Most coming-of-age films, when it comes to dealing with the uncertainty of where one stands in the twilight of childhood facing the dawn of adulthood, tend to either gloss over that horrid feeling of not knowing or romanticize it. David Depesseville’s Astrakan is not such a film. Instead of presenting this time with a palatable coating of saccharine sweetness to move the narrative along, Depesseville tells a story that is incredibly melancholy, almost nihilistic at times, is often borderline gross, but in the end turns out to be strangely hopeful and liberating.

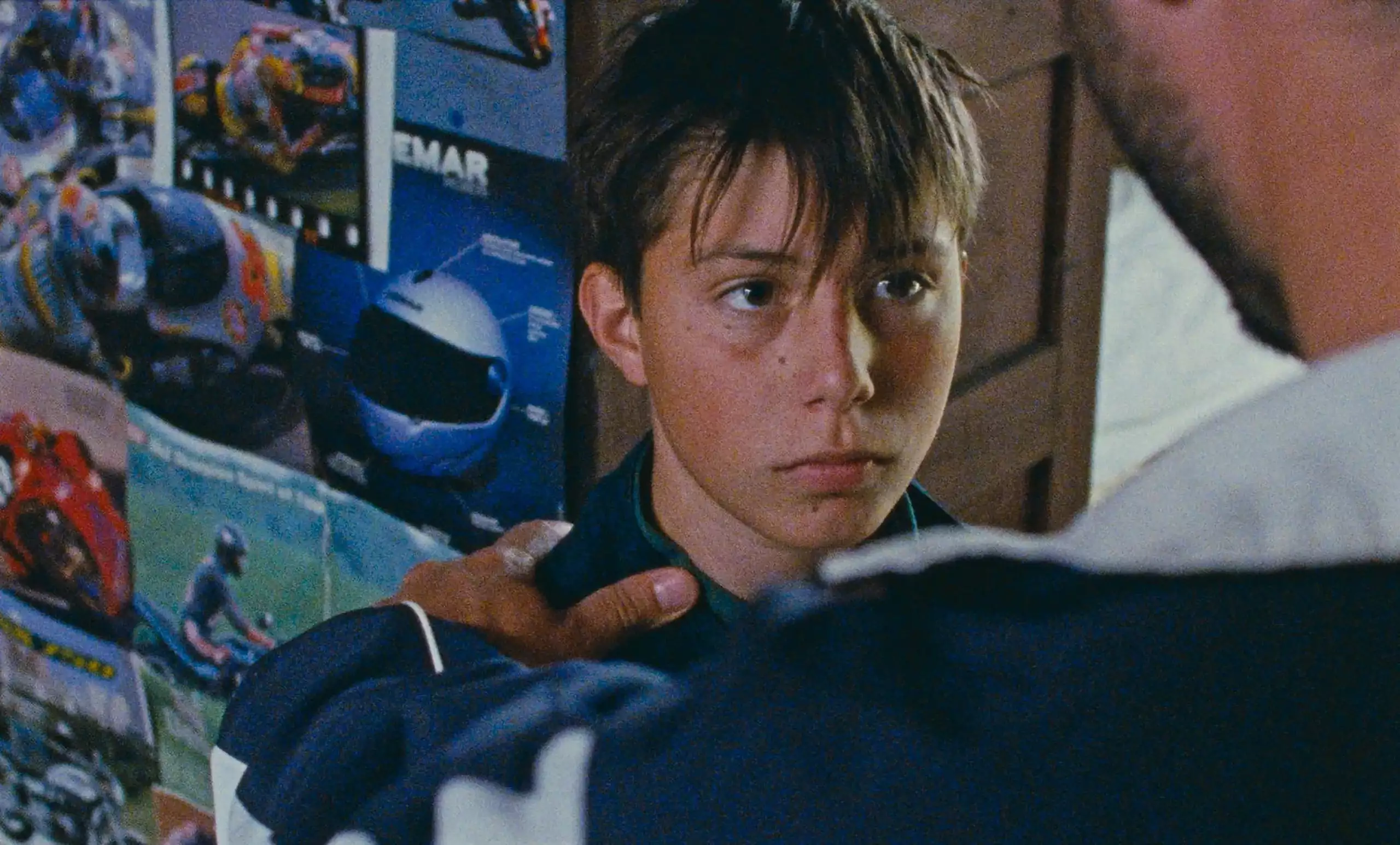

Astrakan is the story of Samuel, a young teenaged orphan living with a foster family in northern France. Samuel isn’t having the easiest time. His relationship with his foster family is at best cordial with occasional bits of genuine affection from his foster mother, and at worst violently abusive at the hands of his otherwise meek foster father. He remains detached from the other kids living there, has caught the romantic attention of his neighbor and schoolmate Helene, excels at gymnastics, and may or may not be the subject of his foster mothers’ brother’s pedophilic desire. It is in this maelstrom that the audience is plunged into as we watch Samuel’s budding pubescent self emerge and struggle to figure out his place in the world.

A central theme of the film is the concept of a pubescent child being unknowable to their parents. As a foster child, there is already a sense of detachment between Sam and his foster family, and that sense of detachment is only increased by how strange Sam is. He is a true outsider: abrasive, aloof, cursed with halitosis, prone to violent outbursts, possibly shitting his pants to spite his foster parents (seriously). Depesseville may take Sam’s personality to the extreme but in doing so he calls to mind the alienation and the isolation and the sheer loneliness children (and parents) can feel at this point in their lives. Sam is a true, genuine outsider. He partakes in social functions and rituals seemingly out of a duty to…well, be normal. That is not to say he’s a sociopath, or devoid of emotion. More that he honestly has no idea how to connect with others. It’s a deeply tragic path to watch him walk, and more than once the viewer will find themselves cringing at his behavior. Adults, from his point of view, rarely have his best intentions in mind, be it an abusive foster father or a creepy possible pedophilic foster uncle. To Sam, adults are the others, not him, and rarely in the film are any of them cast in a benevolent light.

The most impressive thing about this film is how, despite being such a weird individual, Sam is still not just wholly sympathetic but also somehow deeply relatable. Even if you yourself weren’t like that at his age, you knew someone like that: a person who radiated strangeness and loneliness in equal parts. Newcomer Mirko Giannini, in an absolutely stunning debut, embodies Sam not just with an off-putting oddness, but also with a naïve curiosity about the world, a sweetness that strikes a paternal note in those around him, including the viewer. The image of a black lamb in the closing sequence could come off as a bit on the nose but I found it to be the perfect symbol for what Sam is: the cuddly version of the outsider, weird but vulnerable.

Astrakan is a straightforward depiction of how difficult growing up can be, and it is an exercise in empathy when it comes to how we view the protagonist Sam. For everything that happens in this film, Depesseville is simply asking us to try and relate to Sam, despite all his various unusual behaviors, and understand he’s simply a child trying to navigate a safe path to adulthood but finding it difficult to do so. There are moments in this film that will make the viewer wince and recoil, but in the end this shrinking away from it helps us understand what’s going on in Sam’s bizarre little brain, and if you can sit through the somewhat vulgar moments, it’s an incredibly beautiful film that gives voices to the weirdos of the world.