Someone far wiser than me once said, “mental illness isn’t your fault; but it is your responsibility.” In other words, you can’t be blamed for the cards you were dealt but it’s up to you to work with whatever hand you have. Melora Donughue and Kimberly Stuchwisch’s Canvas is a blunt, no frills, on the rocks look at how a disregard for mental health, intentional or otherwise, can manifest itself in not just straight up abuse and all sorts of violence but can also go on to warp the lives of others down the line.

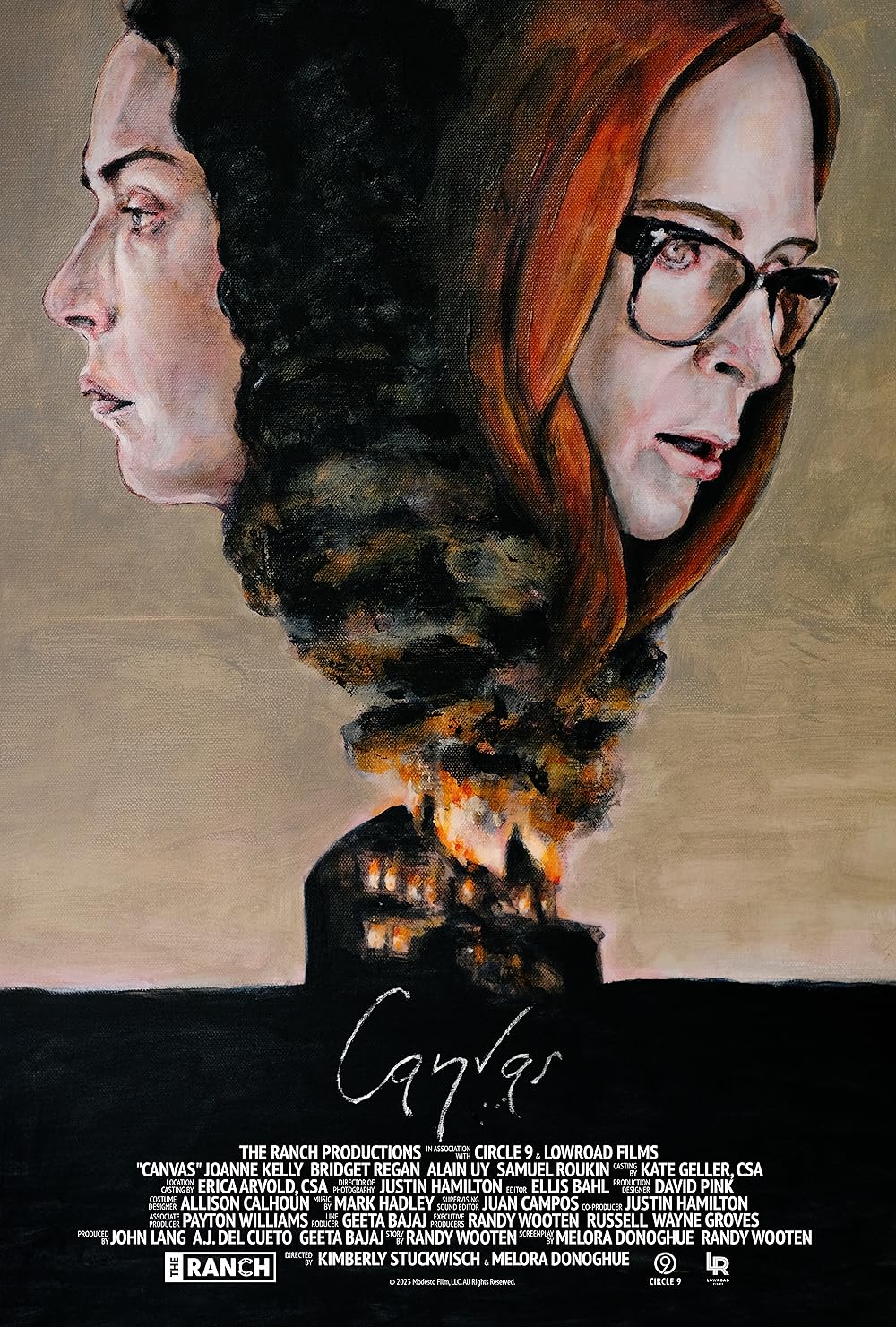

Canvas is the story of Marissa and Eve Hale, a pair of sisters who were the daughters of a tremendously talented but also violently ill artist. Forced into competition at a young age by their father’s incessant drive to see them succeed as artists themselves, Marissa and Eve are still reconciling with their father’s illness as adults: Marissa, the elder sister, seems to have inherited her father’s obsession with succession and callousness in achieving it. Eve, on the other hand, was gifted with her father’s talent and mental instability; she paints profusely but refuses to have her work shown and has instead become a recluse in her childhood home. Canvas shows us how these characters have gotten here and the train wreck that results when their lives collide once again.

Donughue and Stuckwistch craft a remarkably streamlined film, utilized a hefty number of flashbacks to flesh out the tragedy of the Hale sisters. Some might find this uneven and distracting, as the film tends to go back and forth quite often, but it’s essential in really driving home how truly fucked these people are. Bridget Regan brings to life a Marissa Hale who is perfectly monstrous, a being laser focused on success. She is callous, cold, and glass like, with any emotion other than annoyance or anger coming as a near perfect mask. Where Regan truly shines is highlighting a sadly essential characteristic of Marissa: her love of creating art far, far exceeds her actual talent for doing so, and thus is borne quasi-Tantalean story of constant striving and constant failure. Marissa’s only real love is the one thing that eludes her, and Regan ultimately reveals her as more pathetic than anything else. Joanne Kelly, on the other hand as the prodigal younger daughter Eve, excels at showing what happens to someone not as…adapted as Marissa. As the sole witness to the horrifying tragedy that sparks the story, Eve has become a shut in, a hermit in her childhood home, speaking only with her father’s long-time agent. She is effortlessly what Marissa maddeningly wishes, creating at a whim breathtakingly gorgeous works of art. She has no regard for glory, or recognition, or money; she simply creates for the sake of doing so. Unfortunately, Eve has fallen prey to what seems to be a horrifying case of anxiety and panic disorder. She is not frail, she is not cracking under the weight of anything: when we meet Eve as an adult, she is utterly smashed to pieces by what she has witnessed and is content with simply living in the wreckage of it all. Kelly’s Eve is achingly vulnerable, almost childlike. Not so much “deer in the headlights” as “horse smelling smoke”, Eve is wary of the intentions of everyone, rightfully seeing right through her sister’s bullshit when Marissa approaches her at the beginning of the story. Marissa might play the cool and aloof puppet master, but Eve is ultimately the more competent one of the two.

Canvas might not be for everybody; it’s intent on telling a story rooted deeply in the past and for some that might come off as disjointed and uneven. At times, it’s hard to tell if the flashbacks are the true story with the present sections of the film serving as epilogues. In the end though it succeeds in telling that story, one of tragedy and obsession and trauma. It’s a restrained film for the most part, sometimes slow to the point of feeling meandering, but the few deeply emotional beats are devastating. In the end, it succeeds in telling the story it sets out to, a bleak but rewarding tale of struggle and perseverance in the face of mental anguish.