Welcome to THIS JUSTIN, a column dedicated to my love of all things weird and spooky. Each week I’ll be taking you on a deep dive into something creepy and/or crawly and talking your ear off about why I love it so much. Spoilers ahead!

The history of horror literature in America can be broken down into three eras, each defined by the author who had the greatest impact in that era. First, we have Edgar Allen Poe — who ushered in an era of short stories and whose voice would be heard into the next century. Then, H.P. Lovecraft — who moved horror out of the gothic realm, with its crumbling castles and haunted mansions, into a vast and hostile cosmos. A world where humanity was but a small speck on an island adrift in a universe amongst universes, all, at best, apathetic to our fates. Finally, since the mid 1970s, Stephen King has held the unquestionable title of titan of American horror literature. For four and half decades, King has brought horror literature into American pop culture, with his some of his books being turned into some of the greatest films of all time. He is undeniably the face of horror literature to the world and his name is synonymous with all things weird and spooky.

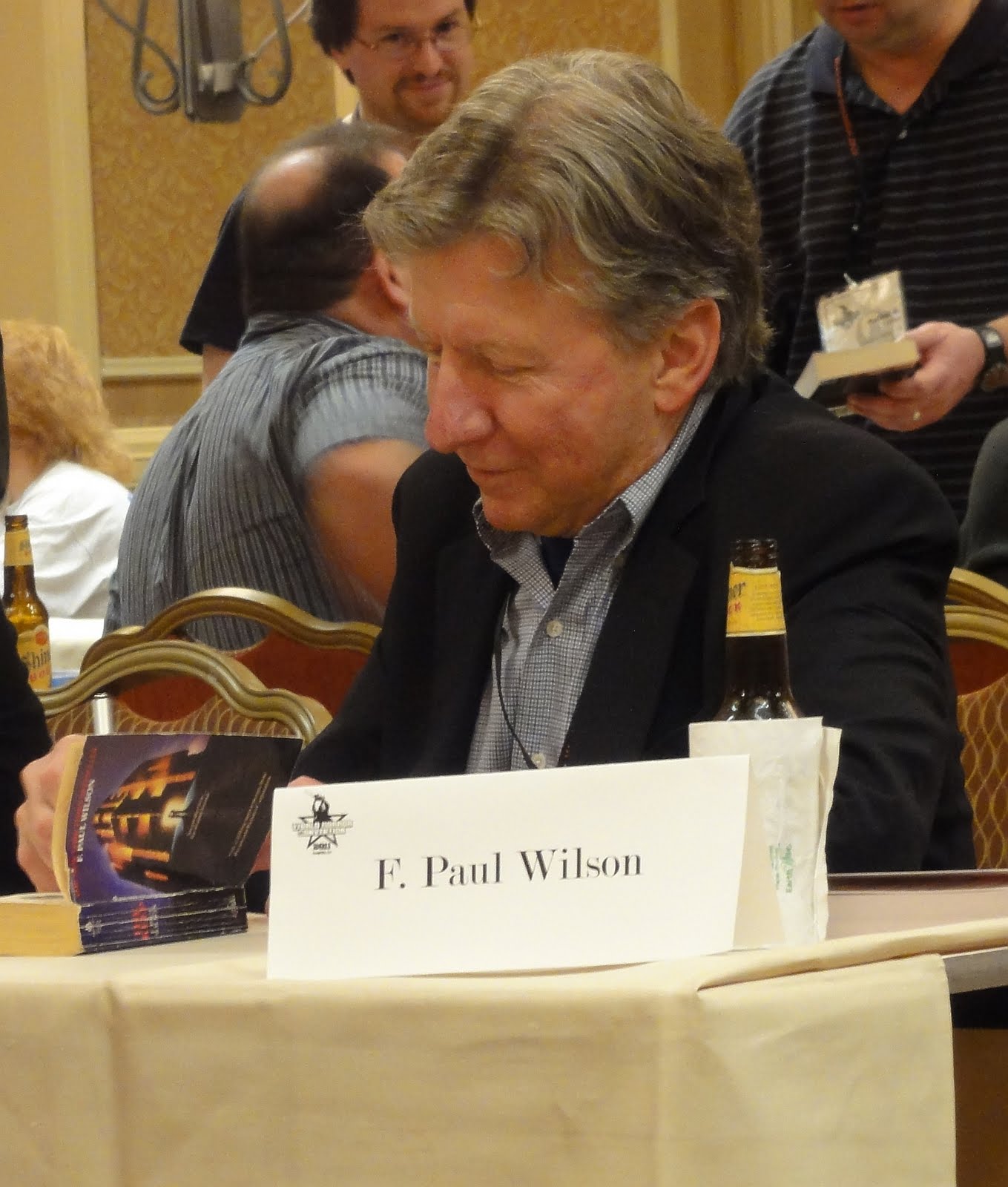

However, it is not King who is the heir to the throne of Lovecraftian cosmic horror. To be fair, King owes a great debt to Lovecraft: not only does he pepper his works with references to Lovecraft, but also utilizes many of the same devices that were signature Lovecraft techniques. He writes about seemingly idyllic towns with seedy histories, of extra-dimensional horrors so ghastly in appearance the human mind cannot comprehend their true from without shattering into madness, and of our reality being just part of a greater whole. But there is another who writer out there who manages to out-Lovecraft King, who utilizes many of Lovecraft’s themes to tell his own stories, and even manages to fix some of the biggest problems with Lovecraft’s fiction. And I don’t mean just tentacles, fish people, and thinly-veiled racism; more so the…quieter themes of Lovecraft’s work. The less slimy, less tentacle-y, racist themes that Howard Phillips Lovecraft dove into. That writer is F. Paul Wilson.

To many cinephiles, Wilson’s name may immediately bring to mind the 1983 Michael Mann adaption of his novel, The Keep (which we discussed on Horror Business); but Mann’s vision falls short of capturing the true spirit of the novel. Wilson’s fiction is more than a bizarre quasi-psychedelic sword and sorcery vehicle for Scott Glenn, soaked in the lush tones of Tangerine Dream. Rather, it is a constantly growing (albeit at a much slower pace these days) narrative that draws very heavily on some of the basic themes that Lovecraft was fond of exploring.

First, a primer. Wilson’s most popular collection of work centers upon the breathtakingly vast Secret History Of The World, a narrative than can be broken down into two main branches that eventually merge: the Adversary Cycle, a series of six books spanning from The Keep in 1981 up to conclusion of the series in with 1992’s Nightworld; and the Repairman Jack saga, which began with The Tomb in 1984 and wrapped up in 2011 with The Dark At The End before merging with a heavily revised and updated version of Nightworld. There are several short stories, novellas, and even a prequel trilogy for Repairman Jack that further flesh out the Secret History, but those two branches make up the bulk of the story. The focal point of the Secret History is what became known as The Conflict.

