WARNING: SPOILERS

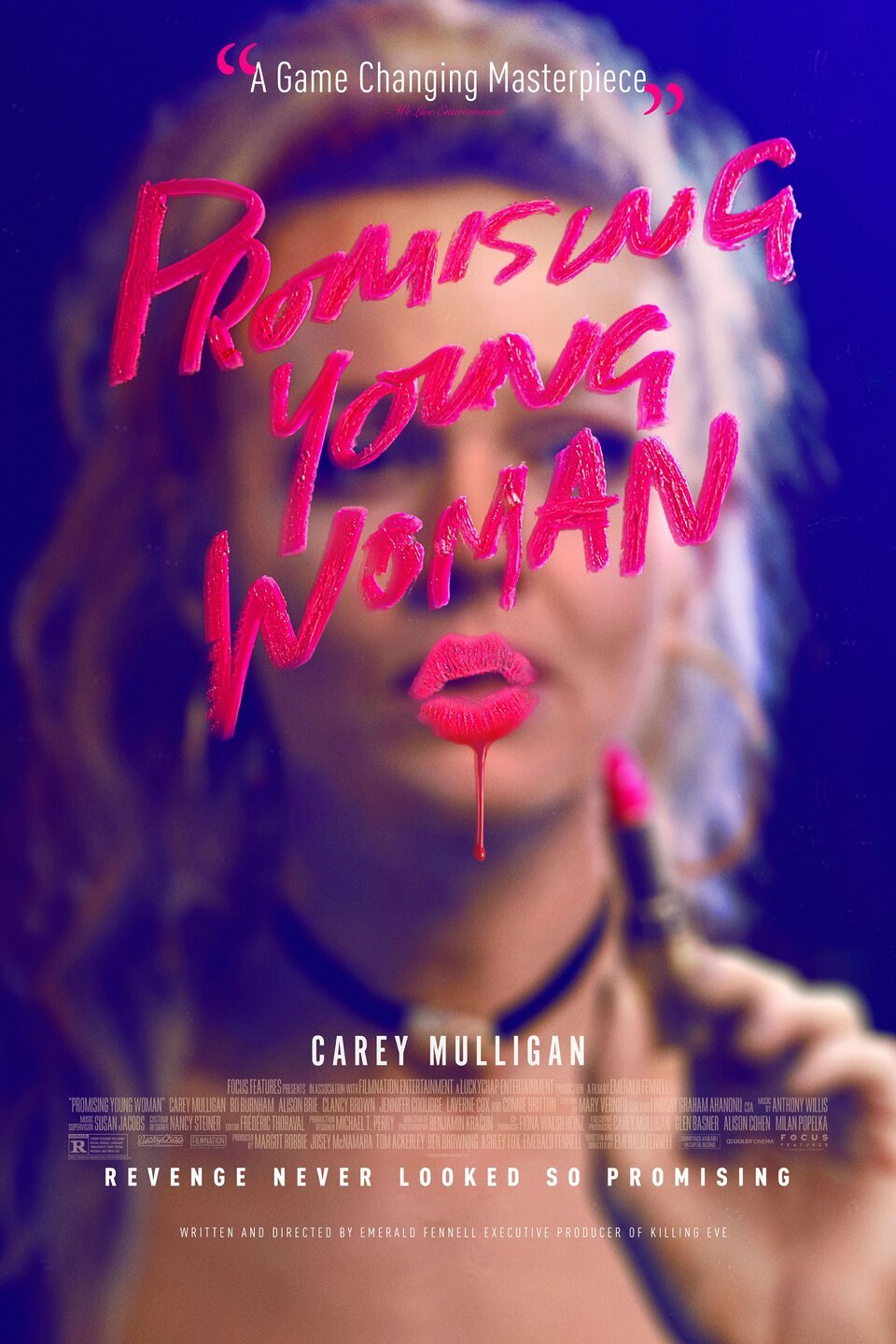

Promising Young Woman, directed by Emerald Fennell of popular series Killing Eve fame, is the story of Cassandra Thomas and the slow burn revenge plot to avenge the sexual assault of her friend Nina, who commited suicide as a result of an assault in med school. Nina’s justice was non-existent. After Cassandra’s efforts led to multiple dead ends, Nina’s rapist was left with his future intact. Cassandra painstakingly goes after those who were culpable, but seems to abandon her quest when she reconnects with Ryan, (Bo Burnham) an old med school student, who comes off as a genuinely caring and considerate person. She works in a coffee shop at a job for which she is clearly overqualified (she dropped out of med school) but is at least accompanied by Gail, (Laverne Cox) who is a source of support. Cassandra’s relationship with her parents is also rocky but her father is the only other person who supports her—even with her actions as a result of trauma. The arguments against victim blaming and sexual assault bring foward important points of toxic rhetoric perpetuated when victims of sexual assault come foward. Sayings that blame victims by saying they are “asking for it” or are lying about the severity of the assault itself (which is brought up with Alison Brie’s character Madison). Although the film’s points regarding rape culture aren’t wrong, there are some glaring issues with the film’s message towards sexual assault survivors and its wishful thinking towards the US judicial system.

