In The Printed Screen, I’ll be taking an irreverent look at comic book adaptations of notable films. Some of these were released at around the same time as their film counterpart, with the comic being based on an initial script and/or concept art, while others came out months or years after the fact. I’ll break down notable differences, look at the advantages and limitations of comic books compared to celluloid, and try to look at the broader context that led to the creation of both works.

The big bang for superhero movies occurred in 1989 with Tim Burton’s Batman.

Stay with me for moment.

Yeah, I know there were plenty of superhero films before 1989. Don’t rush me. There were the Captain Marvel, Batman and Captain America serials of the 1940s, the Superman radio and TV show of the ’50s, the El Santo lucha libre films of the ’60s and ’70s, the tokusatsu films of Japan and a whole slew of campy films and television shows inspired by the ’60s Batman series. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

But nothing really prepared audiences for Richard Donner’s Superman in 1978.

But while Superman was a high water mark for the adaptation of comic book superheroics to the silver screen, it didn’t exactly kick off a flurry of cinematic imitators. It was simply too costly to try and replicate that scale and level of special effects, so while there were a few superhero movies that came in Superman‘s wake, most of the comic action was relegated to the small screen on shows like Wonder Woman, The Incredible Hulk (and its various TV-movie followups) and the short lived Amazing Spider-Man series.

And let’s not forget shows not actually based on existing franchises such as The Greatest American Hero, Automan and Manimal. Yeah, TV can get weird.

Burton’s Batman changed all that. It established that audiences would accept even the most ridiculous elements of a comic book origin (for instance: dressing like a freaking bat) as long as it was presented with a distinct style. It also established that superheroes could mean huge business. Not just at the box office, where Batman reigned supreme for months, but also with the awe-inspiring marketing campaign that came along with it. If you lived through 1989, you’ll remember that the Batman symbol was absolutely everywhere. From shirts, to cereal, to Chef Boyardee, Batman was the guy to beat.

And that’s why I’m here to talk about Batman.

Wait, what? I’m not here to talk about Batman? How embarrassing. Well, the thing is, while superheroes were obviously money in the wake of Batman‘s huge success, it didn’t lead to an immediate slew of comic book adaptations from DC and Marvel. While the comics industry as a whole was hitting extraordinary highs (that would soon lead to unbelievable lows), DC/Warner Brothers seemed happy to focus on a Batman followup from Burton, as well as a Flash TV series that completely ripped off Burton’s Batman aesthetic, and eventually a Batman animated series that took Burton’s ultra-stylized art deco look (and Danny Elfman’s score) even further. They basically just wanted to keep doing what worked until it no longer did.

Marvel was suffering from financial difficulties at the time, and while they had a slew of recognizable characters, they had optioned the film rights to smaller production and releasing companies, leading to the disastrous 1990 Captain America adaptation by Albert Pyun, as well as the even more disastrous Fantastic Four adaptation in 1994, which I don’t have time to cover here. Go watch the documentary.

There was even an aborted attempt by Cannon films to make a Spider-Man film directed by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre‘s Tobe Hooper before they finally went under. Just imagine living in the world where that happened.

Anyway, studios wanted superheroes, but they didn’t necessarily want the massive special effects budgets (or huge licensing fees) that came with them. So they decided to instead go back to the pulp heroes of the early 1900s, which eventually would lead to middling adaptations of 1930s characters like The Shadow and The Phantom (created by Lee Falk in 1936), both of which were figures with an enduring and popular legacy that were pretty much unknown to kids of the ’90s who just wanted to see how many pouches Rob Liefeld could fit onto a character’s belt.

When Batman was released in 1989, Sam Raimi was hot off of the success of Evil Dead 2, and was looking for a project that would break him in Hollywood. He was actually in the running for the Batman directing gig, and even pitched an aborted adaptation of The Shadow, but eventually he made a deal with Universal to bring to life a character from an earlier short story of his that was equal parts pulp hero and tormented monster, but with a visual style clearly influenced by Tim Burton’s take on Gotham City.

And it turned out really well.

What, were you expecting a review? That’s not what this is. But I’ll just say that Darkman is a whole lot of fun, thanks to Raimi’s kinetic visual style and Liam Neeson’s unhinged lead performance. It’s also unbelievably dark, leaning even more heavily into horror than Burton’s PG-13 Batman adaptation. There’s a lot of iffy rear projection work, particularly in the climax, but it’s action-packed and features a great supporting turn by the late Larry Drake as Robert G. Durant.

And it also features a score by Danny Elfman, in case you weren’t quite sold on that “inspired by Batman” thing.

