Necessity is often the mother of invention, and in last days of the Roaring 20s, a lot of performers found themselves in need. A decade’s worth of economic exuberance was headed for one hell of a hangover. The once massively popular vaudeville circuit was rapidly losing ground to the comparatively new technology of sound films and commercial radio, the theater footlights being rapidly swapped for movie screens. If vaudevillians were going to survive, they were going to have to adapt. Naturally, it was a stage magician that managed to conjure something up that felt entirely new.

Elwin-Charles Peck (better known by his stage name El-Wyn) was a career illusionist, a “mentalist” who could fool packed houses into believing he had genuine psychic ability. Spiritualism was still sweeping the nation, even if famous skeptics like Harry Houdini had proven these mediums and their seances were little more than a disingenuous use of the classic techniques and props of stage magic. El-Wyn reframed old tricks in the language of a new fad.

Announcing a midnight show at whatever theater he was booked in for the evening, his patter and his tricks would all center around a ghostly theme. Tables would be rapped by unseen forces, objects would move on their own, strange sounds would fill the hall. The show would culminate in a dramatic blackout where luminous “ghosts” of cheesecloth and phosphorescent paint would appear throughout the venue.

“El-Wyn’s Midnight Spook Party” became an immediate, widely imitated success. Previously out of work performers could easily rebrand as a “ghostmaster” and adapt their skillset to suit the format. Theater owners gained a new source of revenue, making money during time periods the theater was usually dark. Audiences loved the late night adrenaline rush of a good scare, and happily lined up around the block.

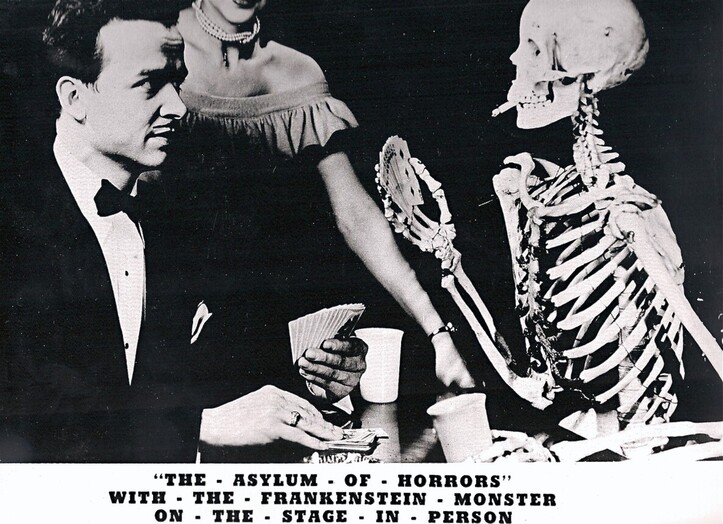

As the 30s gave way to the 40s, the circuit of “spookers”, “ghost shows” and “spook shows” moved from supernatural specters to outright monsters, thanks to Universal Studios’ run of horror hits and a performer named Jack Baker, popularly known as Dr. Silkini. “Dr. Silkini’s Asylum Of The Insane” tweaked El-Wyn’s basic formula into a ready made midnight double bill, combining the stage show with the screening of a bargain basement horror film. Sitting between the ballyhoo of the sideshow and the “hot and cold showers” approach that made Paris’ Grand Guignol a success, Silkini upped the gore and the goofiness into zippily paced horror-comedy. The bloody illusions would be intercut with lighthearted bits of audience participation and crowd volunteer hypnotism. Promotional gimmicks like temporary graveyards outside the theater or a giveaway for a souvenir dead body (read: a frozen chicken) became standard operating procedure.

There might be some classic glow in the dark ghosts incorporated into the show, but the live shows became dominated by more gruesome and complex effects. Rather than a seance ghostmaster, hosts began rebranding as mad scientists and creepy doctors. This switch came complete with a faux lab or dungeon visual theme and dramatic illusions of dismemberments, decapitations, and reanimated corpses.

Assistants would pose as the closest copies of the Universal Monsters as copyright law would allow, and the blackout finale often hinged on these cinematic terrors getting loose in the theater just as the venue went dark. The audience, already primed to be scared by a lengthy catalog of the terrors to come at the start of the show, would erupt into pandemonium. This updated format of the “midnight monster show” was so incredibly popular (and insanely lucrative), that even Bela Lugosi himself had a brief stint as a host during the late 1940s.

New technologies and shifting tastes in entertainment had allowed spook shows to flourish, and those factors caused their inevitable decline. Television became more readily available during the 50s, and the theaters were removing their stages to better accommodate projection of new cinematic formats. The rise of the splatter film in the early 60s, and the ascendence of drive-ins took the limping art of the midnight monster show and firmly drove the final nails into its coffin.

The B movies usually shown on the double bills were readily available elsewhere, and the sort of darkness dependent illusions the live act hinged on were borderline impossible in the open air of a drive in. In the face of cinema’s new taste for a more luridly bloody horror, spook show style shocks became more tame than transgressive.

Mid century television shows like Chiller Theatre, Shock Theatre and Dig Me Later, Vampira were small screen recreations of the macabre humor and retro chillers that had been such a success for the legions of spookers, introducing a whole new generation to their darkly comic camp. Popular ghostmaster Philip Morris (professionally known as Dr. Evil) even received his own program. Dr. Evil’s Horror Theatre ran for East Coast based network affiliates well into the latter half of the 1960s.

While the comedy side of the spook shows found a new home on television, the theatrical terrors and practical effects that characterized the live acts found a new home in rock and roll. Alice Cooper’s entrance in an electric chair, singing his way through a set while carrying his own (seemingly) severed head. GWAR’s elaborate metal mythology and their embrace of on stage assassinations and an ample spray of faux body fluids into the crowd. KISS levitating instruments across the stage in a fugue of greasepaint and dry ice fog. With bigger budgets and better prop blood, shock rock built itself a home on a foundation the former vaudevillians of the spook show had built.

Though Spiritualism never again reached the popularity it enjoyed in El-Wyn’s day, the mysticism it brought to the spook show stage continued to influence rockers well into the 80s. Glenn Danzig’s work with both Danzig and the Misfits mixed occultism with pure atomic age morbid youth culture doo-wop drama. His entire catalog is a foul mouthed soundtrack for the Famous Monsters set who had grown up on a steady diet of Chiller Theatre. As for Zombie, he named his band after the 1932 Bela Lugosi film, his entire hellbilly aesthetic built on the dark ride visuals, carny hustle and classical genre cinema that fueled the later period midnight monster shows. Both men are clearly fascinated by the ghastly grin of the darker tinged popular entertainments that dominated an older, weirder America.

The live midnight spook shows were all but memory by the early 70s. However, like the protagonist of any good scary story, the spirit of the spook show never really died. It crawled out of the grave of cultural relic to sink its spectral talons into the imagination of several generations. While “fandom” as a concept had yet to fully enter the popular imagination, spook shows were one of the first big touchstones for an (at the time) unnamed subculture of horror hounds.

There was something special lurking there in the dark as the house lights cut to black. It might make you laugh, scream or maybe even cry. The only way to find out was to wait for the stroke of midnight and take your seat. A ghost might sit beside you, or a snake might slither across your shoes. For the newly minted monster kids that came out of the other side of the double bill forever changed, it was magic.