The film is set up to defy the often exploitative, rape revenge narrative by giving the plot several twists; yet the twists ultimately do not work for the film’s story. Cassandra Thomas’ (Carey Mulligan) character arc goes no where, she is given no catharsis like typical rape revenge films, like [the original] I Spit On Your Grave, where the survivor prevails through swift justice. Although, at times it can be exploitative with grueling rape scenes that aren’t worth the torment when the perpetrators are eventually killed. While the reality of trauma is real and can even become debilitating, Cassandra’s whole identity is consumed by survivor’s guilt from the brutal rape of her best friend Nina. The trauma of losing her friend who ultimately committed suicide weighs heavy on her soul; she dropped out of med school and lives with her parents while working at a local coffee shop. This is something that is painted in a highly negative light to show that her character is so consumed by her pursuit for revenge that she has abandoned seeking her own happiness. Cassandra’s response from a traumatic experience is understandable in many ways, her friend is gone while those who committed sexual violence have gotten away with it. I have no major problems with her character’s history because it gives her a motive for her cold doses of revenge throughout the film. Three of the film’s strongest points were its only points that held water in terms of it’s arguments against institutional patriarchy, accountability and showcasing that women can be just as complicit in sexual violence. Madison (Alison Brie), Cassandra’s former med school friend is reminded in the harshest way by drowning Madison in anxiety as she battles the possibility that she could have been raped. Madison’s state of panic reveals the ugly reality survivors feel after a foggy night with only small portions to fill in overwhelming gaps in memory of the night before. Some are doomed to always question a night in which answers will never be answered no matter how many times it is revisited, all that is left is an impression of someone who may have taken advantage. Cassandra’s pity was only extended to Madison after she provided her with crucial evidence regarding Nina’s assault which is manifested when Cassandra ends her psychological torment. The revenge sub-plot of Madison was particularly harsh because Cassandra is subjugating her to what she perceives as sexual assault and is taught that unfortunately, it can happen to anyone in an instant. It is what women, non-binary, and trans folks often fear the most; the act itself, the trauma, no sense of justice, and the rough road to recovery.

In the film’s climax, Cassandra infiltrates Al’s bachelor party posing as a sexy nurse stripper, who apparently is unrecognizable to former college buddies. Nevertheless, she is able to handcuff Al and slowly reminds him of his heinous actions against Nina while preparing to engrave Nina’s initials on him. While he begins to panic as he realizes that she is Cassandra, Al bursts into tears attempting to justify his actions by citing that being accused of rape is a man’s worst nightmare. The shot then shifts to Cassandra, who sits atop of him, centered within a balanced frame and a slight glow behind her as she calmly asks, “what do you think a woman’s worst fear is?” A frighteningly real sentiment that forces a mirror back at the viewer, forcing us to consider either our own trauma or face the reality that our society is still very much riddled with sexual violence. Even in the post #MeToo era, it is an uphill battle to get convictions on sexual violence, which is at the crux of Cassandra’s arc who has not seen any justice for Nina. While Promising Young Woman may present itself as an unapologetically feminist film that is founded on empowerment and seeking justice through revenge, the message deflates by the end.

Al’s arrest is meant to be seen as cathartic because Cassandra has reunited with Nina (by sacrificing herself) and because of Al’s subsequent arrest for her murder. This assumption illustrates a critique of the criminal justice system’s nearly non-existent prosecution of sexual assault cases. It is a valid critique of the reality that hardly any cases get prosecuted, which is why it was so historic when Harvey Weinstein was finally arrested and eventually charged for sexual assault. This is largely from a feminist standpoint, that the justice system must be reformed in order to shake it’s patriarchal foundation and convict those who commit sexual violence. It is a twist that subverts the swift justice usually afforded to protagonists in rape revenge films, like I Spit On Your Grave which are afforded some form of justice. Yet, Promising Young Woman attempts to subvert swift justice by emphasizing the arrest as justice that is served while Cassandra sacrifices her body to avenge another. Cassandra’s fate is similar to Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise, whose protagonists get revenge but ultimately pay with their lives. Cassandra’s story is given an abrupt end that robs her character of any arc and leaves her as someone who is nihilistic and static. The Kill Bill-like momentum ends abruptly and leaves a person who has become totally consumed by what happened to her best friend that she does not heal and dies as a sacrificial lamb. I felt as if the film was telling the viewer that there is no path towards healing from a traumatic event like sexual assault, that it will completely and utterly dominate your life.