Since the beginning of time, throughout all existence, there have been two vast opposing forces battling one another. Not just within our reality, but every single reality. One, known as The Otherness, thrives on misery and pain and view sentient worlds as a food source. The more suffering it can cause, the more sustenance it can derive from it. The second force, known as The Ally, collects sentient worlds and opposes the Otherness at every turn. These two powers have been using lesser beings as pawns throughout existence, and to the Ally this game is just that: a game. The Otherness has a little more invested in the battle, but overall each individual world is little more than another piece of meat. Several thousand years ago, before recorded civilization, the rise of sentience on Earth caught the attention of these two powers and the battle came here, beginning the Secret History. Leading the forces of the Ally is an aged curmudgeon named Glaeken, a millennia old warrior who is weary of life and only wishes to die peacefully. His counterpart for the Otherness is Rasalom, a man changed by his allegiance to that dark power into something inhuman. Their conflict on Earth represents the Conflict as a whole, and Wilson drops us into the middle of it with The Keep and develops the story with every novel, novella, and short story in the Secret History.

Obviously the first comparison to Lovecraft is the relationship between humanity and some higher powers. Wilson’s Ally and Otherness could easily be Lovecraft’s Elder Gods and Great Old Ones aside from one key difference: Lovecraft stressed that his godlike entities were so unknowable and alien to us that their motives could never be known; that they’re not necessarily evil so much as completely incomprehensible to us. Wilson, on the other hand, removes any doubt as to the motives of his creations: they want us. This planet. This section of reality. Everything that exists. But instead of using the “good vs. evil” cliché, Wilson leans even further into Lovecraftian territory by making the “good” force not so much a friend but merely a barely interested, if not benignly negligent, party that wants to keep what it has to itself. Like a person who collects records, the Ally doesn’t really need to protect us; it just likes having us as part of its collection. And, much the same as a record collector wouldn’t really mourn the loss of an average collectible record, the Ally doesn’t really put too much thought into our existence unless it’s under a dire threat. Even then it’s barely aware of us. The Otherness, though, needs us. In the realm of the Secret History Of The World, the only thing keeping an immensely monstrous power from turning us into hors d’oeuvres is an equally opposing power who is just involved enough to keep it from taking over. With this dynamic, Wilson has injected real stakes into his narrative and made the story weirdly human, especially since his main characters are normal people who are all direct targets, while the powers serve more as backdrops.

