For most comic book fans, there’s little question that the traditions and conventions that came to define Western superhero comics are rooted in the Golden Age: a period that began with the first appearance of Superman in Action Comics #1 in 1938, lasting roughly through the early 1950s. During this time, comic books emerged as a developing industry, bolstered and popularized by heroic characters that tapped into the fears, anxieties, hopes, and dreams of a culture.

With America still pulling out of the Great Depression and the threat of war looming ever nearer, it’s no wonder comics gained popularity. Readers could connect with characters like Superman and Captain America, two of the foremost characters of the Golden Age; they were champions of the oppressed and the downtrodden, beacons of light in dark and troubled times. Their stories depicted altruistic heroism and the promise of good conquering evil, and they took on crooks, corrupt politicians and organized crime; very real societal problems. Comic books were a much-needed morale-booster for the times.

Within the greater context of the evolution of comics as a medium, The Golden Age was a time of experimentation. The Comics industry was in its infancy, its potential still being tested. Creators were experimenting with content, form, and style to varying degrees of success. At the same time, realizing that this might be more than a fleeting fad, many pulp publishers turned to publishing comics, engendering a genre explosion. Caped crusaders, science fiction, jungle adventures, romance, westerns and more emerged. Some of the work to materialize during the Golden Age is among the wildest and weirdest of the medium. Very little, however, was as singularly bizarre as what emerged from the mind-boggling imagination of Fletcher Hanks.

Hanks was born in Patterson, New Jersey, on December 1, 1889. As a child, he showed an interest in drawing, but it wasn’t until his early ’20s that he enrolled in courses with the W. L. Evans cartooning correspondence school. Through assignments, Hanks developed a traditional cross-hatch style common to artists of that era. Eventually, Hanks took a job working for Will Eisner, before moving on to lesser-known publishers Fox Feature Syndicate (original home of the Blue Beetle) and Fiction House, for whom he created the majority of his of output. His work appeared in anthologies, as was the standard for the Golden Age, books such as Jungle Comics, Fantastic Comics and Fight Comics.

Hanks was an auteur, handling the line art, coloring and lettering himself, producing roughly 50 stories from 1939 to 1941 before withdrawing from the industry completely. His motivations for doing so are unknown and details of Hanks’ personal life in general are scarce. An interview with his son, Fletcher Jr., published in cartoonist Paul Karasik’s I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets, was for a long time the only major source of biographical information available about Hanks. The picture painted is bleak: Fletcher Hanks Sr. was a violent and abusive alcoholic who abandoned his family in 1931, taking his son’s piggy bank money with him.

He froze to death on a Manhattan park bench in 1976.

Hanks remained an obscure, forgotten figure for decades, until Karasik stumbled upon his work and brought it to a wider audience. It wasn’t long before Hanks began to gain a cult following, and if you read his comics, you’ll understand why.

What initially draws readers in is the surreal quality of his artwork. Entirely abandoning the disciplined cross-hatch style of his earlier days, Hanks forged a distinct, signature style defined by warped and exaggerated linework, eschewing any semblance of anatomical accuracy. His figures appear misshapen, with alien proportions, and they populate a world of garish colors and grim fates (more on that later). Curiously, as grotesque as they often are, the crudeness of Hanks’ drawings imbues them with an endearing naïveté that echoes outsider art, and they wouldn’t be out of place alongside work by Howard Finster or Henry Darger.

Hanks populated his unusually-rendered world with fittingly unusual characters, the most notorious creation being Stardust the Super Wizard, “the most remarkable man that ever lived.” Stardust’s identity is inconsistent, alternating between omnipotent space alien and hyper-intelligent personification of a star (cue David Bowie song). His primary motivation in life is to make criminals and evil-doers suffer in the harshest, most depraved ways imaginable, in a spectacular indulgence of schadenfreude.

Stardust accomplishes this with the use of his amazing, other-worldly abilities, which are seemingly limitless and range from typical superhero fare (superhuman strength, flight, telepathy) to the frustratingly vague, like his “extra sight,” which is never elaborated upon, and no context for it is ever provided. This make-it-up-as-you-go-along approach is a hallmark of Hank’s work, an amusing quirk that lightens what are otherwise overwhelmingly dark stories.

