I like to believe that I’m an even-tempered film fan, one who understands that not everyone watches movies with the same obsessive bent that I can (and often do) tend to bring to things. Sure, I’m all too happy to get riled up by petty disagreements in the ol’ discourse, but always all in fun. It has to be. If you can’t have fun with the stuff you love, then what fun is there in being in love?

But sometimes, you have to draw a line.

And there’s one snarky comment that comes up every so often, especially around this time, especially whenever people who have never seen it before decide to take a gander at John Carpenter’s seminal slasher forerunner, Halloween.

That comment is: “If Michael Myers was sent to an asylum when he was just a little kid, and if he’s just been sitting silently in a room for the intervening decades, how was he able to drive when he broke out?”

This shit comes up all the time, from fans and detractors alike. Alleged Halloween-superfan Bill Simmons brought it up as a nagging plot-hole during an appearance on the “Halloween Unmasked” podcast. It’s a ‘plot-hole’ that has been parodied and played up in humor videos and blogs. With regards to his excretable remake (a leading contender for the movie I hate most on this earth) Rob Zombie laughed off the idea of Michael Myers driving, saying that this element always annoyed him about Carpenter’s film.

Beyond not liking smug hacks taking cheap shots at one of my favorite movies, this line of mockery has always irritated the Christ out of me because it reveals how many people who see Halloween don’t actually watch the movie. Michael Myers being able to drive isn’t a plot-hole. It’s damn near the entire point of the movie.

First of all, let’s make something clear: if a movie specifically calls out and addresses a problematic or sticky plot point, then guess what? It’s not a fucking plot-hole anymore. By this easiest, most lax of standards, Michael Myers driving in Halloween doesn’t qualify as a plot-hole because in the movie characters bring up that he doesn’t know how to drive. As Donald Pleasance’s furious Dr. Loomis snarls, “He was doing very well last night!”

So it’s not a plot-hole. It’s not a goof, or a mistake. Fun fact: No matter how above the entertainment of the past you believe yourself to be, you are not smarter than John Carpenter and Debra Hill just because you’re able to jot down your every brainwave into a goddamn iPhone.

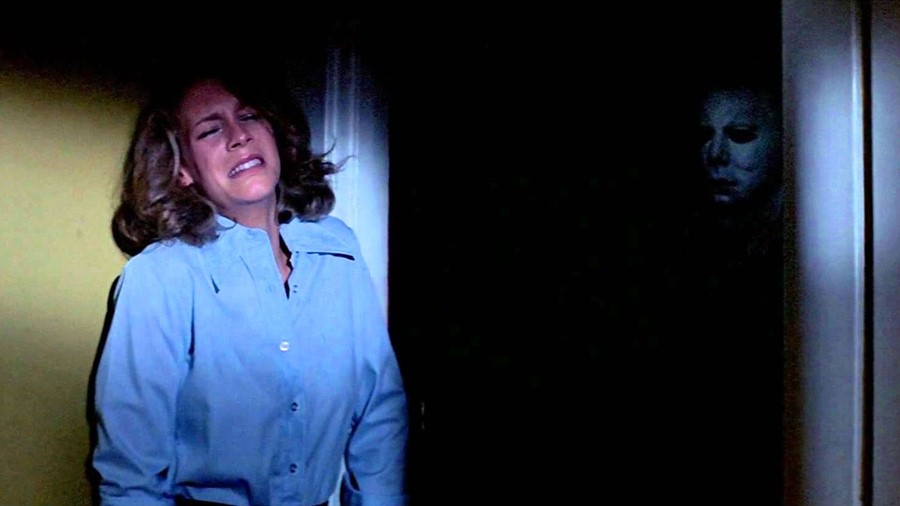

Anyway, this is neither here nor there. But it annoys me because if you only watch Halloween as a slasher movie about a creep who stabs half-naked (or less-than-half) girls, then you are missing out on those qualities that make Halloween an indelible masterpiece of fear. Sure, Carpenter delivers on the visceral horror of being stalked and slashed, creating a film filled with jumps and jolts even without a drop of blood in sight. But there’s another, secondary level of fear that Carpenter and co-writer/producer Debra Hill tapped into that is every bit as potent, and perhaps even more disturbing than the immediacy of “oh no, big man, bigger knife”. Through only intimation and cinematic gestures, through only tiny touches that are very easy to miss (as the continuous harping on about Michael driving proves), Carpenter and Hill conjure a feeling of almost otherworldly dread, and they elevate a masked murderer from creepy creep, to elemental Boogeyman.

