I’ve often spoken of how nostalgia is a very powerful factor in how we view art. It is a lens that is both effective and unreliable when consuming art; if we develop an attachment to something at an age that we might not be too discerning between good art and bad art, that attachment lingers. I mean, just look at me: I’m 34 years old and I’m still terrified of a book I read when I was a kid. I’ve grown older, and I’m no longer afraid (that much) of aliens and the ’88 version of The Blob. The goopy zombies from Return Of The Living Dead III are laughably bad now and the end of The Fly II is just sad. But…certain things from my childhood are still effective because they got to me at a young age, and they made an impression. They got under my skin and into my brain and my heart and they stayed there. My fears have become more complex and harder to dismiss: loved ones and pets dying. Job loss. A bad economy. A racist, xenophobic, misogynist lunatic in the White House. Cancer. But at the end of the day, that book I read when I was a kid is still at the heart of me as a person. It’s still there as the measuring stick when it comes to horror, the gold standard by which all other art I consume is held up to.

That book was Stephen King’s It. My feelings on it are well documented so I’ll spare you my personal history on the book but if you want you can go HERE to read a piece I wrote or go and listen to a little contribution I did for a friend’s podcast HERE. If you know me you know how much this book means to me. You also probably know I’m not a fan at all of the 1990 miniseries. I think it’s way too clunky, way too cheesy, way too ‘90s. The actors in it are all competent; the late Jonathan Brandis plays Bill Denbrough earnestly and it’s fine but it’s not It. I felt that the feeling of dread, and anxiety, and absolutely nerve-jangling fear that the novel drips with is difficult to replicate on screen, and the ‘90s miniseries was a half-hearted attempt at best to translate something that needed more than was possible at the time for a network TV adaptation. And for better or worse, it shows. But for years it was all I had, so I dealt with it.

I remember a few years back after the first season of True Detective blew up and Cary Fukunaga was the hot to trot new kid on the block getting really excited upon hearing he was writing and slated to direct a new cinematic adaption of my beloved book. News came here and there; New Line was making two films instead of one, the kid from We’re The Millers was playing Pennywise, then Tilda Swinton was in talks to play Pennywise, then Fukunaga left, taking the We’re The Millers guy with him, and even for one hellish moment it seemed like the film was going to be stuck in pre-production limbo forever. Eventually, Andy Muschietti, director of one of my favorite movies of the past few years (Mama), entered the picture and things started picking up; the first image of Bill Skarsgard as Pennywise dropped and the world held its breath and then the trailer dropped and the whirlwind continued and now…here I am, brain still dissecting what I saw tonight, heart still racing from the eldritch assembly of images I watched play out across the silver screen.

It was…everything I hoped for and then some. I don’t know what kind of expectations I had going in, honestly. I wanted it to be good and I hoped it would be good but I’d been wronged before so I was nervous. I was prepared for this film to suck. I was prepared to continue existing in a world where the terrible essence of King’s work had yet again failed to be captured onto film. But I was not disappointed in the least by this movie. Not even close. From the moment George meets the titular creature in the form of the iconic Pennywise The Dancing Clown to the last scene of the Losers Club saying goodbye after defeating It (hopefully), this film is a near nonstop sequence of anxiety and full-blown fear. Muschietti builds a true atmosphere of dread, creating both terror and horror in copious amounts in the viewer. He conjures up images of dead children and lepers; malicious paintings come to life (poor Stan Uris is subjected to one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen in a film) and tendrils of hair coiling out of a bathroom sink to ensnare children. The cinematography in this film is chock full of Dutch angles and dolly zooms, as well as some clever perspective tricks that are truly disorientating and unsettling. The film has a very surreal and dreamlike sense to it, especially the scenes where It is present. Imagine the dumpster transient scene in Mulholland Dr. and the lead up to it; that’s most of this movie. It’s that tense. There are certain scenes, particularly Ben researching the Ironworks Explosion at the library, that feel like we’re watching a bad dream unfold and, bound to the frightening logic of such things, are helpless to look away. Muschietti takes what he did with Mama and pushes it into overdrive to guide us into a waking nightmare of a film.

