Trauma, emotional or otherwise, is a much-plumbed source of horror in the genre. Nicholas Gyeney takes this time-honored wellspring of horror with The Activated Man and adds a new layer of discourse on a subject that is woefully underestimated in modern times: the death of a pet and the psychic and emotional damage it can do to us, a story about loss, confronting trauma, and the enduring power of the love we have for our pets.

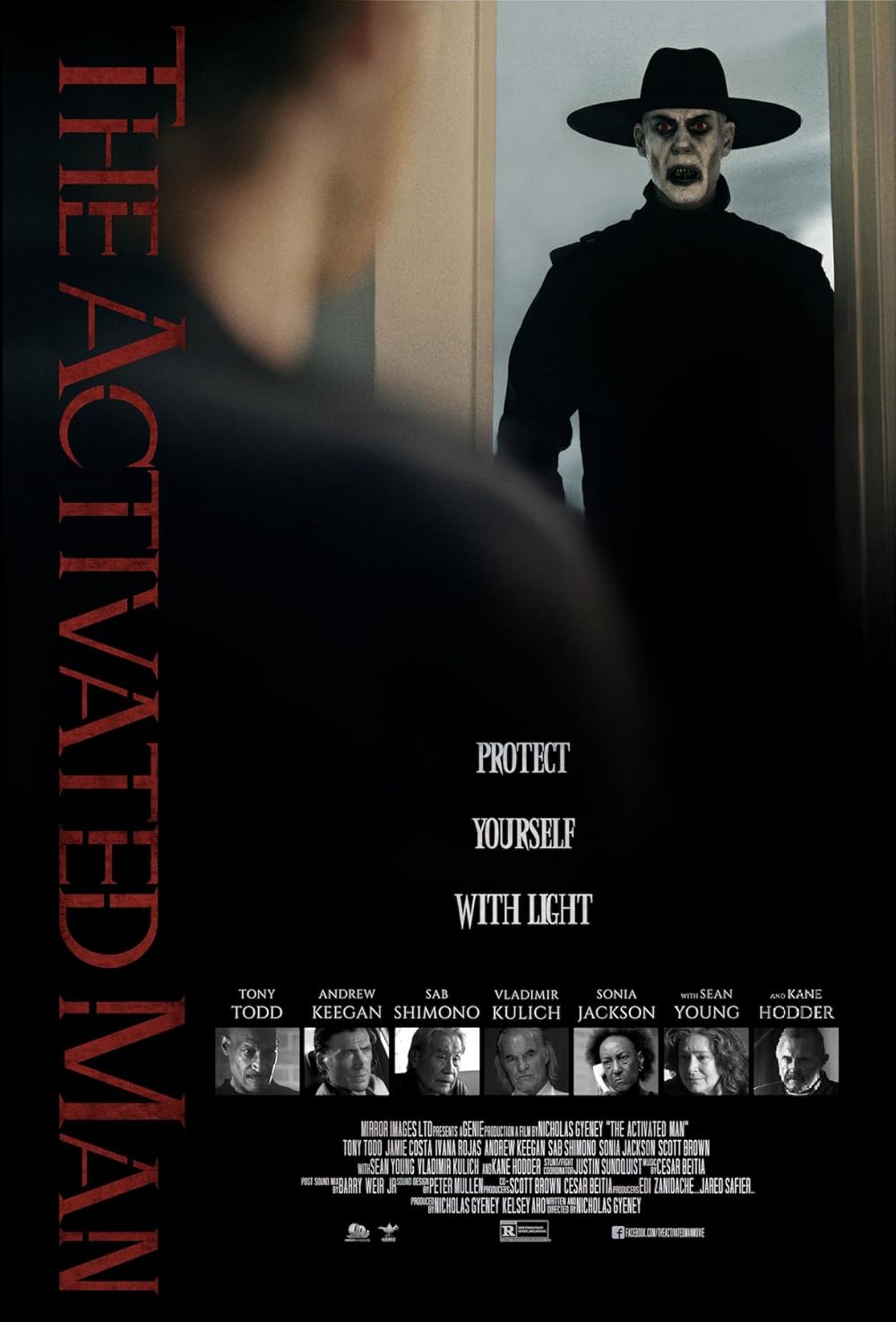

Ors Gabriel is not having a good time. His beloved dog Louie has recently passed and he’s starting to believe he might be losing his mind. Not only is he seeing visions of Louie around his apartment, but he’s also having visions of a nightmarish creature that may or may not be responsible for a chain of murder suicides across the country over the years: the Fedora Man. Ors must reach into his own past to figure out what’s real and what’s not before this nightmare consumes him one way or another.