Much of the story is seen from the point of view of Jack, a fixer in New York City who has dropped off the grid and makes a living by doing dirty work no one else is willing to do. He’s a likeable everyman, relatable in every way; the guy you have a good time with but don’t really think too much about until you bump into him at a bar or coffeeshop. Suddenly, he finds himself smack dab in the middle of this cosmic conflict. These powers, it is revealed, have shaped his entire existence. So to Jack, as well as the reader, this is intensely personal. The Conflict is affecting the lives of characters we come to care very deeply about. The tremendously wide scope of the Conflict is still there, but the best parts of Wilson’s stories happen when it’s shown how a relatively normal person would deal with being confronted by the monstrously abnormal. Sure, it’s terrifying in some of the books when there’s talk of tearing open the veil that separates this reality from the Otherness and ushering in “monstrously dark times” for the entire world, but the most heart-wrenching and horrific parts happen when the characters we invest ourselves in are directly threatened. Too many times to count, Jack’s friends and family not only come close to death but are abruptly and gruesomely removed from his life by both side of the conflict. Wilson’s ratcheting up of personal tragedy, and the focus on how his characters react to such tragedy, injects a humanity into Lovecraftian fiction that was desperately needed to keep the genre grounded, while at the same time showing how truly alien the participants in the Conflict really are. It’s a brilliant narrative technique, like adding a dash of coffee to a chocolate cake to make the sweetness of the chocolate stand out even more.

In that same vein, it’s worth noting another key difference between Wilson and Lovecraft is the attitude towards humanity’s relation to the Conflict. For Lovecraft, human concerns were ultimately meaningless in the face of his vast cosmic entities, and his stories always carried more than a tinge of nihilism. Wilson also grants that human affairs ultimately mean next to nothing, if anything at all, to both the Otherness and the Ally. But they are still given emotional weight because to the characters themselves they mean everything. The death of Jack’s family members might be little more than something like a sharpening a knife or cleaning a gun to the Ally, a mundane task meant to keep a weapon in perfect killing condition. But to Jack, it’s everything. When it’s eventually revealed his entire life has been nothing more than a glorified “break glass in case of emergency” routine for the Ally, he’s enraged and devastated. And rightfully so. Even though we as the reader understand the motivations of the forces making these choices, we are seeing this from Jack’s point of view. We understand that no matter what higher powers decide, and no matter that the Ally’s choices are done for the greater good, Jack’s outrage and frustration and anger are still valid. As mundane as it may seem to these powers, his life is still his.

The very name of this saga, the “Secret History of The World,” draws heavily from the fiction of Lovecraft and his mythos. Lovecraft and his circle were obsessed with the idea that the age of man and all of recorded history represents but a sliver of actual history. The Lovecraft mythos is peppered with tales of lost civilizations, forsaken continents, and islands that were swallowed up by the sea. From the Plateau of Leng to Robert Howard’s Hyperborea, the Cthulu Mythos has an entire forgotten geography to draw from. Wilson’s version of a lost civilization is not as deeply fleshed out but is no less important. For Wilson, the lore of this unnamed civilization becomes more and more important the further the series extends, especially once it becomes clear that there are still powers from that civilization that are shaping current world events. In one book Jack finds out that a cult of self-mutilating cenobitic priests plan on using a weapon created eons ago by the Otherness to inflict mass casualties on New York City. Early on in the series Jack comes across a fraternal order that at first seems like nothing more than a fancier version of the Freemasons. In reality, they are the remnants of a secret society led by a council of mages who worshipped the Otherness thousands of years ago prior to the cataclysm that wiped out that civilization. Relics, weapons, forbidden books, personalities, and monsters from Wilson’s “First Age” are featured heavily in the Secret History. Even Lovecraft’s shittiest feature of his fiction, his virulent and unrepentant racism which often took the form of his fear of “miscegeny” is turned on its head. We eventually find out that there is literally only a single human being in the world who is entirely free of a bloodline that comes from the Otherness itself. In other words, in Wilson’s world we are all the mongrels and half-breeds and mulattos that Lovecraft was so terrified of. Wilson effectively takes the idea of some “Other” (quite literally naming his main villain “The Otherness”) and strips it of Lovecraft’s racism by extending it to all but one person on the face of the planet but still maintains the unsettling concept of having something alien present in all of us.