As I stated previously, the effects of trauma can be severe but for those who have access to the right tools and a support system, healing can become a possibility. This is of course a luxury to most and not in any means accessible to those affected hardest from lack of resources for survivors. To tie into Cassandra’s character arc, her character remains static with a weak catharsis that delivers a negative message to any survivor who is struggling with trauma. What kind of message does it send when a woman is portrayed as a strong femme fatale who seeks justice, only to sacrifice her body by getting killed by a rapist and calling it a day when he is arrested. By the end of the film Cassandra highlights what is missing within the US in general- feminism outside of carceral feminism. Promising Young Woman is a lukewarm play on a rape revenge story that does not provide any new insight in the ongoing feminist discussion in the US. Additionally, further criminalization will ultimately disproportionately affect Black and Brown folks under the guise of the pursuit of justice. There is a need for imaginative films of a what a feminist future will look like, what feminist justice will look like, what suppport for survivors look like, and what healing looks like, not just a grim snapshot of discouragement.

While my fellow mujeres and I ripped Promising Young Woman to shreds via zoom, another friend jumped into the conversation with an interesting point in which he compares the film’s bleakness to that of Park Chan-wook’s 2003 film, Oldboy. To which I can agree with on some level considering films like Lady Vengeance (2005, part of the Vengeance Trilogy) and Kim Jee-woon’s 2011 film, I Saw the Devil where the protagonists are completely consumed by trauma but have elaborate plans for vengeance. Cassandra’s character fits within the framework, she is consumed by her trauma (from losing Nina and no justice) and her elaborate plan for revenge unfolds from the moment the film begins. Much like the Korean films mentioned, the endings aren’t happy ones in comparison to the ones commonplace in American films. Although I can agree with reading this film considering possible influences, I don’t think it works within the context of the US given #MeToo and the Women’s March. (Both have been criticized excluding women of color). But because the US frames justice within the confines of the carceral system, there is an over reliance on an unjust carceral system to face massive reform in order eradicate the problem.

Within the context of the US, Promising Young Woman comes off as a rape revenge fantasy from a carceral feminist lens that ignores institutional racism entrenched in the criminal justice system. As much as the intentions of the film are understandable, which is pushing for justice via the judicial system, it also unfortunately inevitably includes more reliance on a growing militarized police force. Black Lives Matter’s call for defunding police wasn’t just about scaling back funding for police or solely about abolition. It was also a call to redirect money from bloated police budgets into resources for working class communities of color.

Why push the call for more reliance on a judicial system that already has a terrible track record with gendered violence, not to mention unwillingness to recognize femicides as a problem within the US. Similar to the Banana Republic comparisons after January 6th, American exceptionalism associates femicide with the “other”. If feminism has any chance of sparking a mass movement ignition, it must incorporate how to provide resources for survivors and uproot the foundation of patriarchy in society (rape culture, victim blaming, gaslighting etc).

Although Promising Young Woman does address a harsh reality of sexual assault, it asserts to the viewer that you will ultimately have to sacrifice your body in pursuit of justice and by justice it means to arrest your perpetrator and die at the hands of a rapist for posthomous catharsis. The film asserts that the path to healing is non-existent, which is a pretty dangerous message to send to survivors. It is the same tragic ending afforded to Thelma & Louise that begs the question, why must hurt women continuously suffer? A rape revenge twist that is just another cliche that sends a mixed message to survivors does not make it a feminist film. Just because it exists does not make it revolutionary! These discussions about feminist films are not happening among popular critics, who are to say the least, majority white or white men. Since there are limited voices among critics, there is a lack of important discussions coming from critics of color. Films themselves are a window into popular culture and a snapshot of how American audiences perceive or create media from what passes as a feminist films. Critics are a reflection of that and if the conversations are relegated to those most privileged then there is no informative and much needed analysis coming from Black, Indigenous and/or people of color critics.

According to Rotten Tomatoes, Promising Young Woman has a 91% approval rating among critics and 88% audience score, which illustrates its success across the board. In the midst of my zoom discussion with fellow cinephiles, we acknowledged the importance of film critics of color and the lack thereof; especially within the context that the film has been widely praised. The status quo reaffirms Cassandra’s character arc as as if she has a complete one, in favor of an incoherent and odd message for rape survivors. Feminist films should not continusosly focus on white characters while Black and Brown characters remain in the background, especially in 2021. Representation isn’t only about seeing yourself on screen but having characters that have complete arcs who are integral to the narrative. Lastly, representation is also necessary among critics who are given platforms to contribute to critiquing films; no films are immune to critique including the films marketed as seemingly unapologetic feminist ones like Promising Young Woman.