FILMS FROM THE VOID is a journey through junk bins, late night revivals, under seen recesses and reject piles as we try to find forgotten gems and lesser known classics. Join us as we lose our minds sorting through the strange, the sleazy, the sincere and the slop from the past and try to make sense of it all.

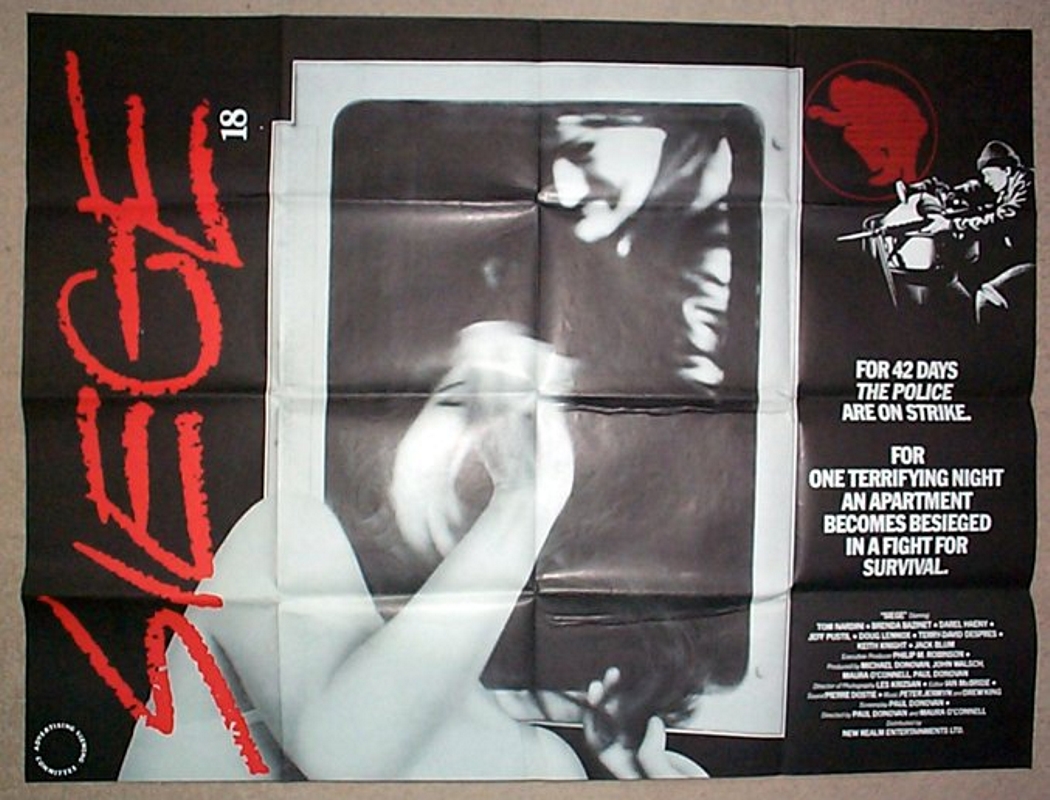

Siege

I know you’re all hyped to see Jeremy Saulnier’s follow up to Blue Ruin, Green Room. It’s a siege movie! It’s about punks fighting skins! It’s a siege movie about punks fighting skins! That’s pretty exciting, right? A genre film with a tense political undercurrent that plays off modern fears, is something that, while starting to occur more frequently, we don’t get often enough. But before you rush over to your locally-sourced, organically-grown independent movie theater and pay to see Green Room, let me suggest a warm-up film: 1983’s Siege (aka Self Defense).

Green Room and Siege have a lot in common. They’re both tight, small productions that focus on one location, and that’s because they’re both siege films! What does that mean? Well, they’re about characters boxed into one location who have to defend themselves from an oncoming horde. That sounds a lot like a zombie film, sure, but at their core all good siege films are about people fighting for a better future rather than focusing narrowly on surviving in the present. The zombies in a siege film, whether it’s a western like Rio Bravo, an urban thriller like Assault on Precinct 13, or a modern punksploitation film like Green Room, are the specters of the past, not literally physical monsters emerging from the grave to lumber toward the screen but monstrous ideas not yet dead and shambling through our daily lives. In Rio Bravo, it’s a societal moral decline and lowered expectations; in Assault on Precinct 13, it’s race relations; and in Green Room, it’s white supremacy. Siege’s zombies aren’t that different. They’re also beliefs that threaten to destroy the foundation of a pluralistic society: intolerance and bigotry.

Siege is set during a police strike in Halifax, Canada. This is important because it establishes the climate under which the “siege” referred to in the movie’s title could believably take place, but also because it immediately establishes the film’s villains: the police. A group of fed-up officers decide to abandon the picket line to exact justice on the segments of city they believe are responsible for society’s moral decay. Their first target is an underground members-only gay nightclub. Clad in armbands not-so-subtly invoking the Waffen-SS, they storm the club and set the film into motion by unintentionally murdering the bartender. Thankfully, a patron is able to escape; unfortunately, his only shelter is a run-down apartment in a deserted part of the city, filled with college students.

Almost immediately it’s easy to see that Siege wasn’t a film that was going to endear itself to everybody. It has a very specific goal and a very antagonistic way of getting there. So much so that it’s hard to discern who the audience for this was supposed to be. Siege is a low-budget exploitation thriller that asked early ‘80s video store customers, people more likely to be looking for schlock like Sledgehammer, to root against a group of violent homophobes. It doesn’t Other its survivor, Daniel, in the way other films dealing in similar subject matter like Cruising or City in Panic do, but it does allows its bigots ample room to speak their distorted worldview and eventually allows Daniel to temporarily fall into a victim-needing-to-be-rescued role. So, it’s a film with a noble cause, but it’s also a film that actively antagonizes every possible group that might find it appealing.

This isn’t me arguing you should skip Siege, however. I started this piece saying the exact opposite, right? Siege is a gripping, white-knuckle thriller. While it may have had issues finding an audience, it absolutely hits the mark on wringing suspense from the those that do stumble upon it. It takes a simple premise, a group of people trapped in a small space, and finds creative ways to make the film seem like much more. It uses everyday objects to create low-budget action set-pieces that are equally absurd and satisfying: a bow-and-arrow, a makeshift electrocution, and a MacGyvered rocket launcher with added shrapnel! It also includes a late plot twist that subverts the traditional happy ending, adding to the film’s grim tone. It understands the mechanics of a siege film and toys with the sub-genre’s conventions enough to continually tighten the screws on the viewer.

Time should have been kinder to Siege. A film like this could get made in 1983 but wouldn’t find its audience. Today, we have Green Room seeing a wide release internationally. That Siege is still an obscure Canadian curiosity hidden from the world on probably a few dozen VHS tapes is unfortunate. It’s not just competent, it’s a legitimately well-made film that plays with audience expectations and stands alongside the best its tiny sub-genre has to offer.