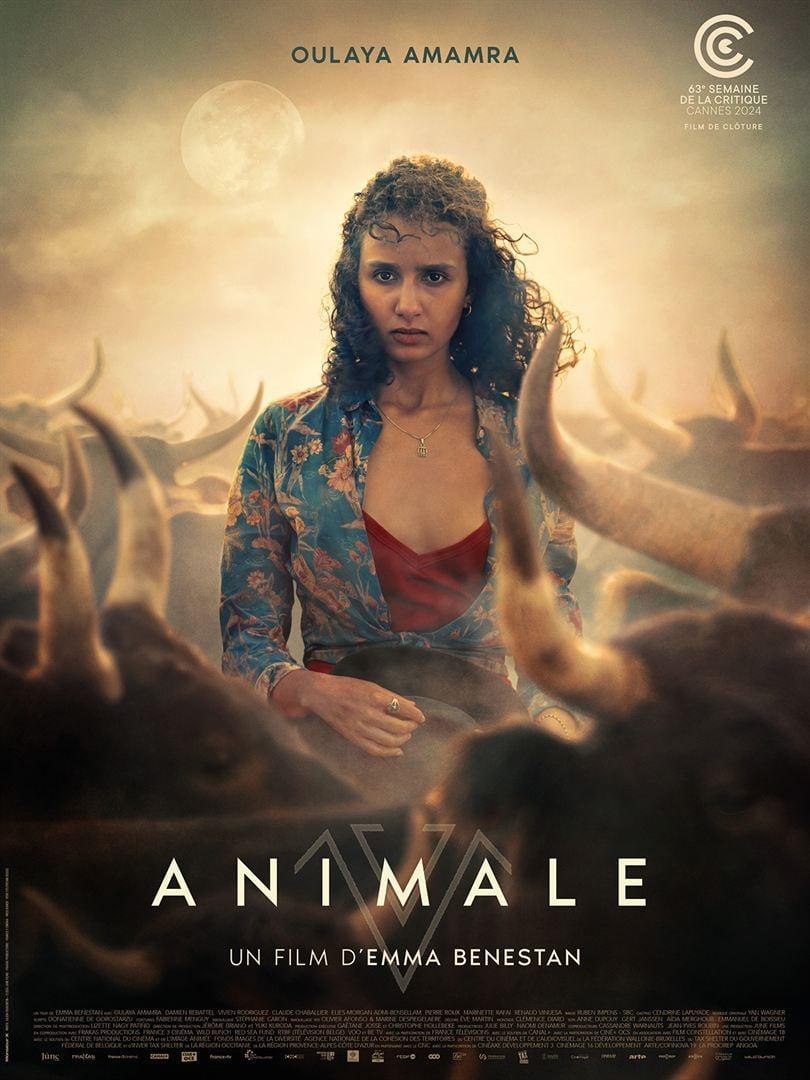

To quote poet Emma Lazarus: “until we are all free, we are none of us free”. In other words, until freedom is universal it simply isn’t universal. Emma Benestan’s Animale is an exploration of empathy, bodily autonomy, feminism, and good old-fashioned vengeance set against the bullfighting community in Camargue, France. Note: this piece is not an endorsement of the practice of any sort of bullfighting. Regardless of my opinion on the film itself, I am and always will be opposed to bullfighting in any form, no matter how “respectful” it is towards the animal. But that’s not a topic for a film review.

Nejma Chokri only wants one thing: to be a member of the elite bullfighting team in Camargue. Unlike traditional bullfighting, in which the bull is killed, Camargue bullfighting is more of an actual sport and the bull is not harmed. Contestants must pluck ribbons from the animals’ horns, all the while not getting gored/trampled/fucked up. The night after her debut match, Nejma is seemingly mauled by a rogue bull, although she has no memory of the event. Soon, her fellow team members start to die one by one, apparently at the hands (Hooves? Horns?) of a bull, and as Nejma begins to remember that night she becomes more and more sympathetic to the plight of the animals she’s working with and more and more angry at her surviving team members.

Off the top this is a beautiful film to witness unfold. The shots of the bulls at night in misty fields are somehow both gorgeous and terrifying, majestic, and not so subtly threatening. The cinematography does a lot to immerse the viewer in the experience, putting us in the ring with the bulls as they attempt to gore the fighters. As the film gets more and more fantastic, the camerawork successfully creates a feeling like it might all be a dream, a dark fairy tale that you could wake up from at any second. The ending only makes it feel even more like a fairy tale, a grim reminder of the consequences of our actions as well as the idea of “sometimes awful shit happens and it can’t be undone, even if those responsible are held accountable.” It is soaked in tragedy and violence, and this combination of the sublime and the horrific make it quite a treat.

Oulaya Amamra’s performance as Nejma absolutely propels this film past the finish line. Again: I’m not at all comfortable morally with any form of bullfighting, but Amamra sells us a character who actually does respect the bulls. Her discomfort at the little cruelties the other team members display towards the animals while branding them is powerfully relatable, and her outrage when one of them is unnecessarily slaughtered is heart wrenching. Her love for her favorite bull Thunder is very genuine and believable. All of this goes a long way towards us investing in her story emotionally and her arc being tremendously satisfying, regardless of the undeniable tragedy of that story.

While I might disagree with Benestan’s stance overall on the nature of bullfighting, I admire her attempt to make a comparison between the way these animals are treated and the way Nejma is treated. While Nejma herself might actually respect and love the bulls, her teammates see them (and her) merely as objects, trophies to be won in one game or another. To them, these animals are glorified sporting equipment Benestan makes a clear comparison in the casual objectification of these animals and the misogyny those same men display towards Nejma. It’s telling that the only men who seem to actually care for her are her closeted best friend and his elderly father, two men who for one reason or another don’t see her as a sexual object but instead as an actual human being. It’s also telling that they are the two most compassionate men in the film towards the bulls. It’s almost as if macho bullshit is a bad thing? Maybe?

Animale is a striking examination of the concept of understanding the pain of someone else and recognizing that pain, as well as a critique of toxic masculinity and the cruelty that comes from objectifying those we perceive as weaker than us. Benestan crafts a haunting film, visually lush and achingly lovely, that doesn’t ever seem interested in the comfort of the viewer but more in making the viewer feel the discomfort of its subjects in the hope of us becoming better people ourselves.