Why does Michael Myers kill? Why does he target Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) and her friends? These are the questions that act like siren songs leading generations of filmmakers and other artists to crash onto the rocks of laughable explanations. Michael’s after Laurie because she’s actually his long-lost sister, no, actually Michael’s after anyone who might be related to him, no, see, it turns out that Michael has been cursed by a Druidic cult, no, forget all that, Jamie needed some extra cash so she’s back in so now Michael just wants to kill her because she’s his sister, got it. And these are some of the saner entries! The Halloween novelization published back in 1979 has a whole explanation where in ancient Celtic times a teenager murdered a girl who didn’t return his affections during the festival of Samhain, and so his soul was cursed to walk the earth forever and ended up possessing li’l Michael Myers and compelling him to kill.

The putrid Zombie remakes reduce Michael to the stock psychology of so many other serial killers, a sociopathic boy growing up in a broken home who kills small animals and then graduates upwards. Shit man, at least that Celtic nonsense was creative.

With David Gordon Green’s highly entertaining latest entry, which wipes away every single sequel, Green and his team seek to wipe the slate clean and leave Michael’s motives a pointed blank. Multiple characters in the film (mostly dudes) are obsessed with unlocking the secret behind Michael’s evil. Is it to do with Judith (played by Sandy Johnson in the original film), Michael’s older sister and first victim? Or is Michael’s bloodlust tied to Laurie Strode specifically? Green’s film posits that there are no answers, illustrated with a sequence in which Michael wanders from house to house on Halloween night, slaughtering anyone who happens to be home. There’s no rhyme, no reason, just an unquenchable bloodlust that has been sprung on the innocent by the curiosity of self-important men. Halloween ’18 of course builds to a showdown between Strode and Myers once again (marking the third time that Jamie Lee Curtis has conclusively killed the Shatner-mugged schmuck, only for sequels to spring him back) but it’s debatable whether Laurie ever once factors into Michael’s actions. He just seems to wander from kill to kill, and it’s pure chance (and the machinations of men who insist there must be a connection between these two) that brings predator and prey together and reverses their roles.

But while Green’s film positing that there is no reason for Michael’s actions feels closest aligned to what Carpenter cooked up, it still doesn’t get it just right. Because, see, there is a design to what Michael does in that first movie. In Green’s film, if Michael Myers sees you, you die, but in Carpenter’s original, he lingers and lurks, haunting Laurie and friends but never pushing his advantage. Again and again Carpenter constructs scenes of great vulnerability for Laurie and the girls, and again and again Michael Myers lets these opportunities pass him by until he decides to strike.

Why those moments? Why does he kill Annie (Nancy Loomis) in the car but not when she’s stuck in the laundry window? Why does he study Bob’s corpse the way he does? And why does he pose Annie’s corpse on the bed beneath the stolen gravestone belonging to Judith, while Bob (John Michael Graham) and Linda (PJ Soles) have their bodies crammed into closets and crawlspaces, a tableau that seems to exist purely for the benefit of Laurie Strode when she finally stumbles into this house of horror?

How did he know that Laurie Strode would come?

I used to think the scariest thing about John Carpenter’s Halloween was the idea that Laurie Strode’s only misstep, the thing that put her in the path of the Boogeyman, was that she happened to walk up the steps of the Myers’ house while Michael was inside. It could have been anybody who ran up the steps of the “spook house”, but dumb chance meant that it was Laurie who took those fateful steps, unaware that Michael was just on the other side of the door.