The failure of classical science in the face of the inexplicable was a trademark of Lovecraft’s fiction. It was presented as at best neutered and insufficient and at worse actively evil. The most well known example of science failing would be Lovecraft’s concept of “non-Euclidean geometry.” Modern geometrical theory does actually have a field known as non-Euclidean geometry, but Lovecraft’s use of the term was meant to be more paradoxical and fantastic, something so alien and strange it drove those who tried to perceive it into madness. He writes of impossible colors and strange formulae, weird angles and weirder biology. Science as an evil is represented by characters such as Crawford Tillengast and Herbert West; men who dared defy the “normal” realms of physics and chose to tread unexplored territory and inevitably brought their own doom upon themselves. In these cases, scientists are cast as Promethean lunatics, madmen who sought knowledge for knowledge sake no matter what the cost.

Wilson’s work uses the same approach to science as well. A hallmark of the Repairman Jack saga and that nature of the Otherness is that it defies rationalization and reasoning, remaining chaotic and unknowable despite the best attempts at doing so. The simple concept of “possibility” is mocked to inject a quiet sense of discord into the overall narrative. The impossible becomes routine. In Conspiracies, the idea of Occam’s Razor is discussed at length in regard to modern conspiratorial thought and then wholly defanged when the truth of the matter is revealed. All The Rage features a molecule that at the onset of the new moon every 29 days changes structure like clockwork. All representations of the molecules, be it a model, photograph, drawing, and even memory, change as well. In Bloodlines a geneticist discovers that hidden within the so-called “junk” DNA of the human race are the remnants of another species of human that shouldn’t technically exist. In Nightworld, the climax of the Secret History, literal bottomless holes open all over the globe, and Glaeken describes the world upon Rasalom’s ascension as one lacking in any sort of order whatsoever. The laws of physics, astronomy, thermodynamics, and even time itself are reduced to “futile meaningless formulae” as the Otherness de-shapes our reality.

Science as an active evil is also present in Wilson’s work. In Hosts, a scientist attempting to perfect a new method of therapy for brain tumors inadvertently creates a virus that becomes the perfect tool to sow chaos and mayhem. In The Last Christmas, a breakthrough involving stem cell research leads to the creation of a miserable human-wolf hybrid that ends up becoming an unlikely ally. Again in All The Rage, a pharmaceutical company trying to patent a new drug ends up synthesizing something that turns docile people into raging lunatics. In Reborn, we find out that a secret WWII-era project attempting to clone a human being is what allows a defeated Rasalom to be reborn. And in Wardenclyffe, Tesla’s research into broadcast energy is revealed to have nearly ended the world in the early 20th century by weakening the veil between this reality and the Otherness. In other words, sometimes science shines a light where light ought not to be shown, and sometimes that light not only fails to illuminate the darkness but lets what’s in the darkness know we’re here.

Many of Wilson’s characters, usually compatriots of Repairman Jack, are portrayed as bright and sharp individuals facing something that defies explanation. Not necessarily something monstrous or hideous, but just something inexplicable. More than once, the idea of something being “good” or “right” is conflated with the concept of something being “reasonable” or “true.” Likewise, natural vs. unnatural are often used synonymously with right and wrong. None of this is to say Wilson is an anti-intellectual; far from it. Jack is shown to have attended school as an English major before dropping out, possesses something of an encyclopedic knowledge of old films, and frequently identifies some of the characters he meets in terms of characters from classic literature and film. In The Haunted Air, we’re introduced to Lyle Kenton, a talented “medium” who uses his powers of observation to make his way in the world by convincing people he has access to a channel into the afterlife. At one point, it’s revealed that while Lyle never formally attended college he would often sit in on any lecture he could to learn for learning’s sake. To be fair, a higher education is often portrayed in the books in a rather Baby Boomer-esque way; Wilson can hardly be blamed for doing so. It’s important to note that Wilson is not mocking science or intellectualism. There’s no sense of disdain for intelligence. Like Lovecraft, Wilson simply understands the concept that what can be truly frightening is an inability to discern order from chaos. In the words of his big-bad Rasalom, “the human mind finds comfort in patterns: I shall offer none.” In other words, sometimes that which cannot be grasped, defined, explained, or rationalized is the most terrifying thing of all.