All cards on the table: this movie might not be for everyone. It walks a very line between effectively dramatic and moving and being kind of cheesy. In the end I think it does succeed in being the former, but there are moments when it’s a touch saccharine. And that’s fine! Also, it hits very hard on the loss of a pet. The opening scene where Ors is reliving Louie’s death was tough for me to watch as someone who’s lost a pet (RIP Jacob Barker) and I’m sure I wouldn’t be the only one affected that way. It’s not cheap or rough for the sake of being rough, and it does serve a purpose in the story, but it’s still an aspect of the film that might be hard for some. So, heads up.

I think this film’s biggest strength is how it effectively weaves a common tragedy many of us have dealt with into its supernatural element. Ors heartache at losing his friend has left him open to the influence of something otherworldly and sinister, and I’m sure many of us who have suffered such loss certainly feel like there’s something hanging over us clouding our thoughts and making things worse for us. On the flip side, it also uses the idea of dealing with childhood emotional trauma as a kind of lesson on how to deal with loss; in Ors’ case, learning to process his relationship with his father helps him overcome the current horror he’s facing. It’s a simple but powerful metaphor on the subject that doesn’t feel too heavy handed.

The performances in this film also help sell the story of “the best way out is straight through”. Jamie Costa brings Ors to life as a man walking through a nightmare, giving him a constant veneer of ‘what the fuck is happening right now’ that fits the character perfectly. His relationship with the extraordinary, being the eerie visions he succumbs to or his struggling with the fact his beloved dead dog might not be as departed as he thinks, feels extremely relatable. The scenes where he’s sheepishly reaching out to Louie feels like we’re actually seeing someone truly reaching out in the hopes of reconnecting with a loved one. His transition from skeptic to believer is as steady as it is unsettling to watch, mostly because it comes at the cost of realizing, ‘oh my fucking god this shit is real?’ And of course, there’s Tony Todd, an absolute legend in the realm of genre filmmaking. His Jeffrey Bowman, a psychic and self-described light warrior, is a rock of stability in an increasingly insane reality for Ors. Todd is a modern-day Vincent Price, bringing a real gravitas to the role and a genuine warmth that is a foil to the chilling terror of the Fedora Man. Him talking to Ors about the powerful bond between us and our pets and how they help us get through life was like a weighted blanket wrapped around me; I got genuinely choked up seeing talk about the subject.

Ultimately, I think the film’s only real shortcoming is the choice in showing the face of the Fedora Man. An obvious analog to the Hat Man phenomenon, the Fedora Man is portrayed as something akin to Lon Chaney Jr. in London After Midnight; a pale faced, sunken eyed, pointy toothed ghoul leering out from the shadows. Unfortunately, the design doesn’t quite fit the uncanny nature of the “real” Hat Man, which is simply a silhouette that people describe as having the unsettling quality of seeming to stare at them as they lay paralyzed in bed. That concept is far more effective than what we see in this film, which unfortunately looks like it would be more at happen in Are You Afraid Of The Dark? or something similar. Had the filmmaker decided to go with a more minimalist look for the Fedora Man that could’ve added a more visceral quality to the film on top of the concept of loss and grief as horror.

The Activated Man is a story of loss and pain, sure, but it is in the end a tale of love and hope. Gyeney wisely reminds us that while that pain might never leave us entirely, nor will the good memories we carry of loved ones who have left us behind. It’s an effective examination of grief and fitting tribute to Gyeney’s own late pup, also named Louie, and it’s a reminder that no matter what happens after we die, be it oblivion or structured afterlife, we never truly leave those who live on in our wake.