But what is most pertinent here is that Marvel comics released a three issue adaptation of Darkman starting in October of 1990 (the film was released in the US and Canada on August 24th) written by long-time Marvel editor Ralph Macchio (not that one), and penciled by the prolific Bob Hall.

These three issues were published monthly in color, but Marvel also released a magazine-style black and white version, collecting all three issues into one volume. That version also features a particularly gruesome — and awesome — cover by Joe Jusko.

Both film and adaptation start similarly, with Robert G. Durant and his hired goons meeting a gangster named Eddie Black by a pier, regarding Durant’s recent efforts to muscle in on Black’s criminal dealings. Durant’s crew slaughters Black’s men thanks to one of Durant’s thugs replacing his wooden leg with a machine gun, and it ends with Durant threatening Black with a cigar cutter. As you might expect, the action in the comic (which runs a brief 68 pages) is much more compact than the film version, but there is an interesting switch in a piece of Black’s dialogue.

Weird, right? Well, unsurprisingly, according to the film’s script the original line was:

And in case you’re thinking this was all in an attempt to get a precious PG-13 rating…you may be right, except Darkman ended up rated R anyway. Of the three versions, I think I prefer “crumbs,” though “dinks” gets points for originality.

After some opening credits, the film (and comic) then transfer to the lab of Peyton Westlake, where he and his assistant Yakitito are working on the synthetic skin that will be at the center of the film’s face-swapping gimmick. The pair are having some issues getting the skin cells to remain stable past the 99-minute mark.

But while the movie version of Yakitito just happens to be a scientist of (presumably) Japanese ethnicity, with no perceivable accent, the comic decides to go all-in on presenting him as a grotesque Mickey-Rooney-in-Breakfast-At-Tiffany’s stereotype, complete with big, round glasses and buck teeth.

But blame shouldn’t go entirely to Macchio and Hall, as this is a paraphrased version of the line from the original script, which also presented Yakitito in more unpleasant terms (which I can only hope was meant to be a misguided tribute to the insensitive portrayals of the characters that tended to assist classic pulp heroes). The script even describes him as wearing “thick, coke bottle lenses,” so there you go.

Sliced out of the film here is a lengthy sequence in the script (and comic) where Louis Strack Jr. (the film’s corporate villain) witnesses his father’s murder in the street. There seems to be more of an effort to try and hide Strack’s true malevolence in the comic, something the movie plays with briefly, but come on. We know he’s a dick. Look at that suit!

The following scenes establish Westlake’s relationship with his long-time girlfriend Julie, he struggling to propose to her, and she (nicely) blowing him off to confront Strack with an incriminating memo, and they play out quite similarly to the movie.

That brings us to Westlake’s eureka moment, where he and Yakitito discover that keeping the liquid skin in darkness will allow it to break the 99 minute barrier. Just as they are about to celebrate their victory, they are accosted by Durant and his flunkies who proceed to trash the lab and…ventilate poor Yakitito.

The gang beat up Westlake, smashing his face into a whole buncha glass, which is played for much more dark humor in the film than in the comic, where it’s a bit more gruesome.

This might be a good opportunity to briefly discuss the comic’s version of Robert J. Durant, the cigar chomping, finger-slicing antagonist of Darkman (as well as Darkman II: The Return of Durant). While Larry Drake’s slightly effete performance (and unique visage) brings some campy life to the character, the comic book version is awfully generic.

Who is that? Tommy Lee Jones, maybe? Or one of the lead characters from River City Ransom? It’s certainly not Dr. Giggles.

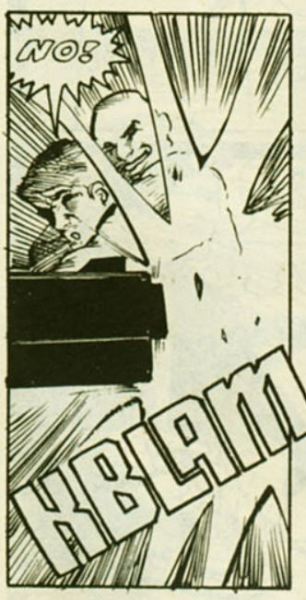

So, with the help of one of those plastic drinking birds, Durant and the Boyz blow up Westlake’s lab (along with Westlake). This is shown in a tremendous half page image which implements both a terrific sound effect noise (WHA-BOOOOMM!) as well as Westlake’s mournful cry of “NNNNOOOOOOOOO!”.

Compare and contrast with the film’s version:

Where Westlake/Neeson makes more of a “WAAAAUGHHHHH” sound. Both are very valid responses to being blown up real good.