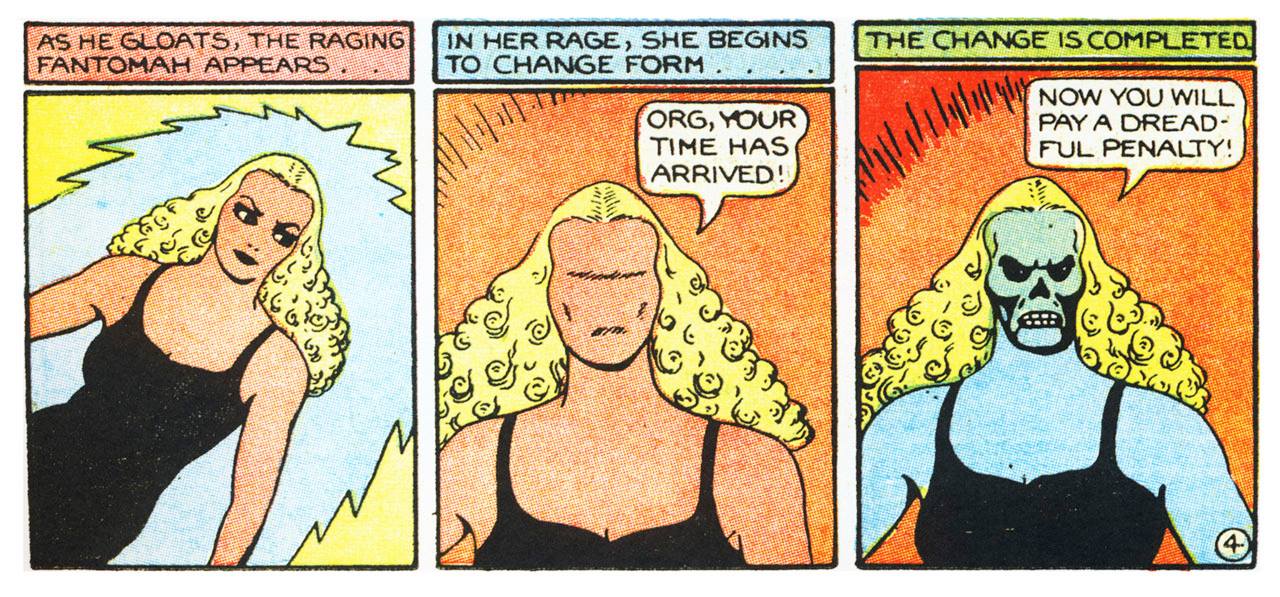

Hanks’ other major character is Fantomah, arguably the first female superhero, pre-dating Wonder Woman by a year and several months (first appearance: Jungle Comics #2, Feb. 1940). Fantomah, the supernatural “Mystery Woman of the Jungle,” serves as the noble protector of her realm, inflicting cruel retributive justice upon anyone who threatens the jungle’s peaceful existence. When she activates her powers, Fantomah’s face transmogrifies into a ghoulish, skull-like visage, her skin turns blue, and she shoots across the jungle to deliver swift justice. Like Stardust, Fantomah’s powers are many and are typically tailored to whatever the plot requires.

Considering both of Hanks’ best-known creations are identical in personality, motivation, and skill, elevated to idealized status and lacking any intended flaws, they’re classic self-insert material and perhaps something of a wish-fulfillment fantasy for Hanks, for whom stories of brutal retributive justice could be a kind of atonement for his own transgressions. Hanks frames each story as a morality tale, with every bizarre and inhumane punishment serving as a warning: this is what happens to bad men. The significance of these stories certainly deepens when considered in the context of what is known about Hanks the Man. It’s difficult not to read them as the product of a troubled mind tortured by guilt.

The extreme brand of justice meted out in lurid, gruesome detail in Hanks’ stories is, in a broad sense, in keeping with some of the central themes that emerged in the Golden Age, specifically the triumph of good over evil and the restoration of a moral order. However, few, if any, creators were as single-mindedly fixated on the sadism inherent in the deliverance of justice and revenge as Fletcher Hanks, and it’s this element of his work that, couched within the trippy, twisted landscape he renders on the page, cements it as a truly surreal reading experience.

Take Stardust’s encouner with the evil Destructo, the narrative trajectory of which is typical for a Hanks story: Destructo hatches a plot to suffocate all of America’s citizens with an oxygen-eliminating ray, and Stardust must put a stop to it. Stardust zaps Destructo with his “superiority beam,” shrinking Destructo’s head and immobilizing him. Destructo is terrified and begs for mercy, but as the wicked show no mercy, they shall receive none in return; Stardust tears off Destructo’s head and hurls it into space, where it bounces around aimlessly, until a giant, literal Head Hunter materializes out of the ether, grabs the head and absorbs it into his own body.

Like one hell of a bad trip, this twisted cycle plays out over and over in Hanks’ stories, in countless iterations distorted by his pen and ink. Innocents are needlessly tortured as collateral and villains are delivered a fate worse than death; they’re torn apart, hurled into the oxygenless expanse of space, frozen alive for eternity in floating ice prisons, tossed into a “pit of horrors,” or any number of other nightmarish scenarios, while the hero of choice takes perverse pleasure in condemning their adversaries to hellish suffering. When one particular schmuck fearfully asks what will happen to him next, Stardust emphatically replies: “I’ll show you the charred bodies of the millions of people you have killed!”

In one sense, it’s so outrageously over-the-top it’s hilarious, and the absurdity of these revenge/death tales is compounded by the freakishly wacky appearance of Hanks’ figures. Translated to another medium, the extremity of these scenes would be at home in an body horror or exploitation film. However, a tragic and troubling specter haunts this work, and even without knowing the sordid details of Hanks’ personal life, it is plainly the type of work that screams for armchair psychoanalysis.

Whichever way you look at it, Hanks’ work resonates, and his influence is present in comics today. Paul Karasik’s series of Hanks collections for Fantagraphics, I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets, You Shall Die By Your Own Evil Creation, and Turn Loose Our Death Rays and Kill Them All! are widely available. Fantomah appears in several issues of Hack/Slash from 2009-2011, and more recently, she’s the subject of a modern update from Chapterhouse, written by Ray Fawkes (Underwinter, Gotham By Midnight) with art by Soo Lee (Fight Like a Girl) and Djibril Morrisette-Phan (Glitterbomb).

So, was Fletcher Hanks a visionary as one of the first comic book auteurs to blaze his own unique path, or a doomed alcoholic who created as an act of catharsis? The answer probably falls somewhere in the middle. Due to the lack of information available giving insight into his creative process, or how he felt about his work, questions like these don’t have definitive answers. All we can do is speculate, continue to appreciate the work he’s left behind, and scratch our heads.

3 Comments