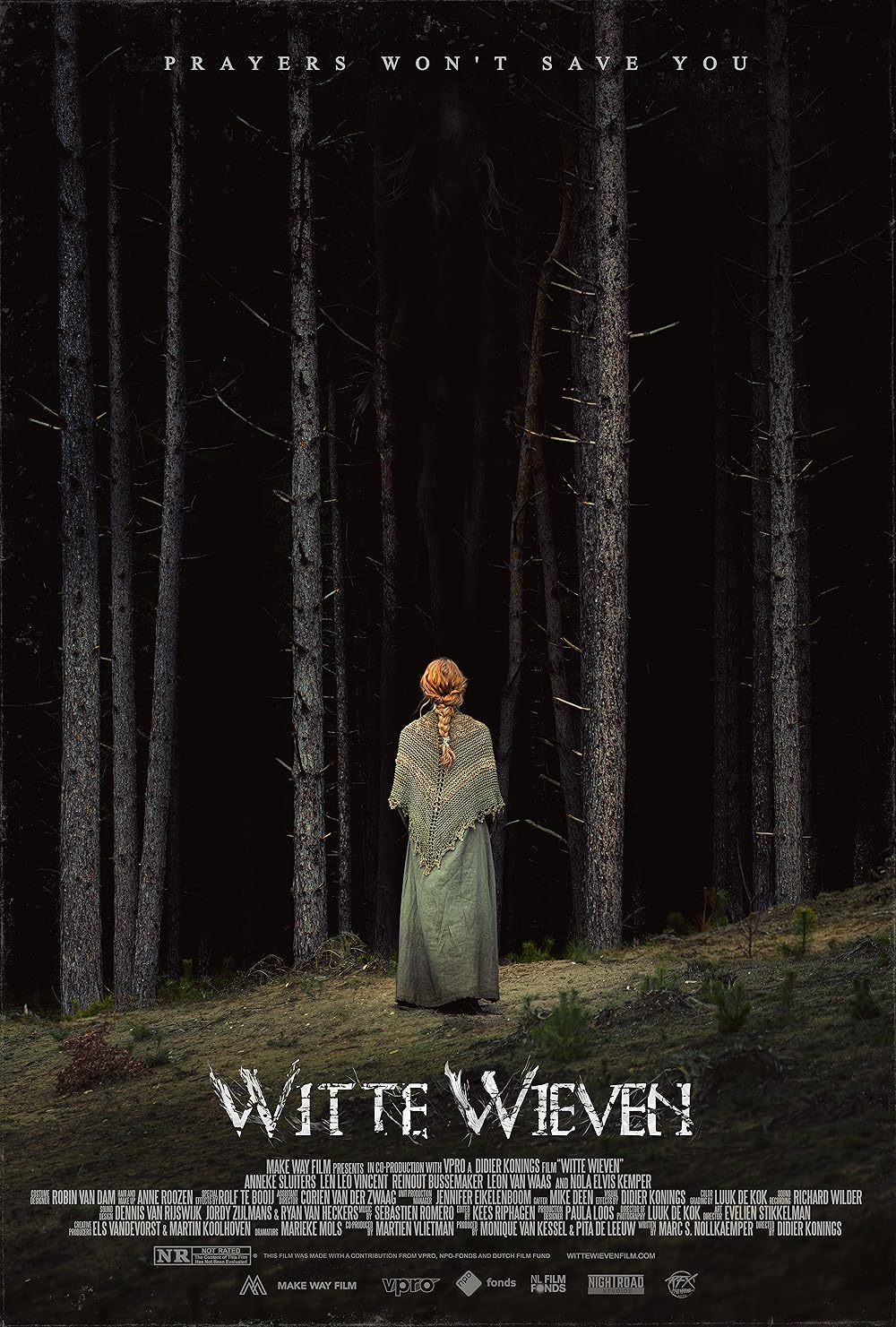

Religious horror and folk horror, much like flies and vampires, go together like bullets and guns. The two concepts intertwine so often and easily that it feels like they usually work best together. Similarly, the concept of “the oppressed feminine” fits so perfectly with the two that it feels tailor made. Didier Konings Heresy (Witte Wieven) masterfully blends these ideas into a haunting tale of religious guilt, oppressive patriarchy, and spooky forest creatures.

Frieda and her husband have a problem. Well…Frieda has a problem, as her husband has violently insisted that their inability to have a child must be her fault. She’s tried every trick in the book, Christian and pagan, but it feels like maybe it’s just not in the cards for her to have children. One day, while out in a forest that is supposedly cursed, Frieda is assaulted by a town deviant, and despite escaping his insidious intentions she finds herself in the midst of a spiritual crisis. The town has decided she herself is now cursed and must be dealt with. She soon finds herself wrapped up in a nightmare of misogyny and zealotry.

Anneke Sluiters as Frieda shoulders the narrative weight of this film and successfully carries it across the finish line, crafting a protagonist that draws in the audience immediately at the onset. Frieda is loveable and meek, and you can’t help but root for her to weather the storm of bullshit her village is putting her through. Her defiance, quiet at first but increasingly violent, in the face of institutionalized misogyny is awesome to watch unfold to its gloriously blood-soaked end.

The film makes a bold choice of making it quite clear that the inhabitants of the cursed forest are indeed real while make it equally clear that Frieda’s fellow villagers are the true villains of the story; indeed, the men in this film are far more frightening than any of the creatures Frieda encounters. It’s a rather unsubtle commentary upon not just the traditions of mediaeval Christianity but also of modern-day society in which women are not just reduced to breeding stock but also as sexual objects. Similarly, Frieda’s husband’s insistence that it has to be Frieda’s (re: the woman) fault that they can’t have a child is a tragically common concept that also ties a woman’s worth to their ability to procreate.

It’ is a testament to Konings skill as a filmmaker that they are able to craft a movie that features supernatural aspects on the outskirts and doesn’t have them feel unnecessary. Indeed, the fantastic beats of the film feel just as essential as any other random element of the film. It makes the film feel even more like a story of rising above oppression and becoming more than the world wants you to be.

Heresy is not a traditionally scary film, but it is absolutely unsettling. The casual objectifying of Frieda is more than enough to unnerve and get under your skin, and at just over an hour this film has zero fat to trim away. It’s a sleek and streamlined look at archaic and superstitious bullshit has mutated over time to still fester in modern society, but it’s also a film with a message that no matter how bad things get, there’s still hope to utterly smash your oppressors and embrace your inner feral forest creature.