But now there’s another, more horrifying, idea that strikes me whenever I see that scene: It’s not chance. Michael doesn’t follow Laurie because she happens to come to the door while he’s standing there. He was standing there waiting for her.

The scene immediately following Laurie stopping by the Myers’ house is the one featuring Dr. Loomis hollering “He was doing very well last night!” followed immediately by the famous one in which she sits bored in class and happens to spy Michael spying at her from the curb. The teacher droning on in the background may as well be regaling the class with a recital of Charlie Brown style “womp womp womp”, but what she’s saying is a wee bit more interesting than that.

“You see, fate caught up with several lives here. No matter what course of action Rollins took, he was destined to his own fate, his own day of reckoning with himself. The idea is that destiny is a very real, concrete thing that every person has to deal with.”

A question posed by the teacher pulls Laurie away from the far more important work of Michael-watching, but she responds off the cuff with, “Samuels felt that fate was like a natural element, like earth, air, fire and water.”

Carpenter, then, is staking the eventual battle between Laurie and The Shape along cosmological grounds as well the standard “Knife! Bad!” concerns. For reasons Laurie can never know (but that Michael might?) they are bound together. Evil, Halloween suggests, is not random. There might be comfort yet in chaos. Evil selects you and hunts and hurts you, and all a person can do is “deal with” it.

The school scene in Halloween put me in mind of another calm-before-the-storm bit in an acclaimed proto-slasher. In Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, before any actual chainsaws or massacres appear, one of the doomed kids in the doomed van reads their horoscopes, all of which suggest that bad things, some so horrible they can scarcely be believed, are imminent for the kids.

Like the classroom scene, this dialogue could be chalked up to little more than time-spinning chatter, but Hooper would later point to this scene as the fulcrum around which all the horror of Chainsaw moved.

“It’s about a bad day,” Hooper is quoted as saying. “It’s about a cosmically bad day.”

Here again, we have a film that assails you on both physical and spiritual levels, that suggests that the petty horrors of human violence are staging grounds for deeper, darker conflicts that transcend our abilities to understand reality.

But really what joins these films together in my mind, and what elevates Halloween (and Texas Chainsaw) to the status of masterpiece is that these cosmic forces of darkness are unleashed on good kids. In virtually every slasher to be spawned in the wake of Halloween, the victims of the month have some kind of comeuppance coming to them. They pulled a horrible prank, they went somewhere they were told not to, they killed someone(?), their parents committed some kind of terrible crime that has been passed down to be paid for, they drink and fuck and act like assholes, etc. etc. This tendency got especially played up once killers like Jason and Freddy asserted themselves as the protagonists of their respective series, but even in the earlier movies which should theoretically have had something like a functional moral compass, there’s an Old Testament sense of morality to who gets got.

In Halloween (and Texas Chainsaw [and Black Christmas]), bad shit just happens. These movies were produced directly in the aftermath of Vietnam, the collapse of the hippie movement, the assassinations of JFK, RFK, MLK, the list goes on. In their own way, these slashers predict Hunter Thompson’s famous “The Wave” speech, depicting a moment in which it becomes clear that everything is not necessarily going to be OK, that having great moral clarity and a sense of purpose will not always be enough to stave off what the universe is going to throw at you.

There’s no reason for Laurie Strode to be targeted by Michael Myers. There’s nothing she’s done or could do to merit being the one he zeroes in on. But some force greater than herself, greater than any human, compels The Shape onward, spreading misery and death wherever it goes. All Laurie can do, all anyone can do, is try to weather the storm until it passes overhead. And when it does, there’s no triumph, no celebration. Only the memory of evil, and its scars, a nightmare that announces itself in every former safe space now perverted and hostile.

I don’t care if you find 1970s outfits cheesy, that’s fucking scary, that is.

1 Comment

Matt D Snyder

Well said. Anyone that has gripes about the why’s in films, doesn’t know how to escape from reality and enjoy 90 minutes of fantasy.