Of course when it comes to It the big question is, ‘How was Pennywise?’ After all, what would an adaption of It be without a Pennywise that scared the pants off us? Rest assured, Bill Skarsgard excels as Robert Gray aka Pennywise The Dancing Clown. This is not the theatrical goofball Tim Curry played. Skarsgard’s Pennywise is less a cackling carnival barker and more a sadistic predator delighting in the suffering he’s causing. At times I was reminded of a demonic Chop Top from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Skarsgard’s delivery comes off as almost sexual at times, particularly during his first appearance when Pennywise meets George. His tone and cadence resemble that of a child molester carefully isolating their victim and luring them way from safety, with perhaps a touch of a junkie desperate for a fix.. He is savage and animalistic, a poor fitting human costume for something wholly and truly inhuman, and I think that is what sets his performance apart from Tim Curry. Tim Curry was portraying an evil clown who killed children and only in one throwaway line reveals he eats them, while Skarsgard plays one facet of some horrendous entity — “with more faces than Lon Chaney” — who reveled in the pain and torment of children before killing and eating them. When the mask of Pennywise the Clown is dropped and we see what It wants Its victims to see, it is literally like something out of a bad dream.

The creature never feels far off in this film, always just around the corner or behind the door or in the refrigerator. And I cannot stress how well Muschietti highlights the amorphous nature of It. His Pennywise is chaos made flesh, a jittering, twitching mess of a monster that seems almost uncomfortable unless moving and shifting, protean and unpredictable, and it uses this nature to generate the fear it so desperately craves. With jaundiced eyes looking off in different directions and a mouth full of needle-like teeth, Skarsgard lays to rest any doubt that he couldn’t fill the shoes of Tim Curry. That being said, Skarsgard isn’t the only actor bringing Its avatars to life; Tatum Lee is nightmarish as a character billed only as “Judith” and Javier Botet, a personal favorite of mine after playing the titular character in Muschietti’s Mama, brings one of King’s greatest horrors to the silver screen: the leper under the house on Neibolt Street, a cackling rotting creature that lurches after a screaming Eddie Kaspbrak.

