“Doesn’t matter where you go in the world, everybody hates skateboards.”

This year is an important one for skateboarding, as the sport will officially debut at the COVID-delayed 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, opening July 23. While the skate community’s feelings about this are varied and complex, there’s a kind of affirmation inherent in this recognition, at least in the eyes of the world. The popularity of skateboarding has waxed and waned in turn over the course of decades, but thanks to pioneers who toiled for respect and validation while evolving skating as a hobby, sport, and artform, it’s largely come into a place of mainstream acceptance.

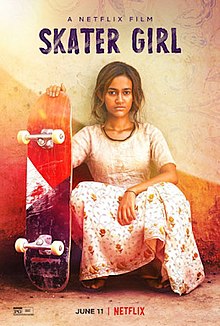

Skateboarding has roots in California, where surfers in the 50s and 60s devised methods for “sidewalk surfing” by affixing rudimentary trucks and wheels to small surfboards or other platforms. Today, it’s undeniably a global phenomenon with a passionate worldwide community. There is no one kind of skateboarder, but whether it’s performing tricks, bombing hills, carving bowls, or just cruising or longboarding to enjoy the ride, the joy and exhilaration of skating is universal, and the representation of that specific and beautiful idea is what I love most about the India-set film Skater Girl, which recently made its debut on Netflix.

Prerna (Rachel Saanchita Gupta), a teenage girl, and her younger brother Ankush are, aside from being among the poorest families in their village, fairly typical kids in rural Rajasthan, India. Their family’s poverty makes it hard for Prerna to attend school (they can’t even afford the requisite uniform), and her overbearing father is a traditional patriarch, set in his old-fashioned ways—especially with respect to a woman’s place.

Enter Jessica, a fashionable stranger who immediately stands out in the humble village. Jessica is an Indian-English woman who grew up in London, where she became a successful businesswoman. Restless, she has taken a spontaneous pilgrimage to her motherland in an attempt to connect with her roots, which present a sharp contrast to her wealth. She’s not sure what she’s looking for in her ancestral hometown, but what she finds is Prerna. A girl in search of herself, and frankly, in need of a bit of rebellion – and a school uniform, which Jessica happily provides. She is shocked that something as simple as a uniform could present such a life-defining problem for the girl, and the two become fast friends.

Most of the villagers are wary of the stranger in their midst, but the kids warm up to her almost immediately. Jessica’s friend Erick is a skater, and when the village kids are fascinated by his skateboard, she makes what will turn out to be an enormously fateful decision: a huge box arrives full of brand new boards for the kids, immediately igniting a new craze. The goodwill gesture has unintended consequences though. Jessica just wanted to inject a jolt of happiness into the poverty-stricken children’s lives, but the resulting hellraising and hookeying whips up a furious frenzy with parents, teachers, and officials, and “no skateboarding” signs soon spring up all over town. The challenge will be to give the kids their own space to skate.

This is Prerna’s story though, and my favorite part of the film is her journey as a skater. I’ve seen a fair few skateboarding movies, but they’re mostly about the culture, primarily as seen through American eyes, rather than what’s actually great about skating. By disassociating skating from skate culture (which, where movie representation is concerned, has mainly centered on angsty party boyz), and furthermore centering on a female protagonist, the film hones in on the universal skate experience instead. Prerna hides her hobby from her disapproving father, secretively smuggling her board around, in and out of the house. She finds her balance, learns to push, and experiences the joy of cruising. She uses her school’s computer to watch skate videos online. She experiences the universal apprehension of dropping in (descending a ramp or bowl from the top) for the first time. And on a secret excursion she experiences an injury, which is especially detrimental to her situation. Her dad is pissed enough that his son is skating, but his older daughter obsessing over a toy, participating in a boys’ sport, and damaging herself in the process is just too much for him.

Her verdict?

Skateboarding is the best thing that’s ever happened to her.

The film serves as a sharp commentary on aspects of Indian culture, challenging status quos, particularly caste-based social stratification and arranged marriages. A budding romance develops with Prerna and one of her schoolmates, but it seems doomed from the start. Even though they both take an interest in each other, he’s from a higher caste, and she’s being groomed to wed someone else against her will. Her marriage, her life, is merely a transaction. Love isn’t part of the equation.

There’s admittedly a bit of a white savior trope here as Jessica and Erick take on the poor kids as a pet project, so to speak. Jessica herself may not be “white,” but she is a rich outsider from London, and more importantly, seen as an outsider to the villagers. It’s a little gimmicky, but in service to the story it makes sense. The primary catalyst for the story is penniless rural children being given the opportunity to skate, and that doesn’t just happen without some outside intervention. To me, it enables the film to capture something pure and universal that I haven’t really seen shown in any movie before:

The joy of skateboarding.

Catch Skater Girl on Netflix.