Lovecraft’s views on race are…well documented. That is to say it’s no secret he held great disdain for other ethnicities. He was, at best, an unapologetic and enthusiastic Anglophile and at worst (and most likely) a rabid white supremacist. The argument has been made that you cannot judge the work of someone by their own personal views, but even his work is clouded with his views on race. There has been a meme circulating about the name of Lovecraft’s cat (I won’t say it, just Google it) which was also the name of a cat one of his characters had. He also once wrote a poem entitled “On The Origin Of The [expletive term for a person of color]” so there’s that. Lovecraft’s racism was layered and academic, steeped in pseudoscience and rooted in arcane views on human origins, and that racism certainly leaked into his work. His stories are littered with mentions of “half breeds” and “mulattos”, none of whom are ever up to any good. People of color are described as sinister Orientals and hideous Negroes. Even some of his most famous stories revolve around the concept of interspecies breeding. The protagonists of “The Dunwich Horror” are the spawn of a human woman and Yog Sothoth, one of the many deities in the Cthulu Mythos. The citizens in the titular town of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” were the result of breeding between humans and a race of amphibious fish people known as the Deep Ones. Clearly, Lovecraft was horrified the thought of “impure blood” and non-white ethnicities. He looked upon the ethnic spectrum and saw the diversity and non-whiteness as a source of horror. Wilson, on the other hand, did away with such racism. His Secret History is filled with characters from across the racial, religious, and gender spectrum. Repairman Jack’s friends are a hodgepodge of races including a Jewish gunshop owner, a Hispanic barkeep fiercely loyal to Jack, two brothers of African descent, and a gay hairdresser who is deceptively able to defend himself. Wilson often highlights the ignorance of assuming all Muslims are jihadi terrorists or that all brown people who wear turbans are Muslims. While some of the early chapters of his work use the planners of the 1993 WTC bombing as villains, in a later novel Jack becomes a defender of a Muslim man desperate to save his family from a raving Islamaphobe. In Wardenclyffe, our narrator is a transgender man terrified of what would happen to his career should people find out his gender assigned at birth. As for the concept of impure bloodlines, Wilson reveals that literally every single person on Earth, save one, has some lingering horror lurking in their DNA; remnants of an ancient cataclysm involving human beings who had been tainted by the Otherness. Wilson clearly understands the concept of diversity, but unlike Lovecraft doesn’t see it as a thing of horror but rather a quality of existence. There’s no sense of tokenism in his work; Jack lives in New York City so it only makes sense that his friends consist of all types. His characters are not cardboard cutouts or archetypes of races. This is not to say Wilson is some kind of virtue-signaling uber ally touting the greatness of political correctness, or a champion of “wokeness”; I actually suspect personally he detests such mindsets. It’s more that he simply recognizes the world for what it is and instead of bemoaning diversity celebrates it as a natural aspect of how things are and incorporates that into his work.

I think the final improvement Wilson makes on the Lovecraft mythos is on the depictions of morality and human nature. Both writers wrote of a universe in which the Judeo-Christian god does not exist and is instead replaced with entities that are largely unknowable and deeply alien to humanity. Whereas Lovecraft infused his work with a brand of cosmic nihilism and amorality, Wilson chooses to highlight a basic goodness in humankind. His morality (typically depicted through Jack or Jack’s predecessor Mr. Veillur) is simple but not saccharine. Instead of originating from the command of a higher deity through religion, it hinges upon the simple concept of: do the right thing, no matter what. It’s a vaguely Kantian concept that stands in stark contrast to the cold utilitarian and strictly functionality “morality” the players of The Conflict exist by. Countless times throughout his story, Jack exhibits an innate goodness, doing good for goodness’ sake. His word is bond, so to speak, and he keeps it no matter what. When an old flame attempts to seduce him and justifies it by telling him his longtime partner would never know, Jack simply points out that he would know. His adherence to morality exists devoid of consequences; the outcome of any one act didn’t define the rightness or wrongness; the act itself did.