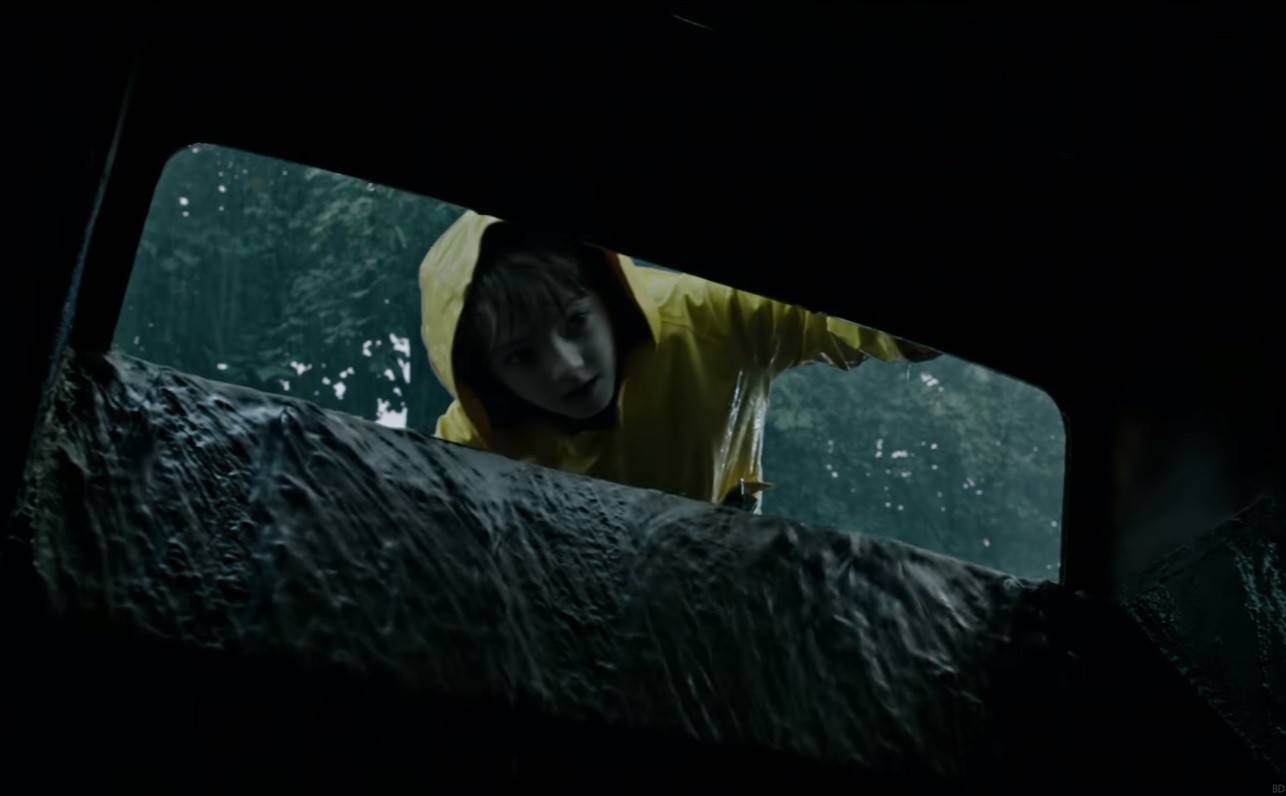

Let’s talk for a second about the recreation of the iconic scene from the ‘90s miniseries. There was buzz earlier in the summer that in this version, Bill does not know his brother is dead, only that he’s missing. I can assure you that George is indeed very dead, and that is not a spoiler in the least because his death is incredibly gruesome and tragic and vivid and nothing I write will do it justice. Even knowing ahead of time that Georgie dies, you will likely be unsettled when it occurs. This is not a slow zoom-in on Tim Curry’s yawning fang-filled mouth, or King’s “what he saw made his worst imaginings of the thing in the cellar look like sweet dreams” and the relatively tame description of having his arm pulled off. No, there is no Lovecraftian cop-out or half-assed vagueness when it comes to George’s death in this version. We know exactly what happens to George, and it is brutal, and we witness every single terrible second of it. I think it was this moment early on that the vision of Muschietti becomes apparent, as well as the advancement in effects and the lack of limitations an R rating allowed. It also added a nice little touch from the novel in the depiction of the color of Pennywise’s eyes: when George first sees them in the sewer, they are “the eyes he always imagined he saw in the basement,” bestial and yellow. A second later, they are a “bright, dancing blue” like his brother Bill’s eyes. It’s a nice little touch that shows Muschietti’s dedication to bringing King’s vision to life. As I mentioned before, Skarsgard in this scene plays up the predatory nature of It and the result is something almost lustful. His unintentional drooling from the fang prosthetics makes him seem even more craven and bestial, and when It finally has George where It wants him and the mask starts to slip, whoo boy. Pure nightmare fuel.

The acting aside from Skarsgard was stellar for the most part. The Losers Club all have a natural chemistry with one another, with Finn Wolfhard’s Richie Tozier and Jeremy Ray Taylor’s Ben Hanscom standing out for me. They’re outcasts, but they’re cool outcasts, the kind of kids we all wished we could be when we were kids ourselves. In a fitting tribute to Stephen King’s ability to paint pictures both horrific and beautiful, Muschietti is equally at home portraying the innocence of childhood and the nightmarishness of the situation the Losers find themselves in. Ben’s crush on Bev, for instance, is brought to life so beautifully without falling into the saccharine nonsense such depictions often fall prey to. Bev’s own crush on Bill is similarly depicted, and the end result is a gorgeous picture of that sloppy sweet puppy love that everyone can relate to. Bill’s heartache over losing his brother is also fleshed out excellently by Jaeden Leiberher. While he spends most of the movie not knowing if Georgie is dead or not might have set off some alarms in diehard fans initially, the payoff for him realizing that Georgie is indeed gone and never coming back is worth it.