It’s interesting to note that the comic makes little attempt to capture the unique camerawork and editing of the film. This is particularly notable in one of the film’s most memorable (and comic book-y) edits, where the shocked Julie (who had witnessed the explosion from the street) is impressively faded into a mourning version of herself at Westlake’s grave. Another suggestion that Macchio and Hall were exclusively working from the script.

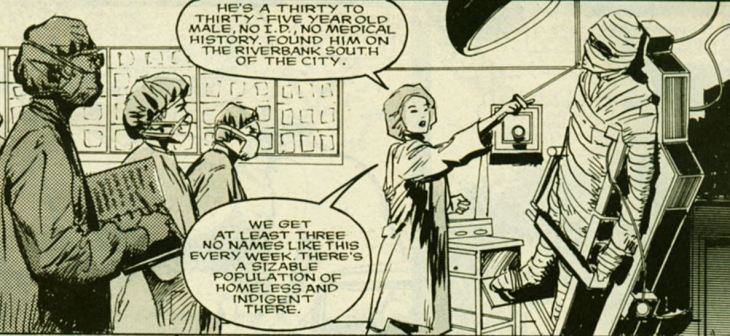

So, Westlake’s almost-dead (and very burned) body is pulled out of the river and brought to Los Angeles general hospital, where the nerves that would normally be leaving him screaming in pain have been severed. Apparently a side-effect of this is that it leaves the patient emotional and irritable, as well as sending adrenaline coursing through their body. Yes, being blown up by gangsters has left Westlake super strong, near-invulnerable and emotionally broken.

In the film, the burn doctor in this sequence is played by An American Werewolf in London‘s Jenny Agutter, while Ivan Raimi and Werewolf‘s director John Landis (post Twilight Zone: The Movie involuntary manslaughter trial) play two of the doctors looking on. See? I’m full of fun facts.

Westlake, covered in bandages, escapes from the hospital and finds some abandoned clothes (including a stylish hat) in a filthy alley. Disoriented, he attempts to track down Julie, who (understandably) mistakes him for an insane person covered in bandages and wearing filthy alley clothes. In the film, he just sort of mumbles nonsense at her, while in the comic he, uh..

Distraught, Westlake goes back to the ruins of his laboratory, where he has a few realizations.

a) His work has pretty much been completely destroyed.

b) His face and body have been fucked up beyond recognition.

c) Julie will never accept him since he’s so ugly and weird looking

d) SOMEONE HAS TO PAY.

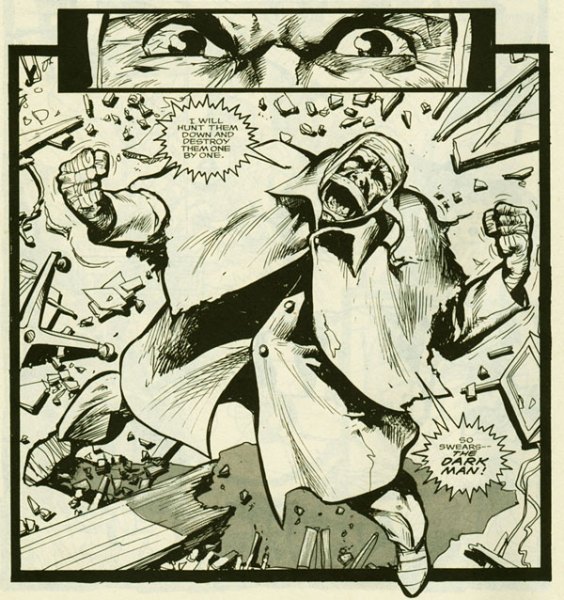

And he pretty much has a complete mental breakdown where he starts screaming about his wrath and what-not. This is presented in a really nifty full page image, which also includes some just-about-nude pics of Julie for some reason. She even has one of those Cable eyeball blinkies going on. It was the ’90s!

Now, in the film he just cries a bit and then heads into one of those abandoned locations that only exist in movies in order to rebuild his lab. However, the original script gives this entire sequence a bit more significance, marking it as the official arrival of Darkman. We know this because the script says:

Which is notable, because despite the film’s title, I don’t believe Westlake actually ever refers to himself as Darkman in the dialogue. I mean, why would he? Well, it appears that Macchio thought that Westlake’s rebirth needed a bit of extra oomph, which leads to this:

Tremendous.

Let’s stop here for now, but when we return we’ll take a closer look at Darkman as he takes his HORRIFYING revenge on Durant and his crew. Join us, won’t you? So swears— THE DARK MAN!