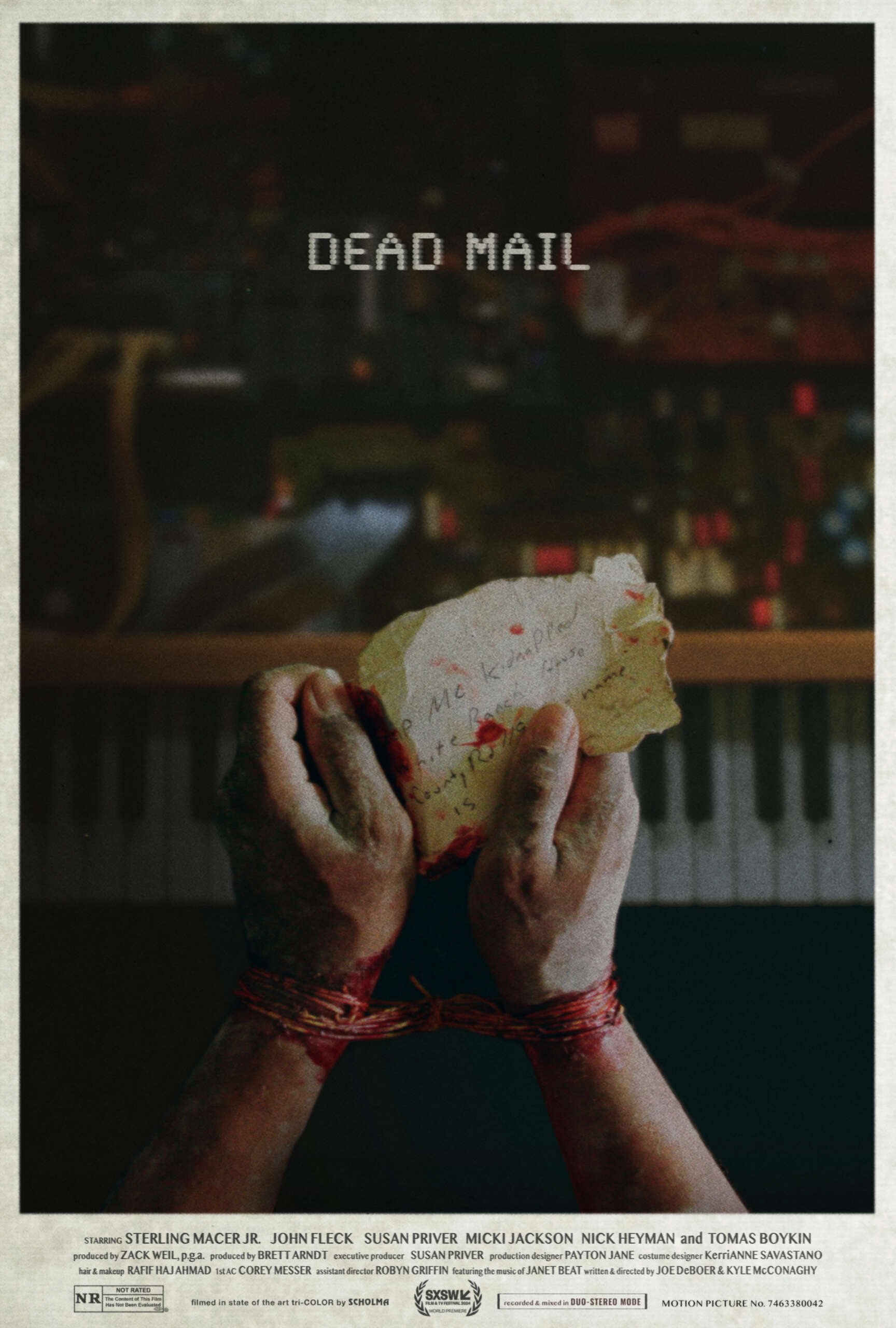

Jasper is a simple man. He enjoys assembling models in his free time, he lives at a local men’s hostel, and he’s well-liked by his coworkers at the post office. He also has an almost uncanny ability to track down would be recipients of “dead mail” letters; that is, mail that is deemed undeliverable and is returned to the post office. One day, Jasper receives an ominous item at his desk: a scrap of paper, stained with blood, with a message hastily scribbled on it from someone claiming to have been kidnapped and held at a white studio house on a county road. Jasper gets down to brass tacks to track down the source of this letter, and the film spirals into a strange hybrid of murder mystery, spy films, detective fiction, and even a touch of giallo.

The look of this film fully sells the idea of it taking place in the late ‘70s. Everything about it from the grain of the footage, to the costume and hairstyle choices, and the bland beige office settings puts the audience in that almost nostalgic feeling for the utterly boring era of bureaucratic monotony that was the late ‘70s/early ‘80s. This makes the film seem even more hellish and unsettling, as it immerses us into a bygone era that serves as the uninterested backdrop for a horrific crime. The plots involvement of now vintage stereo equipment and electronic instrumentation draws us in even further, never laying on the nostalgia too thick but doing so just enough to highlight the contrast between the ghastliness of the plot and the dull “thereness” of the setting and aesthetic.

The performances in this film are stellar. John Fleck and Sterling Macer Jr. as the slimy obsessed businessman Trent and unfortunate electronics genius Josh respectively are the core of this movie. Macer’s quiet and mild-mannered Josh has almost an evil twin in Fleck’s Trent, in that Fleck depicts someone who is equally meek but more so because anything other than meekness would probably be absolute violence. The two are in constant struggle with one another, either over business ventures early on or over actual life and death as the film progresses. Trent is a terrifying blank slate of a human being, a slimy nothingperson that has nothing going on under the surface aside from whatever obsession they have going on at the moment, and Fleck goes even further by infusing the character with an infuriating and pathetic mewling quality, almost like the archetypical incel that bemoans their lack of intimacy with women by projecting a vile misogyny out into the world. Macer’s Josh, on the other hand, is the exact opposite of that. He is quiet, clearly intelligent, and passionate about electronic music, and seems to be an extremely likeable guy. His suffering at the hands of Trent speaks to the audience, and it is this push/pull that forms much of the drama of the film. Tomas Boykin as Jasper is amazing, a super competent and highly intelligent man content with his job of tracking down dead letters and delivering them to their intended recipients. Boykin gives his character a tragic sort of “underachiever” vibe; he is clearly extremely intelligent and has connections to some odd places in society, and yet he is just happy working in his basement office and building his models in his free time. Like, Macer’s Josh, Boykin’s Jasper is just a good guy, the kind of coworker you wouldn’t mind running into outside of work.

Dead Mail is a quirky little movie that you think you have a grasp on, but it keeps slipping and sliding all over the place anyway, an off-kilter labyrinth that twists and turns through the seemingly familiar into the subtly unsettling territory of the classic noir and giallo films. It feels authentic, having none of the false notes that so many “throwback” films often suffer from. Ripe with tension, its slow burn approach to the story it’s telling is genuinely satisfying, and it never feels stale or meandering.