Stephen Bougart and Molly Atkinson as Mr. Marsh and Ms. Kasbrak play their characters perfectly. Alvin Marsh in this version is not just merely physically abusive towards his daughter. Muschietti take something that was never explicitly discussed in the book but was only hinted at as a fear of Bev and her mother and made it front and center of Bev’s relationship with her dad; instead of hitting her the abuse is sexual. Bougart excels at creating a character that is loathsome and disgusting, one whose every word is dripping with sick innuendo towards his own daughter. And Atkinson is a fevered and frazzled mess of a mother, a quietly domineering woman dedicated to keeping her only child on a tight leash by convincing him he is asthmatic and under siege by all sorts of ailments. It might be the front and center villain of this story, but Muschietti lets us know that his Derry is full of bad guys of the human variety who are just as lethal and untrustworthy as Pennywise.

So before I finish here, let me pump the brakes and talk about what I didn’t like. While I said the acting was good for the most part, when it’s not good it’s really not good. While the Losers Club by and large are on point, their counterparts in the Bowers gang felt like paper tigers. Their acting and dialogue are wooden and flat, and there isn’t much character development throughout the film. Henry Bowers, instead of being a truly dangerous individual, is depicted as not much more than white trash with an attitude. Actor Nicholas Hamilton’s acting when he’s just being a dickhead are fine, but when he tries to go full blown badass it’s almost silly. It makes the few scenes with him and his gang fall even shorter and seem even less present. Belch Huggins and Victor Criss are stage props to take up space on the screen, and Patrick Hockstetter, whose death in the novel is brilliant and bladder emptying, is reduced to a throwaway character who dies with but a whimper twenty minutes into the film. Even some of the characterization of some of the Losers felt incomplete. Eddie’s hypochondria, front and center of his character in the novel, is almost a footnote in this movie, as is Stan’s germophobia and obsession with neatness and order. And while Stan’s definitely played to be the weak link in the chain in the movie, I don’t know if the film was successful in getting that across or if I was only getting that because I knew it from reading the book. None of those things were deal breakers for me, mind you, but if you’re someone who is obsessed with flawless acting and character development it might stick in your craw. And, finally, while this is more a personal gripe than anything else, I’m sad we didn’t see more of Eddie Corcoran. His death in the book at the hands and fins of the Gill Man is incredible, while in this movie he is merely mentioned as another victim of It.

I really enjoyed this movie. I’m not sure how impartial I can be given both my love for the novel and my contempt for the TV miniseries, but I suspect I would have enjoyed it even if I loved the miniseries and had never read the book. It was worth the wait over the past few years and it’s worthy of the source material. Sure, it deviates from that material at points, but it does so in a way that is interesting and tasteful. It’s a heartfelt tribute to childhood in every way, be it the sweetness of first love, the camaraderie of friendship, or the terrors of contemplating the death of those close to us. The film is a perfect tribute to this generation’s golden age (the 1980s) without being overly “look at this ‘80s reference! Get it? It takes place in the ‘80s’.” And, most importantly, it captures the nature of the book, the truly deep fear that King committed to paper 30 years ago, the uncertainty of adolescence and all the dangers we see in the world at that time. I read one review that called this movie “Stand By Me but with an evil clown,” and I was kind of aghast that someone would say that as a bad thing because that’s not really far from King’s intent in the novel. I’m excited for the second chapter in a few years, in which we see the Losers as adults, and for more of Its backstory to be interpreted by Muschietti, as well as certain scenes from the adult part of the book (the death of Adrian Mellon at the hands of Skarsgard’s Pennywise has potential to be insane). So if you want to see a good, scary movie with a ton of heart, go see this. You won’t be disappointed.