Once again, though, Wilson’s Secret History traces a thread back to Lovecraft in the concept of good and evil. At one point, Jack remarks that once he was sure that humanity was the only source of good and evil in the universe; and while he was still certain we were the only source of good, he was equally certain that there was an external evil impinging its will upon us, i.e. the Otherness. While both writers’ works feature characters that are haunted by a glimpse behind the veil, so to speak, most of Wilson’s characters are genuinely good people whereas Lovecraft’s are often not. Peppered through the books are moments when true human goodness shines through in a very sincere way, instead of a string of broken and haunted people who cannot deal with what they’ve witnessed. That is not to say Wilson’s character’s aren’t broken or changed or haunted by what they’ve seen; a lot of them are. But despite being a series so deeply steeped in paranoia and terror, the Secret History Of The World is quite optimistic on human nature. Much of the penultimate volume of the Secret History, Reprisal, revolves around a debate on the nature of morality, altruism, and the social contract. When the villain of the book attempts to sway a central character to a philosophy of elite selfishness, Wilson’s protagonist and hero Will Ryerson repeatedly argues in favor of a “we’re all in this together” style morality; instead of every man for himself, it’s no man left behind. Such clear-cut examples of goodness in the face of vast chaotic cosmic evil are a refreshing change from Lovecraft’s drab cosmic nihilism.

For better or for worse, Howard Phillips Lovecraft casts a great shadow over the horror genre. Without him, we wouldn’t have arguably the most popular horror writer of all time; a man whose work shaped one of the most important decades in modern pop culture (read more about that here). But while Lovecraft may have shaped the work of Stephen King and laid the groundwork for King’s emergence into the realm of horror fiction, it is not Stephen King who inherited the lunatic throne of Lovecraft’s style. F. Paul Wilson took Lovecraft’s basic ideas and expanded upon them, polished the rough edges, fleshed them out into relatable stories, and patched up some of the, shall we say, weak areas of his work. It is Wilson that carries the legacy of Lovecraft into the 21st century and wields the banner of the champion of weird fiction in horror literature, all the while retaining a distinct style of his own. He takes Lovecraft’s odd sensibilities and makes them palatable to a wider audience while still maintaining the essential strangeness that made HPL so groundbreaking.

6 Comments

Manuel López

Fantastic piece! Still, to be honest, my mind is reeling frantically trying to remember if I had read anything by Wilson. If not, I will surely remedy that. (It happens often, one of my favorite novellas, The Skin Trade, was writen by a guy whose name I could never remember, until I had strong reasons to do so: it’s George R. R. Martin).

Lovecraft came to my reading life a little late, of course he has become one of my patron saints as an aspiring writer. Uh, yeah, Horror, of course. And naturally, his work blew my mind. And yes, I noticed the racist and xenophobic fragments, but of course, he was not only a man of his age, but one stuck in a time before his age.

Anyway, I loved this piece, and it has made me want to read the work of F. Paul Wilson. When this happens, it’s always something good. Having read mostly short stories by S. King, I used to dismiss him as “too teenage oriented”. A friend of mine convinced me to read “Firestarter”. King is a role model now, as you may deduct.

So, thank you, Justin.

James Reyome

My goodness, if this doesn’t convince you to read TSHOTW, I don’t know what will. Do yourselves a favor though and go to Wilson’s website at repairmanjack.com and check out the list in order. Also, don’t ignore the “Jack” young adult books, which fill in a lot of pertinent details.

Seriously, I envy anyone reading the series from the beginning for the first time. It is a treat from start to (?) finish. Enjoy!

Todd Nesbitt

Hey Justin, thanks for the great article. I’ve read some Lovecraft but found him a little too nihilistic for my tastes. I was a lot younger though so I may give his work another try. I have never read Wilson but his series sounds very interesting and right up my alley. I am going to give ‘The Otherness’ series a go. Thanks again for the great info!

Todd

A.J. Bajek

Bravo! This was an unbelievably well written piece! I have said for years the F Paul Wilson was not only the heir to Lovecraft but improved on his style and story telling for years. I just never said it as well as you. Excellent work!

Richard L.

I’ve been reading F. Paul Wilson since The Keep in 1981. He is truly one of the great and under-appreciated authors of his – and any other – era. Thank you for this fantastic article/analysis!

Justin Lore

Thank you for reading and responding!! It’s greatly appreciated.